might be changed, the bail might be reduced, and Chiapparone and Gaylord might even be released on their personal guarantees.'

Nothing could be plainer than that, Howell thought. EDS had better go see the Minister of Health.

Since the Ministry stopped paying its bills there had been two changes of government. Dr. Sheikholeslamizadeh, who was now in jail, had been replaced by a general; and then, when Bakhtiar became Prime Minister, the general had in turn been replaced by a new Minister of Health. Who, Howell wondered, was the new guy; and what was he like?

'Mr. Young, of the American company EDS, is calling you, Minister,' said the secretary.

Dr. Razmara took a deep breath. 'Tell him that American businessmen may no longer pick up the phone and call ministers of the Iranian government and expect to talk to us as if we were their employees,' he said. He raised his voice. 'Those days are over!'

Then he asked for the EDS file.

Manuchehr Razmara had been in Paris over Christmas. French-educated-he was a cardiologist--and married to a Frenchwoman, he considered France his second home, and spoke fluent French. He was also a member of the Iranian National Medical Council and a friend of Shahpour Bakhtiar, and when Bakhtiar had become Prime Minister he had called his friend Razmara in Paris and asked him to come home to be Minister of Health.

The EDS file was handed to him by Dr. Emrani, the Deputy Minister in charge of Social Security. Emrani had survived the two changes of government: he had been here when the trouble had started.

Razmara read the file with mounting anger. The EDS project was insane. The basic contract price was forty- eight million dollars, with escalators taking it up to a possible ninety million. Razmara recalled that Iran had twelve thousand working doctors to serve a population of thirty-two million, and that there were sixty-four thousand villages without tap water; and he concluded that whoever had signed the deal with EDS were fools or traitors, or both. How could they

Well, they would suffer. Emrani had prepared this dossier for the special court that prosecuted corrupt civil servants. Three people were in jail: former Minister Dr. Sheikholeslamizadeh, and two of his Deputy Ministers, Reza Neghabat and Nili Arame. That was as it should be. The blame for the mess they were in should fall primarily on Iranians. However, the Americans were also culpable. American businessmen and their government had encouraged the Shah in his mad schemes, and had taken their profits: now they must suffer. Furthermore, according to the file, EDS had been spectacularly incompetent: the computers were not yet working, after two and a half years, yet the automation project had so disrupted Emrani's department that the old-fashioned systems were not working either, with the result that Emrani could not monitor his department's expenditure. This was a principal cause of the Ministry's overspending its budget, the file said.

Razmara noted that the U.S. Embassy was protesting about the jailing of the two Americans, Chiapparone and Gaylord, because there was no evidence against them. That was typical of the Americans. Of course there was no proof: bribes were not paid by check. The Embassy was also concerned for the safety of the two prisoners. Razmara found this ironic.

He closed the file. He had no sympathy for EDS or its jailed executives. Even if he had wanted to have them released, he would not have been able to, he reflected. The anti-American mood of the people was rising to fever pitch. The government of which Razmara was a part, the Bakhtiar regime, had been installed by the Shah and was therefore widely suspected of being pro-American. With the country in such turmoil, any Minister who concerned himself with the welfare of a couple of greedy American capitalist lackeys would be sacked if not lynched--and quite rightly. Razmara turned his attention to more important matters.

The next day his secretary said: 'Mr. Young, of the American company EDS, is here asking to see you, Minister.'

The arrogance of the Americans was infuriating. Razmara said: 'Repeat to him the message I gave you yesterday--then give him five minutes to get off the premises.'

4____

For Bill, the big problem was time.

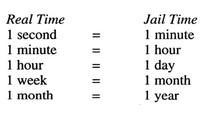

He was different from Paul. For Paul--restless, aggressive, strong-willed, ambitious--the worst of being in jail was the helplessness. Bill was more placid by nature: He accepted that there was nothing to do but pray, so he prayed. (He did not wear his religion on his sleeve: he did his praying late at night, before going to sleep, or early in the morning before the others woke up.) What got to Bill was the excruciating slowness with which time passed. A day in the real world--a day of solving problems, making decisions, taking phone calls, and attending meetings--was no time at all: a day in jail was endless. Bill devised a formula for conversion of real time to jail time.

Time took on this new dimension for Bill after two or three weeks in jail, when he realized there was going to be no quick solution to the problem. Unlike a convicted criminal, he had not been sentenced to ninety days or five years, so he could gain no comfort from scratching a calendar on the wall as a countdown to freedom. It made no difference how many days had passed: his remaining time in jail was indefinite, therefore endless.

His Persian cellmates did not seem to feel this way. It was a revealing cultural contrast: the Americans, trained to get fast results, were tortured by suspense; the Iranians were content to wait for

Nevertheless, as the Shah's grip weakened, Bill thought he saw signs of desperation in some of them, and he came to mistrust them. He was careful not to tell them who was in town from Dallas or what progress was being made in the negotiations for his release: he was afraid that, clutching at straws, they would have tried to trade information to the guards.

He was becoming a well-adjusted jailbird. He learned to ignore dirt and bugs, and he got used to cold, starchy, unappetizing food. He learned to live within a small, clearly defined personal boundary, the prisoner's 'turf.' He stayed active.

He found ways to fill the endless days. He read books, taught Paul chess, exercised in the hall, talked to the Iranians to get every word of the radio and TV news, and prayed. He made a minutely detailed survey of the jail, measuring the cells and the corridors and drawing plans and sketches. He kept a diary, recording every trivial event of jail life, plus everything his visitors told him and all the news. He used initials instead of names and sometimes put in invented incidents or altered versions of real incidents, so that if the diary were confiscated or read by the authorities it would confuse them.

Like prisoners everywhere, he looked forward to visitors as eagerly as a child waiting for Christmas. The EDS people brought decent food, warm clothing, new books, and letters from home. One day Keane Taylor brought a picture of Bill's six-year-old son, Christopher, standing in front of the Christmas tree. Seeing his little boy, even in a photograph, gave Bill strength: a powerful reminder of what he had to hope for, it renewed his resolve to hang on and not despair.

Bill wrote letters to Emily and gave them to Keane, who would read them to her over the phone. Bill had known Keane for ten years, and they were quite close--they had lived together after the evacuation. Bill knew that Keane was not as insensitive as his reputation would indicate--half of that was an act--but still it was embarrassing to write 'I love you' knowing that Keane would be reading it. Bill got over the embarrassment, because he wanted very badly to tell Emily and the children how much he loved them, just in case he never got another chance to say it in person. The letters were like those written by pilots on the eve of a dangerous mission.

The most important gift brought by the visitors was news. The all-too-brief meetings in the low building across the courtyard were spent discussing the various efforts being made to get Paul and Bill out. It seemed to Bill that time was the key factor. Sooner or later, one approach or another had to work. Unfortunately, as time passed, Iran went downhill. The forces of the revolution were gaining momentum. Would EDS get Paul and Bill out before