Poor communications had come into play just minutes into the assault, when one side ended up literally shooting at the other. Howe and his Commando team had been on the roof of the target house, rounding up Somalian prisoners, when they fired at a Somali on a nearby rooftop. They were instantly peppered with return fire—not just from the Somali, but from a Ranger blocking position on the ground. A Ranger had evidently seen shooting from the roof and had fired away without checking it out.

The Commando men weren’t hit, but Howe was furious. He got on the radio and told the mission commander to order that idiot Steele to have his men stop shooting at their own people!

Howe’s team, with several Rangers in tow, was the first to round the corner on Freedom Road, a wide dirt street that stretched north to the crash site. The road sloped slightly downhill to where the other Rangers and rescue team had established a perimeter two blocks away. The team had just rounded the corner when an RPG hit the wall close by. It knocked some of Howe’s team off their feet. Howe felt the wallop of pressure in his ears and chest and dropped to one knee. One of his men had been hit with a small piece of shrapnel to his left side.

They had to find cover to treat the wounded man. Howe abruptly kicked in the door to a one-room house and barged in with his weapon ready. Less-experienced soldiers still felt normal civilian inhibitions about doing things like kicking in doors, but Howe and his men moved as if they owned the world. Every house was their house. If they needed shelter, they kicked in a door. Anyone who threatened them would be shot dead.

The house was empty. Howe and his men caught their breath and reloaded. Running under the weight of their gear was exhausting, and the body armor was like wearing a wet suit. They were sweating profusely and breathing heavily. Howe drew his knife and cut away the back of the wounded man’s uniform to check the shrapnel wound. There was a small hole in the man’s back, with a swollen, bruised ring around it. There was almost no blood. The swelling had closed the hole.

“You’re good to go,” Howe told him.

Behind them, Sgt. Goodale moved with a group of Rangers led by First Lt. Larry Perino. Goodale had just turned to squeeze off a round when he felt a stabbing pain. His right leg abruptly seized up and he fell over backward, right into Perino.

Perino heard Goodale say, “Ow!”

A bullet had entered his right thigh and passed through him, leaving a gaping exit wound on his right buttock. Goodale thought at that instant about a soldier who supposedly had lost an arm and a leg after a LAW—a light antitank weapon—he was carrying exploded when a round hit it. Goodale was carrying a LAW! He flailed wildly, trying to get the weapon off his shoulder.

Perino couldn’t tell what Goodale was doing.

“Where are you hit?” he asked.

“Right in the ass.”

Goodale dropped the LAW.

Perino left Goodale with a Commando medic and moved on across the intersection. Goodale lay back on the dirt as the medic looked him over.

“You got tagged. You’re all right, though. No problem,” the medic said.

Goodale had the same feeling he used to get in a football game when he got injured. They carried you off the field and you were done. He yanked off his helmet, then saw an RPG fly past no more than six feet in front of him and explode with a stupendous wallop about 20 feet away. He put his helmet back on. The game was most definitely not over.

“We need to get off this street,” the medic said.

He dragged Goodale into a small courtyard, and several boys hopped in with them. Goodale asked one of them to help him reach his canteen, which the medic had taken off to work on him. The boy fished it out of Goodale’s butt pack and discovered a bullet hole clean through it from the same round that had passed through his body. Goodale decided he would keep the canteen as a souvenir.

Capt. Steele and a large contingent of Rangers were the last to make the turn onto Freedom Road. Steele got a radio call from Perino.

“Captain, I’ve got another man hit.”

“Pick him up and keep moving,” Steele said.

The captain was struggling to maintain a semblance of order. He needed to consolidate his Rangers into a single force. Time was essential. Steele had been told the ground convoy would probably reach the crash site before he and his men did. He did not yet know the convoy was lost and being riddled with gunfire. Assuming that the convoy would arrive at any minute, Steele was concerned. He had about 60 young Rangers to account for— and only a vague idea where they all were. He was pondering all this while on his belly in the dirt, his broad face nearly in the sand.

The captain and Sgt. Chris Atwater, Steele’s radio operator, were massive men, and they were both trying to take cover behind a tree trunk about a foot wide. In front of them, the last team of boys was moving into the intersection.

Just then one of the boys, Sgt. Fillmore, went limp. His little hockey helmet jerked up and blood came spouting out of his head. He hit the ground, dead.

The boy behind Fillmore grabbed him to pull him back into a narrow alley a few steps away. He, too, was hit—in the neck. A third team member helped the wounded soldier pull Fillmore into the alley.

For the first time that day, Steele felt the gravity of their predicament hit fully home.

CHAPTER 21

A Shared Quest: Punish the Invaders

WHEN THE AMERICAN helicopters opened fire on Kassim Sheik Mohamoud’s garage in southern Mogadishu, two of his employees were killed.

Ismail Ahmed was a 30-year-old mechanic, and Ahmad Sheik was a 40-year-old accountant and one of Kassim’s right-hand men. Somalian militiamen were hiding inside the garage compound, so Kassim knew they might be bombed. When the shooting started, the beefy businessman had quickly run to the Digfer Hospital to hide. He figured the Americans would not shoot at a hospital.

He stayed there two hours. It sounded as if the whole city were exploding with gunfire. As dusk approached his men brought him news of the two deaths, and because their Islamic faith called for them to bury the dead before sundown, Kassim left the hospital and returned to his garage to lead a burial detail.

He set off for Trabuna Cemetery with three of his men and the bodies of Ismail Ahmad and Ahmad Sheik.

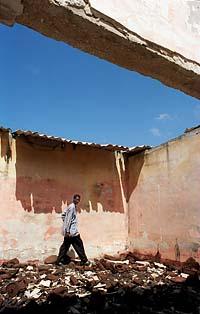

Mogadishu was in turmoil. Buses had stopped running, and all of the major streets were blocked. American helicopters were shooting at anything that moved in the southern portion of the city, so many of the wounded could not be taken to hospitals. Wails of grief and anger rose from many homes, and angry crowds had formed in a broad ring around Cliff Wolcott’s Blackhawk, the first of two helicopters that crashed. People swarmed through the streets, seeking vengeance. They wanted to punish the invaders.

Hours earlier, Ali Hassan Mohamed had run to the front door of his family’s hamburger and candy shop when the helicopters came down and the shooting started. He was a student, a tall and slender teenager with prominent cheekbones and a sparse goatee. He studied English and business in the mornings, and manned the store in the afternoons just up from the Olympic Hotel.

The front door was diagonal across Hawlwadig Road from the house of Mohamed Hassan Awale, which was the target building where the Rangers were attacking. Peering out his doorway, Ali saw Rangers coming down on ropes. They were big men who wore body armor and strapped their weapons to their chests and painted their faces black and green to look more fierce. They were shooting as soon as they hit the ground. There were also Somalis shooting at them.

Then a helicopter had come low and blasted streams of fire from a gun on its side. Ali’s youngest brother,