Mel Starr

A Corpse at St Andrew's Chapel

Chapter 1

I awoke at dawn on the ninth day of April, 1365. Unlike Malmsey, the day did not improve with age.

There have been many days when I have awoken at dawn but have remembered not the circumstances three weeks hence. I remember this day not because of when I awoke, but why, and what I was compelled to do after. Odd, is it not, how one extraordinary event will burn even the mundane surrounding it into a man’s memory.

I have seen other memorable days in my twenty-five years. I recall the day my brother Henry died of plague. I was a child, but I remember well Father Aymer administering extreme unction. Father Aymer wore a spice bag about his neck to protect him from the malady. It did not, and he also succumbed within a fortnight. I can see the pouch yet, in my mind’s eye, swinging from the priest’s neck on a hempen cord as he bent over my stricken brother.

I remember clearly the day in 1361 when William of Garstang died. William and I and two others shared a room on St Michael’s Street, Oxford, while we studied at Baliol College. I comforted William as the returning plague covered his body with erupting buboes. For my small service he gave me, with his last breaths, his three books. One of these volumes was

Was it then God’s will that William die a miserable death so that I might find God’s vision for my life? This I cannot accept, for I saw William’s body covered with oozing pustules. I will not believe such a death is God’s choice for any man. Here I must admit a disagreement with Master Wyclif, who believes that all is foreordained. But out of evil God may draw good, as I believe He did when he introduced me to the practice of surgery. Perhaps the good I have done with my skills balances the torment William suffered in his death. But not for William.

I remember well the day I met Lord Gilbert Talbot. I stitched him up after his leg was opened by a kick from a groom’s horse on Oxford High Street. This needlework opened my life to service to Lord Gilbert and the townsmen of Bampton, and brought me also the post of bailiff on Lord Gilbert’s manor at Bampton.

Other days return to my mind with less pleasure. I will not soon forget Christmas Day 1363, and the feast that day at Lord Gilbert’s Goodrich Castle hall. I had traveled there from Bampton to attend Lord Gilbert’s sister, the Lady Joan. The fair Joan had broken a wrist in a fall from a horse. I was summoned to set the break. It was foolish of me to think I might win this lady, but love has hoped more foolishness than that. A few days before Christmas a guest, Sir Charles de Burgh, arrived at Goodrich. Lord Gilbert invited him knowing well he might be a thief. Indeed, he stole Lady Joan’s heart. Between the second and third removes of the Christmas feast he stood and, for all in the hall to see, offered Lady Joan a clove-studded pear. She took the fruit and with a smile delicately drew a clove from the pear with her teeth. They married in September, a few days before Michaelmas, last year.

I digress. I awoke at dawn to thumping on my chamber door. I blinked sleep from my eyes, crawled from my bed, and stumbled to the door. I opened it as Wilfred the porter was about to rap on it again.

“It’s Alan…the beadle. He’s found.”

Alan had left his home to seek those who would violate curfew two days earlier. He never returned. His young wife came to me in alarm the morning of the next day. I sent John Holcutt, the reeve, to gather a party of searchers, but they found no trace of the man. John was not pleased to lose a day of work from six men. Plowing of fallow fields was not yet finished. Before I retired on Wednesday evening, John sought me out and begged not to resume the search the next day. I agreed. If Alan could not be found with the entire town aware of his absence, another day of poking into haymows and barns seemed likely also to be fruitless. It was not necessary.

“Has he come home?” I asked.

“Nay. An’ not likely to, but on a hurdle.”

“He’s dead?”

“Aye.”

“Where was he found?”

“Aside the way near to St Andrew’s Chapel.”

It was no wonder the searchers had not found him. St Andrew’s Chapel was near half a mile to the east. What, I wondered, drew him away from the town on his duties?

“Hubert Shillside has been told. He would have you accompany him to the place.”

“Send word I will see him straight away.”

I suppose I was suspicious already that this death was not natural. I believe it to be a character flaw if a man be too mistrustful. But there are occasions in my professions — surgery and bailiff — when it is good to doubt a first impression. Alan was not yet thirty years old. He had a half-yardland of Lord Gilbert Talbot and was so well thought of that despite his youth, Lord Gilbert’s tenants had at hallmote chosen him beadle these three years. He worked diligently, and bragged all winter that his four acres of oats had brought him nearly five bushels for every bushel of seed. A remarkable accomplishment, for his land was no better than any other surrounding Bampton. This success brought also some envy, I think, and perhaps there were wives who contrasted his achievement to the work of their husbands. But this, I thought, was no reason to kill a man.

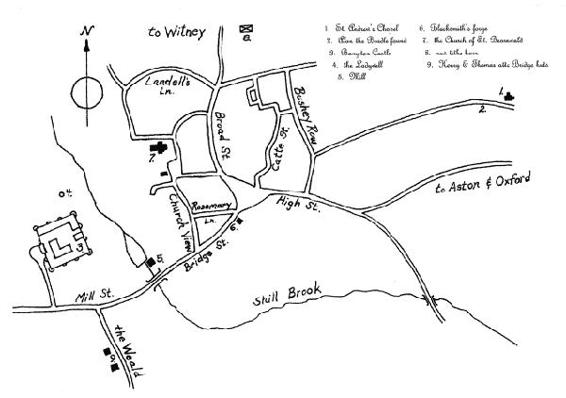

I suppose a man may have enemies which even his friends know not of. I did consider Alan a friend, as did most others of the town. On my walk from Bampton Castle to Hubert Shillside’s shop and house on Church View Street, I persuaded myself that this must be a natural death. Of course, when a corpse is found in open country, the hue and cry must be raised even if the body be stiff and cold. So Hubert, the town coroner, and I, bailiff and surgeon, must do our work.

Alan was found but a few minutes from the town. Down Rosemary Lane to the High Street, then left on Bushey Row to the path to St Andrew’s Chapel. We saw — Hubert and I, and John Holcutt, who came also — where the body lay while we were yet far off. As we passed the last house on the lane east from Bampton to the chapel, we saw a group of men standing in the track at a place where last year’s fallow was being plowed for spring planting. They saw us approach, and stepped back respectfully as we reached them.

A hedgerow had grown up among rocks between the lane and the field. New leaves of pale green decorated stalks of nettles, thistles and wild roses. Had the foliage matured for another fortnight Alan might have gone undiscovered. But two plowmen, getting an early start on their day’s labor, found the corpse as they turned the oxen at the end of their first furrow. It had been barely light enough to see the white foot protruding from the hedgerow. The plowman who goaded the team saw it as he prodded the lead beasts to turn.

Alan’s body was invisible from the road, but by pushing back nettles and thorns — carefully — we could see him curled as if asleep amongst the brambles. I directed two onlookers to retrieve the body. Rank has its privileges. Better they be nettle-stung than we. A few minutes later Alan the beadle lay stretched out on the path.

Lying in the open, on the road, the beadle did not seem so at peace as in the hedgerow. Deep scratches lacerated his face, hands and forearms. His clothes were torn, his feet bare, and a great wound bloodied his neck where flesh had been torn away. The coroner bent to examine this injury more closely.

“Some beast has done this, I think,” he muttered as he stood. “See how his surcoat is torn at the arms, as if he tried to defend himself from fangs.”

I knelt on the opposite side of the corpse to view in my turn the wound which took the life of Alan the beadle. It seemed as Hubert Shillside said. Puncture wounds spread across neck and arms, and rips on surcoat and flesh indicated where claws and fangs had made their mark. I sent the reeve back to Bampton Castle for a horse on which to transport Alan back to the town and to his wife. The others who stood in the path began to drift away. The plowmen who found him returned to their team. Soon only the coroner and I remained to guard the corpse. It needed guarding. Already a flock of carrion crows flapped high above the path.