get all the information I could out of him.

After all, there wasn’t much he could tell me. All the normal sources of inquiry had drawn a blank. The dead man simply wasn’t known to the police.

‘This does not mean he is not a criminal,’ Feder explained, rubbing his thick grey eyebrows. ‘It only means that he is not known to us or to Interpol. He may have been arrested in some other country.’

‘Have you checked in the States?’ I asked, leaning back in my chair and taking a deep breath.

‘What?’ Feder’s eyes moved reluctantly back to my face. ‘Ah —

‘The museum authorities are rather concerned.’

‘Yes, so I understand. And yet, Fraulein Doktor, is there really any cause for suspicion? Like all police departments these days, we are badly overworked. We have too much to do investigating crimes that

‘Oh, I don’t intend to pursue criminals into dark alleys, or anything like that,’ I said. We both laughed gaily at the very idea. Herr Feder had big, white, square teeth. ‘But,’ I continued, ‘I am curious about the case; I was about to take leave anyway, and Herr Professor Schmidt suggested I might pursue certain leads of our own, just to see what I could find out. I wonder . . . I guess I had better see the corpse.’

I don’t know why I made that suggestion. I’m not squeamish, but I’m not ghoulish, either. It was just that I couldn’t think of anything else to do. I had no other lead.

I regretted my impulse when I stood in the neat, white antiseptic room that houses the morgue of Munich. It was the smell that got me: the stench of carbolic, which doesn’t quite conceal another, more suggestive, odour. When they turned the sheet back and I saw the still, dead face, I didn’t feel too good. Suggestion – the reminder of my own mortality. There was nothing particularly gruesome about the face itself.

It was that of a man in middle life, though the lines were smoothed out and negated by death. He had heavy black brows and thick, greying black hair; his complexion was tanned or naturally swarthy. The lips were unusually wide and full. The eyes were closed.

‘Thank you,’ I muttered, turning away. When we got back to his office, Feder offered me a little sip of brandy. I hadn’t been that upset, but I didn’t like to shatter his faith in female gentleness. Besides, I like brandy.

‘He looks like a Latin,’ I said, sipping. It was good stuff.

‘Yes, you are right.’ Feder leaned back in his chair, his glass held lightly between unexpectedly delicate fingers. ‘Spanish or Italian, perhaps. It is unfortunate that we found no identification.’

‘That seems suspicious.’

‘Perhaps not. The man was in the alley for hours, no one knows how long. It is possible that some casual thief robbed him. If he carried a wallet or bag, it would have been stolen for the money it contained. His papers, if any, would have been in that wallet. And a valid passport is always useful to the criminal element.’

‘Yes, of course,’ I agreed. ‘A thief would have overlooked the jewel, since it was sewn into his clothing.’

‘So we think. There were a few odds and ends in his pockets, the sort of thing a thief would not bother with. Handkerchief, keys – ’

‘Keys? Keys to what?’

Feder produced a positively Gallic shrug.

‘But who can tell, Fraulein Doktor? They were not keys to an automobile. If he had an apartment, the good God alone knows where it might be. We inquired among the hotels of the city, but have had no luck. It is of course possible that he only arrived in Munich yesterday and had not registered at a hotel. Would you care to see the contents of his pockets?’

‘I suppose I should,’ I said glumly.

I wasn’t expecting anything. I just said that because I felt I shouldn’t overlook any possible clue. Little did I know that in that pitiful collection lay the key that was to unlock the case.

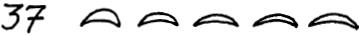

It was a folded piece of paper. There were several other scraps like it, receipts from unidentified shops for small sums, none over ten marks. This particular scrap was not a receipt, just a page torn out of a cheap notebook. On it was written the number thirty-seven – the seven had the crossbar that is used by Europeans for writing that number, in order to distinguish it from their numeral one – and a curious little group of signs that resembled fingernail clippings. They looked like this:

I sat staring at these enigmatic hieroglyphs until Herr Feeder’s voice interrupted my futile theorizing.

‘A puzzle of some sort,’ he said negligently. ‘I see no meaning in it. After all, the cryptic clue only occurs in

‘How true,’ I said.

Herr Feder laughed. ‘It is, perhaps, the address of his manicurist.’

‘Were his nails manicured?’ I asked eagerly.

‘No, not at all.’ Herr Feder looked at me reproachfully. ‘I made a little joke, Fraulein Doktor.’

‘Oh.’ I giggled. ‘The address of his manicurist . . . Very witty, Herr Feder.’

I shouldn’t have encouraged him. He asked me to dinner, and when I said I was busy, to lunch next day. So I told him I was leaving town. Usually I deal with such matters more subtly, but I didn’t want to discourage him completely; who knows, I might need help from him if the case developed unexpected twists. Although at that point I didn’t even have a case, much less a twist.

It was a gorgeous spring day, a little cool, but bright and blue-skied, with fat white clouds that echoed the shapes of Munich’s onion-domed church spires. I should have gone back to work – I had a number of odds and ends to clear up if I was going to play Sherlock – but there was no point in clearing them up if I didn’t know where I was going. And I couldn’t face Professor Schmidt. He would expect me to have deduced all kinds of brilliant things from my visit to the police.

I wandered towards the

I passed through the Viktualenmarkt, with its booths of fresh fruits and vegetables and its glorious flower stalls. They were masses of flaming colour that morning, all the spring flowers – yellow bunches of daffodils, great armfuls of lilac, fat blue and pink hyacinths perfuming the air. I ended up on Kaufingerstrasse, which was a favourite haunt of mine, because I adore window-shopping. It was just about the only kind of shopping I could afford. Some of the most delectable windows were those of the shops that sold the lovely peasant costumes of southern Germany and Austria. People still wear them, even in sophisticated Munich – loden cloaks of green or creamy-white wool, banded in red, with big silver buttons; blouses and aprons trimmed with handmade lace; and, of course, dirndls. They differ in style according to the area where they originated: the sexy Salzburger dirndl, with its lowcut bodice, artfully designed to make the most of a girl’s secondary sex characteristics; the Tegernsee type, which has a separate skirt and jacket, the latter lengthened behind into a stiff pleated peplum. I love those brilliant costumes, of bright cotton print or embroidered velvet; but I am not the dirndl type. However, I had my eye on an ivory wool cape with buttons made out of old silver coins, so I stopped by the shop to see if by any chance they were having a sale. They weren’t. I turned away, and then something across the street caught my eye.

It was only an advertising sign for Lufthansa airlines. ‘Rome!’ it exclaimed, above a huge photograph of the Spanish Steps lined with baskets of pink and white azaleas. ‘See Rome and live! Six flights daily.’

All the pieces came together then, the way they do sometimes when you leave them alone and let them simmer. The swarthy skin and Latin look of the dead man; Herr Feder’s joking suggestion that the cryptogram represented an address; the atmosphere of antiquities, treasure, and jewels that coloured the whole affair.

I had been thinking vaguely of going to Rome on my holiday, and wondering where I was going to get the