apart from our own, as an expression of the will to survive of the species. For the ancients, too, the sexual urge was an expression of a will beyond the individual. They saw sexuality impelling us towards the great moments of our lives, because they saw how sex controls who we are born to, as well as determining the people we are attracted to.

A man in the ancient world might see a woman he desired and be overcome by a quite frightening, overwhelming desire. He would know that the rest of life would be shaped by her response. He would also know that the roots of his desire lay very, very deep, having their origins long before his present lifetime. He would know that the sexual desire that drove him towards that woman was not merely biological — as in the modern account — but had other dimensions, spiritual and sacred. If the planet of love had been steering them towards this meeting, then so, too, had the other great gods of the sky been preparing this experience for them over many, many millennia and through many incarnations.

Today we know that when we look at a distant star we are seeing something that happened a very long time ago, because of the time it has taken for the light from that star to reach the earth. The ancients knew another truth, which is that when they contemplated their own will, they were also looking at something which they had formed long before they were born. The ancients knew that every time they felt themselves merging with another human being in the sexual act, the flight of whole constellations was involved. They knew, too, that

When we make love we are interreacting with great cosmic powers, and if we choose to do so

THERE IS ONE FURTHER TWIST TO THE STORY of Osiris, a dark shadow to an already dark story. We saw that Isis had a sister, Nepthys, and there was a suggestion of sexual impropriety with Osiris, some sexual fall from grace perhaps. But later Nepthys used her magic powers to help Isis in her search for the body parts of Osiris and helped, too, to bind them together again.

Nepthys, then, is a figure representing some dark form of wisdom, fallen but capable of redemption.

In Christian mythology this same figure, this same spiritual impulse, reappears as Mary Magdalene. We have been following the history of the Fall. We have seen that the Fall was not the fall of human spirits into a pre-existing material world — it is a very easy and common mistake to imagine it like this — but a Fall in which human bodies became denser as the material world became denser.

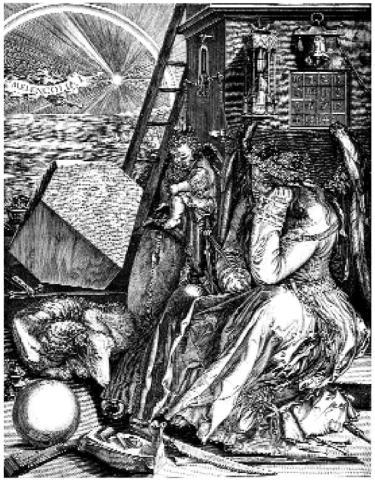

We live in a Fallen world. Just as myriad spirits help us to grow and evolve, so too others, just as numerous, work to destroy both us and the very fabric of our world. In Christian mythology — and in the secret doctrine of the Church — the earth suffered and was punished for having fallen by having her own spirit imprisoned deep in the underworld inside her. Sometimes called Sophia, notably in the Christian tradition, this wisdom is only reached when we travel down through the dark and demonic places of the earth and also of ourselves. It is because of Nepthys — because of Sophia — that we all have need to touch rock bottom, to experience the worst that life has to offer, to wrestle with our demons, to test our intellect to its limits and journey to the other side of madness.

We know from Plutarch that in antiquity Isis was identified with Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom. Athena had a half-sister, a dark-skinned girl called Pallas, whom she loved more than anyone. Carefree, they used to play on the plains of Anatolia, running games, wrestling and mock fights with spears and shields. But one day Athena was distracted. She slipped and accidentally speared Pallas to death.

From then on she called herself Pallas Athena, to acknowledge the dark side of herself, just as in a sense Nepthys represents the dark side of Isis. She also carved a statue of Pallas out of black wood to memorialize her.

This statue, called the Palladium, carved by the hand of a goddess and washed by her tears was revered as an object of world-changing power in antiquity. When the people of Anatolia kept it in their capital, Troy was the greatest city in the world. The Greeks wanted to know what the Trojans knew. When they carried it off triumphantly, the leadership of world civilization passed to them. It was later buried beneath Rome in all its glory, until the Emperor Constantine moved it to Constantinople, when it became the centre of world spirituality. Today it is said to be hidden somewhere in Eastern Europe, which is why in recent times, the great powers, the Freemasonic ones, have sought to control this region.

The cult of Nepthys together with its Greek and Christian equivalents, forms one of the darkest and most powerful streams in occultism. Great forces like these shape the history of the world even now.

7. THE AGE OF DEMI-GODS AND HEROES

WHEN HERODOTUS WAS PUZZLING OVER the strange wooden statues of the kings who had reigned before any human king, the Egyptian priests told him that no one could understand this history without knowing about ‘the three dynasties’.

If Herodotus had been an initiate of the Mystery schools, he would have understood that the three dynasties were, first, the oldest generation of creator gods — Saturn, Rhea, Uranos — the second generation made up of Zeus, his siblings and their children, such as Apollo and Athena — and lastly the generation of demi-gods and heroes. This last generation is the subject of this chapter.

ALL THE WHILE MATTER WAS GROWING denser, and because matter and spirit are inimical, the gods became less and less a constant presence. The higher, the more ineffable, the god, the harder it became to squeeze down into the tightening net of physical necessity that covered the earth. Great gods such as Zeus or Pallas Athena seemed to make their presence felt and intervene directly in human affairs only at times of crisis.

In the Mystery schools it was taught that a decisive change in this direction came about in 13,000 BC. From then on the higher gods would find it difficult to descend further than the moon. Their visits to the surface of the earth became infrequent and fleeting. It was believed that on these visits they accidentally left behind the strange and unearthly mistletoe, a plant which cannot grow in the soil of the earth, but which grew naturally on the moon.

Without the presence of the greater gods to keep them down, the crab-like progeny of Saturn that had been imprisoned in underground caves began to creep up into the daylight again, infesting the surface of the earth and preying on humankind. Sea monsters also leapt on to the shore to drag off members of the tribe who had strayed too close. Giants carried off cattle and sometimes preyed on human flesh, too.

Full-scale wars took place between humans and armies of other creatures, stragglers from the previous epoch. The war between the Lapiths — a tribe of Neolithic flint-knappers — and the Centaurs is recorded on the Parthenon frieze. The Centaurs had been invited to the wedding of the leader of the Lapiths, but were inflamed by the sight of the white, hairless bodies of the Lapith women. They dragged off the bride and raped her — and her bridesmaids and page boys, too. In the ensuing fight a Lapith king was killed, and so began a feud that lasted for