10. Easy-to-name and difficult-to-name colors in Chinese.

11

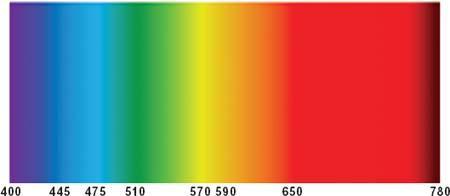

11. The visible spectrum, with wavelengths marked in nanometers (millionths of a millimeter).

12

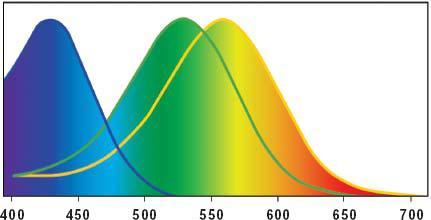

12. The normalized sensitivity of the short-wave, middle-wave, and long-wave cones as a function of wavelength.

[1] Most Bible translations smooth over oddities such as “green gold” (Psalms 68:13) and render the adjective as “yellow.” But the etymology of the word derives from plants and leaves, just like Homer’s

[2] Geiger seems somewhat confused about whether black and white should be considered real colors and about how they relate to the more general concepts of dark and bright. In this one respect, his analysis is a step backward from Gladstone’s masterly account of the primacy of dark and bright in Homer’s language.

[3] In 2007, three researchers, Terry Regier, Naveen Khetarpal, and Paul Kay (same one), made a tentative suggestion for explaining the nature of these anatomical constraints. They started from the idea that a concept is “natural” if it groups together things that appear similar to us, and they argued that a natural division of the color space is one in which the shades within each color category are as similar to one another as they can be and as dissimilar as possible from shades in other categories. Or put more accurately, a natural division maximizes the perceived similarity between shades inside each concept and minimizes the similarity between shades that belong to different concepts. One might have imagined that any division of the spectrum into continuous segments would be equally natural in this respect, because neighboring shades always appear similar. But in practice, the accidents of our anatomy make our color space asymmetric, because our sensitivity to light is greater in certain wavelengths than in others. (More details can be found in the appendix.) Because of such non-uniformities, some divisions of the color space are better than others in increasing the similarity within concepts and decreasing it across concepts.

[4] In many languages the name of the color red actually derives from the word “blood.” And as it happens, this linguistic connection has exercised the minds of generations of biblical exegetes, because it bears on the name of none other than the father of mankind. According to the biblical etymology, Adam owes his name to the red tilled soil,

[5] There has been a lot of brouhaha in the last few years about Piraha, a language from the Brazilian Amazon, and its alleged lack of subordination. But a few Piraha subordinate clauses have recently managed to escape from the jungle and telegraph reliable linguists to say that reports of their death have been greatly exaggerated. (See notes for more information.)

[6] Gender markers are the elements that indicate the gender of a noun. Sometimes, the gender markers can be suffixes on the noun itself, as in Italian