lot of openended questions, often following with 'Why?,' giving people an opportunity to reveal themselves, to brag or bullshit or show signs of anxiety.

Coburn wondered whether Simons would flank any of them.

At one point he said: 'Who is prepared to die doing this?'

Nobody said a word.

'Good,' said Simons. 'I wouldn't take anyone who was planning on dying.'

The discussion went on for hours. Simons broke it up soon after midnight. It was clear by then that they did not know enough about the jail to begin planning the rescue. Coburn was deputized to find out more overnight: he would make some phone calls to Tehran.

Simons said: 'Can you ask people about the jail without letting them know why you want the information?'

'I'll be discreet,' Coburn said.

Simons turned to Merv Stauffer. 'We'll need a secure place for us all to meet. Somewhere that isn't connected with EDS.'

'What about the hotel?'

'The walls are thin.'

Stauffer considered for a moment. 'Ross has a little house at Lake Grapevine, out toward DFW Airport. There won't be anyone out there swimming or fishing in this weather, that's for sure.'

Simons looked dubious.

Stauffer said: 'Why don't I drive you out there in the morning so you can look it over?'

'Okay.' Simons stood up. 'We've done all we can at this point in the game.'

They began to drift out.

As they were leaving, Simons asked Davis for a word in private.

'You ain't so goddam tough, Davis.'

Ron Davis stared at Simons in surprise.

'What makes you think you're a tough guy?' Simons said.

Davis was floored. All evening Simons had been polite, reasonable, quiet-spoken. Now he was making like he wanted to fight. What was happening?

Davis thought of his martial arts expertise, and of the three muggers he had disposed of in Tehran, but he said: 'I don't consider myself a tough guy.'

Simons acted as if he had not heard. 'Against a pistol your karate is no bloody good whatsoever.'

'I guess not--'

'This team does not need any ba-ad black bastards spoiling for a fight.'

Davis began to see what this was all about. Keep cool, he told himself. 'I did not volunteer for this because I want to fight people, Colonel, I--'

'Then why

'Because I know Paul and Bill and their wives and children and I want to help.'

Simons nodded dismissively. 'I'll see you tomorrow.'

Davis wondered whether that meant he had passed the test.

In the afternoon on the next day, January 3, 1979, they all met at Perot's weekend house on the shore of Lake Grapevine.

The two or three other houses nearby appeared empty, as Merv Stauffer had predicted. Perot's house was screened by several acres of rough woodland, and had lawns running down to the water's edge. It was a compact woodframe building, quite small--the garage for Perot's speedboats was bigger than the house.

The door was locked and nobody had thought to bring the keys. Schwebach picked a window lock and let them in.

There was a living room, a couple of bedrooms, a kitchen, and a bathroom. The place was cheerfully decorated in blue and white, with inexpensive furniture.

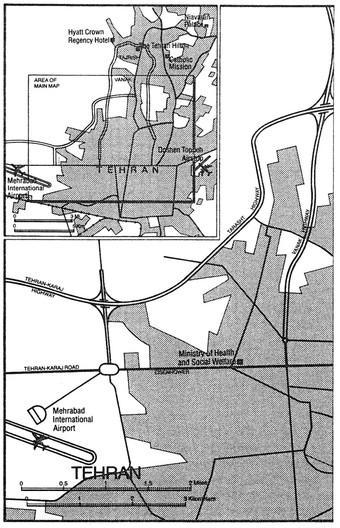

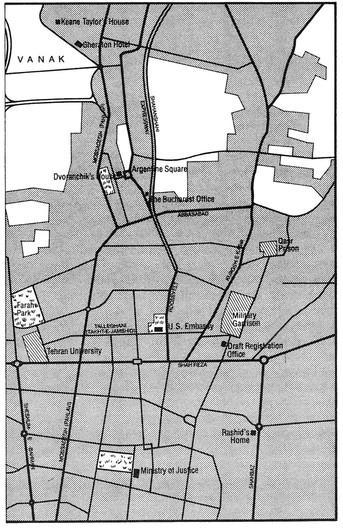

The men sat around the living room with their maps and easel pads and magic markers and cigarettes. Coburn reported. Overnight he had spoken to Majid and two or three other people in Tehran. It had been difficult, trying to get detailed information about the jail while pretending to be only mildly curious, but he thought he had succeeded.

The jail was part of the Ministry of Justice complex, which occupied a whole city block, he had learned. The jail entrance was at the rear of the block. Next to the entrance was a courtyard, separated from the street only by a twelve-foot-high fence of iron pilings. This courtyard was the prisoners' exercise area. Clearly it was also the prison's weak point.

Simons agreed.

All they had to do, then, was wait for an exercise period, get over the fence, grab Paul and Bill, bring them back over the fence, and get out of Iran.

They got down to details.

How would they get over the fence? Would they use ladders, or climb on each other's shoulders?

They would arrive in a van, they decided, and use its roof as a step. Traveling in a van rather than a car had another advantage: nobody would be able to see inside while they were driving to--and, more importantly, away from--the jail.

Joe Poche was nominated driver because he knew the streets of Tehran best.

How would they deal with the prison guards? They did not want to kill anyone. They had no quarrel with the Iranian man in the street, or with the guards: it was not the fault of those people that Paul and Bill were unjustly imprisoned. Furthermore, if there was any killing, the subsequent hue and cry would be worse, making escape from Iran more hazardous.

But the prison guards would not hesitate to shoot

The best defense, Simons said, was a combination of surprise, shock, and speed.

They would have the advantage of surprise. For a few seconds the prison guards would not understand what was happening.

Then the rescuers would have to do something to make the guards take cover. Shotgun fire would be best. A shotgun would make a big flash and a lot of noise, especially in a city street: the shock would cause the guards to react defensively instead of attacking the rescuers. That would give them a few more seconds.

With speed, those seconds might be enough.

And then they might not.

The room filled with tobacco smoke as the plan took shape. Simons sat there, chain-smoking his little cigars, listening, asking questions, guiding the discussion. This was a very democratic army, Coburn thought. As they got involved in the plan, his friends were forgetting about their wives and children, their mortgages, their lawn mowers and station wagons; forgetting, too, how outrageous was the very idea of their snatching prisoners out of a jail. Davis stopped clowning; Sculley no longer seemed boyish but became very cold and calculating; Poche wanted to talk everything to death, as usual; Boulware was skeptical, as usual.

Afternoon wore into evening. They decided the van would pull onto the sidewalk beside the iron railings. This sort of parking would not be in the least remarkable in Tehran, they told Simons. Simons would be sitting in the front seat, beside Poche, with a shotgun beneath his coat. He would jump out and stand in front of the van. The back door of the van would open and Ralph Boulware would get out, also with a shotgun under his coat.

So far, nothing out of the ordinary would appear to have happened.

With Simons and Boulware ready to give covering fire, Ron Davis would get out of the van, climb on the roof, step from the roof to the top of the fence, then jump down into the courtyard. Davis was chosen for this role because he was the youngest and fittest, and the jump--a twelve-foot drop--would be hard to take.