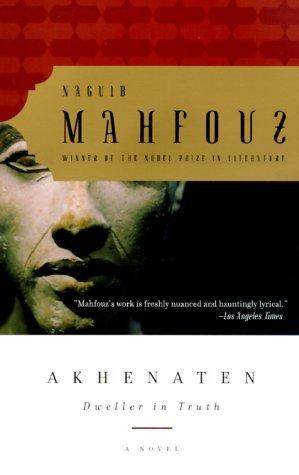

Naguib Mahfouz

Akhenaten: Dweller in Truth

English translation copyright © 1998 by The American University in Cairo Press

Originally published in Arabic as al-‘A’ish fi-l-haqiqa. Copyright © 1985 by Naguib Mahfouz.

The Beginning

It all began with a glance, a glance that grew into desire, as the ship pushed its way against the calm, strong current at the end of the flood season. The journey started from our city Sais, heading south toward Panopolis, where my sister had lived since her marriage. One late afternoon, our ship passed a strange city. It was bordered by the Nile to the west, and an imposing mountain to the east. Its buildings hinted of a past grandeur that had given way to a haunting evanescence. The roads were empty, the trees were leafless, the gates and windows closed like eyelids of the dead. A city devoid of life, inert, possessed by silence, shadowed by gloom and the spirit of death. I was dismayed at the sight of it, and I hurried to my father, who was seated, crowned with the dignity of old age, on a bench on the ship's deck.

“Father, what is wrong with this city?”

“Meriamun, this is the city of the heretic. The cursed and infidel city,” he replied calmly.

I looked again with increasing excitement, as the memories flowed.

“Does no one live there?”

“That woman, the heretic's wife, she still lives in her palace-or her prison I should say. And there must be a few guards.”

“Nefertiti,” I murmured to myself, remembering, and wondering how she had endured her isolation.

Visions from my boyhood at my father's palace in Sais kept coming to me, of the elders' fervent debates about the whirlwind that had devastated Egypt and the whole empire. They called it the war of the deities. I remembered the stories about the young pharaoh who had rejected his ancestors' heritage, challenged the priests, and defied destiny. I recalled those hushed voices, the talk of a new religion, and the people's bewilderment, unable to choose between their old faith and their loyalty to the pharaoh. People argued about unusual events, the terrible defeat of the empire, then the triumphs followed by grief.

So here was the city of wonders, possessed by the spirit of death. And there was its mistress, a solitary prisoner sipping bitterness. My heart beat fast, desperate to learn the whole story.

“You will never accuse me of meekness hereafter, Father, for I am swept by a sacred desire, strong as the northern winds, a desire to know the truth and record it, as you did in the prime of your youth.”

He glanced at me with weary eyes and said, “What is it that you want, Meriamun?”

“I want to learn everything about this city and its ruler. About the tragedy that ripped the country apart and laid waste the empire.”

“But you heard everything in the temple,” he replied.

“Father, the sage Qaqimna said, ‘Pass no judgment upon a matter until you have heard all testimonies.’”

“But the truth in this case is evident. Besides, Akhenaten, the heretic, is dead.”

“Most of his contemporaries are alive though,” I replied with growing excitement, “and they are your peers and friends. An introduction from you, Father, would help open doors and reveal secrets to me. Then I could see the many facets of truth before it perishes like this city.”

I insisted until finally he granted me his approval, possibly with concealed enthusiasm. For Father himself had a passion for knowledge and recording the truth, a fact that made our palace a gathering point for men of both worldly and religious affairs. Our palace was famous for its forums where stories were narrated and poetry recited, and for the great banquets of delicious duck and fine wines. Father was known among his friends as a man blessed with unique wisdom and abundant land.

He handed me some letters to deliver to the notable people who remembered that time: those who had participated closely, or from afar, and those who had experienced its bitterness as well as its sweetness.

“You have chosen your path, so walk it. May the gods protect you,” said Father. “Your forefathers sought war, politics, or trade, but you, Meriamun, you seek the truth instead, and one's cause ranks as high as the determination vested in it. Be careful not to provoke the powerful, or gloat over the misfortune of those who have fallen into oblivion. Be like history, impartial and open to every witness. Then deliver a truth that is free of bias for those who wish to contemplate it.”

I was happy to bid indolence farewell, and to set off along the path of history in search of truth, a path that has no beginning and no end, for it will always be extended by those who have a passion for eternal truth.

The High Priest of Amun

Thebes had returned to prosperity after its terrible desertion by the heretic. Once more it was the capital of the empire, its throne graced by the young pharaoh Tutankhamun. Men of peace and war returned to their positions, and the priests resumed their duties in the temples. Palaces were restored, gardens blossomed, and the temple of Amun regained its grandeur and stood proudly with its giant columns and flowering garden. The markets were filled with buyers, merchants, and goods, and the stream of wealth flowed continuously. The city was now a marvel of glory.

It was my first venture to Thebes. I was dazzled by its brilliant architecture and amazed by its vast population. I was overwhelmed by the sounds of the city and the sight of its roads, busy with carriages and carts. In comparison, my city Sais seemed like a small, quiet, obscure village.

I reached the temple of Amun at the appointed time. A servant ushered me through the hall of grand columns and into a lateral corridor leading to the room where the high priest awaited me. I saw him in the center of the room, seated on a chair of ebony with armrests of pure gold. He was an elderly man with a shaved head, and was dressed in a long flowing skirt, with a white sash wrapped around his chest and shoulders. Despite his advanced age he was a man of vigor and had a confident heart. He honored my father at the mention of his name and praised his loyalty.

“Those times of adversity helped us recognize men of good will like your father,” he said. Then he murmured a few compliments regarding my endeavor and continued, “We have destroyed the walls with all the false inscriptions they bore. The truth, however, must be recorded.” He leaned his head forward in gratitude. “Now Amun sits prosperously on his throne and in the holy of holies, master of all deities, protecting Egypt and fighting off its enemies. His priests, too, have regained their precedence. Amun liberated our valley by the power he vested in Ahmose, and extended our empire in every direction by the power he vested in Tuthmosis III. For he grants victory to whom he wishes, and humbles those who betray him.”

I knelt in reverence until he called on me to rise and be seated on a chair before him. I listened carefully as the high priest spoke.

It is a very sad story, Meriamun, though in the beginning it seemed merely an innocent whisper. It started with the Great Queen Tiye, the heretic's mother and wife of the Great Pharaoh, Amenhotep III. She came from a common Nubian family, with not a drop of royal blood in her veins. Yet she was shrewd and powerful, as though she had four eyes and could see in all directions at once. She was intent on maintaining friendly relations with us. I shall never forget her words on the day of the Nile Festival: “You priests of Amun are the fortune and blessing of