Dudley Pope

Ramage's Signal

For Ian Spencer

CHAPTER ONE

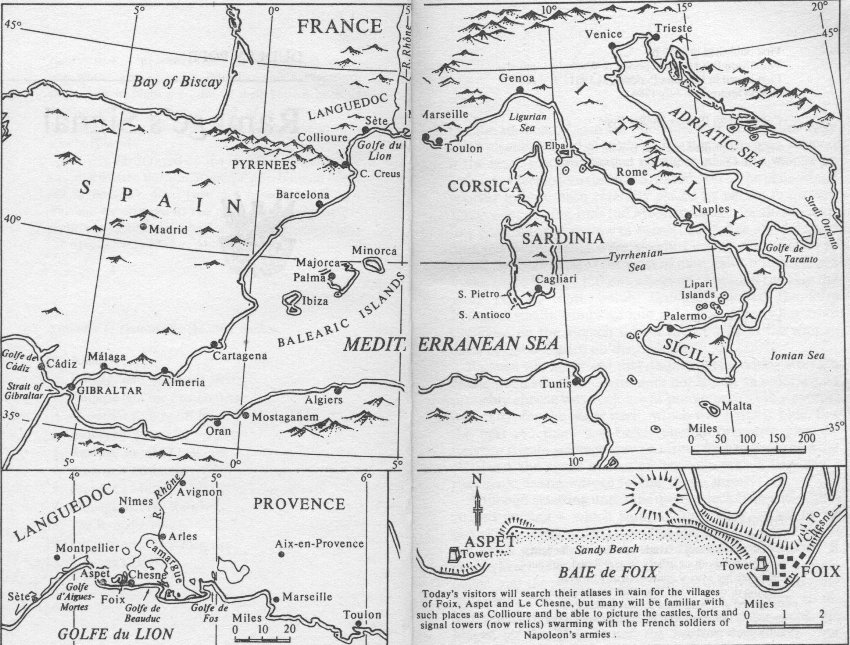

On the starboard beam the shoreline just three miles away was a gleaming band of sand shimmering in the heat. Beyond it the land, scorched brown by the summer sun, sloped up only a few feet to join the broad, flat ribbon of the plain which seemed to have been carefully placed by nature to prevent Languedoc sliding into the Mediterranean. Farther inland, like haze in the afterglow of sunset, a low line of ridged and dimpled purple hills were slowly turning deep mauve to reveal the beginning of the mass of mountains running north to the Loire Valley, 150 miles beyond. Ahead of the ship the same purple, more boldly brushed, showed the lofty Pyrenees finally tumbling into the sea, a jagged line from Collioure on the French side of the frontier to the whitish cliffs of Cabo Lladró on the Spanish.

Ramage was surprised that despite the scorching strength of the noon sun the colours were not harsh; an artist would probably choose watercolours in preference to oils - except, ironically, for the water itself, which was a strong blue. But the heat ... there was barely enough breeze to give the Calypso frigate steerage way and from time to time the wind collapsed the slight curves of her sails with a flap like a rheumatic washerwoman folding damp sheets.

Although standing under the quarterdeck blue-and-white-striped awning - which stopped him being cooled by an occasional downdraught from the mainsail - Ramage found the sun's glare dazzling because the wavelets reflected it everywhere, like the diamond-shaped pendants of a chandelier, and the muscles controlling his eyebrows ached from squinting. The planking of the deck was scorching, so his feet were swollen from the heat and tight in his shoes. He longed for the West Indies: the Tropics were hotter - but they had the regular cooling Trade winds.

He realized he was dozing although standing up, a trick learned by most midshipmen, when he heard Southwick, the master, bellowing aloft in reply to a lookout's hail, and roused himself sufficiently to listen to the report - not that it would be anything interesting: this part of the French coast was typically 'in between', one of those tedious stretches of uninteresting land on the way to somewhere else.

'The village on the beam, sir: there's a sort of tall framework tower at the western end, an' begging yer pardon, sir, it's movin'.'

'The tower or the village?' demanded the practical master, who was already looking round for his telescope.

'The tower, sir. There! It's - well, it looks as though it's winking!'

The disbelief in the seaman's voice, as though he was reporting a ghost, made Ramage snatch up his own telescope, pull out the two brass tubes until the eyepiece end lined up with a mark filed on the second, and steady the glass by leaning his elbows on the quarterdeck rail. With so little wind and sea the ship was not rolling and using a glass needed no feat of balancing.

There, encircled by the lens, was the tower. And close to it four or five new wooden buildings which seemed to be more than huts but less than regular barracks. This was what the lookout meant by 'the village', and the tower did appear to be winking. He gripped the telescope firmly and stared harder. Or blinking.

He heard Southwick's puzzled grunts and a moment later an exclamation from the Scots first lieutenant, Aitken. 'If there were hills and trees I'd say it was an enormous, great hide for shooting deer', Aitken murmured as though talking to himself, 'but here, where it's more like a desert...'

As the Calypso moved slowly along the coast the tower's angle changed, and Ramage suddenly realized that what at first seemed to be a square, wooden tower was simply a large rectangle of wood perhaps forty feet high, like a door without a frame or wall, its edge at right angles to the sea. As you approached you saw one side as a rectangle and assumed it was a cube. As you came abreast of it, all you saw was something that looked like a pine tree stripped of its branches, and as you passed and looked back you saw the other side of the rectangle.

It was a rectangle which looked like a section of a chess board and in which, even as he watched, one or two squares winked or blinked - or just moved.

Then he realized that it must be one of the new French semaphore towers, and at this very moment it was passing a message along the coast. But which way? The nearest village to this tower was Foix. But where were the other towers? The Calypso must have passed several, but unless the angle was right the lookouts would have seen them end-on - and this coast was littered with the bare trunks of pine trees which had died among the sand dunes, killed by harsh winds or goats or rats gnawing the bark.

Southwick and Aitken had both given up looking at the tower and were watching him, puzzled.

'It's one of the new semaphore towers', Ramage explained. 'The winking is the shutters opening and closing as they pass a message.'

'What are they signalling, I wonder', Aitken mused.

'It shows either that they must have a powerful glass and can see our colours, or they recognize a French ship', Southwick commented.

'More important, no general warning has been passed to them - or any French forces - to watch for a French frigate captured by the British', Ramage said.

'They might be passing the warning now', Southwick said with a chuckle that set his bulging stomach trembling and was a sign that he hoped action was on its way. 'Telling someone else along the coast that they've sighted us.'

'How far could you distinguish the pattern of those squares if you had a powerful glass on a tripod and good light?' Ramage asked Aitken, who put his telescope back to his eye.

'I reckon it's two miles away now, sir. I can just see the wavelets on the beach. Ah - there's a man walking, so the shutters are about six feet square. Say a dozen miles, sir.'

'Well, I doubt if they're warning anyone about us', Ramage said briskly, 'because we must have passed several of these towers already without recognizing them, and each would have seen us and could have reported it.'

'Perhaps this one is just reporting that we're passing now?' Aitken ventured.

Ramage shook his head. 'What are we making? Perhaps two knots. We've been in sight - close enough for them to identify us as a frigate - for more than an hour. They'd have passed such a message a long time ago.'

'They've stopped signalling now', Aitken said. 'Two men are walking away from the base of the tower, making for a hut. Ah, now there's a third who seems to have come down a ladder from the top of the tower.'

'Where are they going?' Ramage asked sharply. 'Note which hut.'

'The third man is carrying something rather carefully . . .'

'A telescope?'

'Yes, sir, it could be.'

'He was probably watching the next tower acknowledging each word of the signal.'

'Ah, I can see a little platform on top', Aitken said. 'The ladder goes up to it. Even has an awning. Trust the French. A shelf for a flask of wine, too, I'll be bound.'

From the tone of Aitken's voice, with its soft Perthshire accent, it was hard to know whether the sin was in the luxury of the awning, the drinking of wine, or being French. Ramage finally decided it was probably all three.

'Two are going to the first hut on the west side of the headland and which has a flagpole outside; one - the man with the telescope - is going to the next farther inland, probably reporting to the garrison commander. Now another man has just walked round the base of the tower and gone to the third on the east side. The fourth and fifth huts are the same size. There's a sixth, much smaller and with a chimney. Probably the kitchen.'

Ramage looked through his telescope. Each hut could accommodate at least a dozen men. What size would the garrison be? Three men were needed to pass a signal, so a signal watch would comprise three men. They would be on duty only during daylight, which in summer lasted about sixteen hours. Four hours on and four off meant two watches a day for six men. Plus a cook. Plus sentries - two on duty at any one time throughout the twenty-four hours. Two hours on and six off. Eight men.

The province's Army commander would hardly have welcomed the setting up of the semaphore stations if each one needed six signalmen, eight infantrymen and a cook. And knowing how expert were soldiers (and sailors, too!) in getting authorization to have the largest complement to do the least work, there'd be a lieutenant as the commanding officer, a quartermaster and probably even a carpenter and his mate to do repairs when an extra strong gust from a mistral or Levanter blew out some panels of the semaphore shutters. At least nineteen or twenty men; more counting sergeants and corporals. It seemed absurd but, to be fair, a soldier would never understand why the official complement of the Calypso, a 32-gun frigate, was 230 men - not that she was ever lucky enough to have that many, in the same way that any battalion was usually short of men.

Ramage looked up to find Southwick watching him, his chubby, suntanned face wrinkled in an unspoken question. The old man had taken off his hat, and his white hair, in need of a trim and soaked with perspiration, looked like a new mop just dipped in a bucket of water and shaken. Aitken had closed his telescope and was waiting too. Rennick, the Marine lieutenant, had joined them, anxious not to miss anything.

In the meantime the Calypso was stretching along to the westward, a few miles short of the little town of Foix, flying French colours as a legitimate ruse de