MICHAEL DURANT heard birds singing and the voices of children at play. He had no idea where he was in Mogadishu, but the sounds and the sunlight beaming through holes in the concrete walls seemed at stark odds with everything that had happened hours before.

The injured, captive Blackhawk pilot was flat on his back on a cool tile floor in a small octagonal room with no windows. Air, sunlight and sounds filtered in through crosses cut into the concrete of the walls. There was a dusty odor. He smelled of blood and powder and sweat. The room had no furniture and only one door, which was closed.

It was Monday, Oct. 4, the morning of a day Durant thought he would never see. He had not slept. The previous evening, he had been attacked and carried off by angry Somalis who had overrun his downed helicopter crew and two Commando sergeants who had fought to protect them. The others were all dead, but Durant did not know this.

His right leg ached where the femur was broken, and he could feel the ooze of blood inside his pants where the bone had poked through his flesh in the manhandling he’d endured. It did not hurt that badly. He didn’t know if that was good or bad. He was still alive, so clearly the severed bone had not punctured an artery. His back was what really bothered him. He figured he’d crushed a vertebra in the crash.

The Somalis had bound him with a metal dog chain. They had wrapped it around his hands, which were pulled together on his stomach. During the long night he had worked one hand free. He was sweating so that when he relaxed his hand it slid easily from the chain. It had given him his first sense of triumph. He had fought back in some small way. He could wipe the dirt from his nose and eyes and straighten his broken leg somewhat and get a little more comfortable. Then he wrapped his hand back into the chain so his captors wouldn’t know.

The birdsong made him think he was in a garden, and that this strange room was some kind of garden house. The children’s voices made him think of an orphanage. He knew there was one in northern Mogadishu.

Durant had passed out when he was carried off. He’d felt himself leaving his body, watching the scene from outside himself, and it had calmed him briefly. But the feeling hadn’t lasted long. He’d been thrown roughly into the back of a flatbed truck with a rag tied around his head. He had been driven around for a while. The truck would go and then stop, go and then stop. He guessed it was about three hours after the crash when they’d brought him to this place, removed the rag, and bound him with the chain.

The pilot had no way of knowing, but he had been kidnapped from Yousuf Dahir Mo’Alim, the neighborhood militia leader who had spared him from the attacking crowd. Mo’Alim and his men had been trying to take Durant back to their village, where they intended to contact leaders of his clan, the Habr Gidr. Durant couldn’t walk, so they were carrying him when they were intercepted by a Land Cruiser with a big gun mounted on the back. The men in the vehicle were freelance street fighters, bandits not aligned with any clan. They considered the injured pilot not a war prisoner to be traded for captured Habr Gidr leaders, but a hostage. They knew somebody would pay to get him back.

Mo’Alim’s men were outnumbered and outgunned, so they reluctantly turned Durant over. This was the way things were in Mogadishu. Whoever had the bigger guns prevailed. If the Habr Gidr leader, Mohamed Farrah Aidid, wanted the pilot back, he would have to pay for him.

The kidnappers had placed Durant in this room, and chained him. During the long night the pilot heard the roaring guns of the giant rescue column blazing its way into the city. At one point he heard several armored personnel carriers roll right past outside. He heard shooting and thought he was about to be rescued, or killed. There was a furious gunfight outside.

He could hear the low, pounding sound of a Mark 19 and the explosions of what sounded like TOW missiles. He had never been on the receiving end of a barrage, and he was shaken by how powerful and frightening it was. The explosions came closer. The Somalis holding him grew more and more agitated. He heard them shouting, and several times they barged in to threaten him. One of the men spoke some English. He said, “You kill Somalis. You die Somalia, Ranger.” Durant couldn’t understand the rest of their words, but he gathered they intended to shoot him before letting the approaching Americans take him back.

His captors were all young men. Their weapons were rusted and poorly maintained. He listened to the pitched fighting with terror and hope. Then the sounds marched on and faded away. He found himself, despite the danger, feeling abject at their departure. They had been so close!

Soon dawn came. Durant was still frightened and uncomfortable and very thirsty, but the sunlight and the birds and children calmed him. He felt safer than at any moment since the crowd had closed on him.

Then a gun barrel poked around the door. Durant caught the motion out of the corner of his eye and turned his head just as the barrel flamed and the room rang with the sound of a shot. He felt the impact on his left shoulder and his left leg. Eyeing his shoulder he saw the back end of a round protruding from his skin. It evidently had hit the floor first and had ricocheted into him without fully penetrating. A bit of shrapnel had entered his leg.

He slid his hand free of the chain and tried to wrench the bullet from his shoulder. It was an automatic move, a reflex, but when his fingers touched the round they sizzled and he winced with pain. The bullet was still hot. It had burned his fingertips.

He thought, lesson learned: Wait until it cools off.

WORD SPREAD QUICKLY through the hangar back at the base early the next morning, Tuesday, Oct. 5. There was something on the TV, on CNN, they had to see. Something horrible.

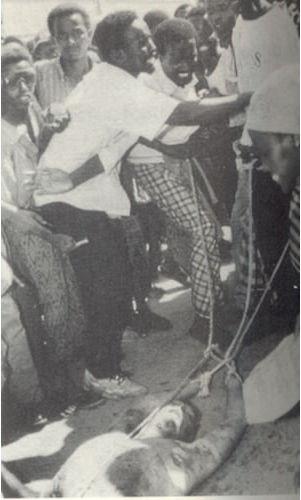

The aching and tired Rangers and Commando soldiers, many bandaged and bruised, watched the screen with disgust and anger. The pictures showed jubilant Somalis bouncing on the rotor blades of Super 64, Durant’s helicopter, and then showed a thing almost too wounding and terrible to watch.

They had bodies. Bodies of these men’s brothers, crew members from the helicopter or Commando soldiers, it was hard to tell from the angles and distances of the camera shots. They were dragging a body through the street at the end of a rope, kicking and poking at the lifeless form. It was ugly and savage, and the men went back out to the hangar and cleaned their weapons and waited for orders that would send them back out.

Commando Sgt. Paul Howe was ready. If he was going back out, he was going to kill as many Somalis as he could. He’d had enough. No more rules of engagement, no more toeing some abstract moral line. He was going to cut a gruesome path through these people.

BASHIR HAJI YUSUF was disgusted and ashamed by what he saw. The bearded lawyer had come down to the Bakara Market after the shooting to witness and photograph the aftermath. Bodies had been pulled off the streets, but he saw dead donkeys on the road, bloated and stiff. A great deal of damage had been done to buildings around the crash site nearest the Olympic Hotel.

He was snapping pictures of the helicopter wreckage when he heard the sounds of an excited crowd and ran to it. The Somalis had a dead American soldier draped across a wheelbarrow.

Bashir stayed on the fringes of the angry crowd. He snapped a few pictures. Then the people took the body of the soldier from the wheelbarrow and began dragging it in the dirt. Women were screaming curses, and the men were shouting and laughing.

The lawyer wanted to stop it. He wanted to step up to the men with the ropes and remind them that the Koran teaches respect for the dead. But he was afraid for himself so he stayed back. These people were wild with anger and revenge. It was a festival of blood. He followed the crowd for a few blocks, then slipped away and went home.

A contingent of Saudi Arabian soldiers in U.N. vehicles encountered the crowd pulling the dead American by the K-4 Circle. The crowd had grown quite large.

“What are you doing?” asked one of the Saudi soldiers, clearly shocked.