frankness in twenty years.

I told her I had to go because my son and two other students were waiting for me, but that I wanted to bring PanPan to see her after lunch. She clearly didn't believe she'd see me again. 'Come back if you've time,' she shrugged. 'You look like a busy person.'

A little while after noon, PanPan, a couple of female students and I reappeared in front of her shop. 'So you really did come back,' she beamed at us. 'And with these fine young people! Sit down, I've stools for all of you.'

She seemed to have just finished her lunch: an empty bowl and pair of chopsticks were lying in the bamboo basket next to her, along with a handful of spring onions and some wild mountain peppers. The Hunanese can eat furiously spicy food. Perhaps she was taking advantage of a lull in business to prepare dinner. An ancient Thermos flask stood next to the basket, alongside a rubbish-filled shopping bag.

I told her that PanPan wanted to give her a poster of London. Also, one of the students, Y, wanted something for her skin allergy, while the other student, K, wanted to take some professional-quality photos of her. Though I'd expected her to refuse to be photographed, she seemed delighted and immediately agreed, even thanking us for our time.

She was very taken with the poster of Tower Bridge. 'What a beautiful building!' she exclaimed to herself. 'The bridge opens, you say? I've never seen anything like it! What country is London in? Why's it called London? What does it mean?' As I had no answers to her questions, I pushed Y forward. 'Could you take a look at her?'

Y pulled up her shirt. Her skin looked terrible, covered in great patches of suppurating lumps and bumps. Without blinking an eye, Yao Popo beckoned her inside. 'Three doses of my medicine and it'll be better.'

Y and I followed her doubtfully into the shop, where she got down from a shelf a wooden box filled with ground walnuts, peanuts and red dates, on which a number of small brown-winged insects were feeding. Yao Popo then got Y to pick out twenty-one of the fattest, liveliest insects, which she deftly caught and divided between three blue- and-white medicine capsules. She instructed the student to take the three capsules over the course of a single day – checking that the insects were still alive before swallowing them – and to take the first now. 'Don't be afraid,' she told Y as she passed her the first capsule, 'I've fed them only on nuts and fruit. They're much cleaner inside than us.'

Y looked first at the insects wriggling inside the capsule, and then questioningly at me. I didn't know what to say to her. After a brief hesitation, she asked me to pour her a large cup of water. She took a deep breath then, still rather nervously, swallowed the capsule down. I was impressed by her intrepidity – a rare quality among her generation of cosseted only children.

She obeyed the Medicine Woman's instructions to the letter, swallowing the remaining two doses over the next twelve hours, checking both times that the insects were still alive. Very soon, her itching stopped; a couple of days later, her scabbed skin miraculously healed over.

Just before we said goodbye, Yao Popo told us about the unhappiest and the happiest times in her life. Her first great source of unhappiness had been growing up without parents, without a home of her own, and with only a damp mud floor to sleep on. The second hardest thing had been bringing up seven children in a tiny room of only twelve metres square. While they were small, she'd not had a moment's peace, day or night. The third had been breaking the bridge of her beautiful nose. A good nose, she said, was a woman's most important feature. The single thing that brought her greatest happiness was that all her children had survived the famine of the 1950s and '60s in which so many millions had died, and that her grandchildren had gone to school and had children of their own. The second great blessing for which she was thankful was that her husband had never hit her. Her third source of pleasure over the years had been sitting in front of the shop, day in, day out, watching the world changing around her.

'In the thirty or forty years I've been sitting here, the city centre's changed every time someone has taken over the local government,' she said, pointing to the buildings towering over her poky lane. 'Those houses to your left date from the 1950s. Hardly anything was built during the Cultural Revolution, but the ones opposite are from the 1980s, while the buildings to the right went up within the last two years. Now I hear the new mayor wants to rip them down and start again! As soon as they have a bit of cash in their pockets, officials always want to show off, changing everything too quickly for anyone to catch up. But no one's ever thought of fixing this crumbling old lane of ours, even though hundreds of people live here. I'll retire when they finally do something about that,' she laughed.

We waved goodbye to Yao Popo, but every straight nose I have since seen has made me think of her – an old woman whose yearning for beauty had not been ground out of her by poverty.

2 Two Generations of the Lin Family: the Curse of a Legend

From left , the 'Double-Gun Woman', Lin Zhuxi (Mr Lin's father), her son-in-law Lin Xiangbei, and his wife.

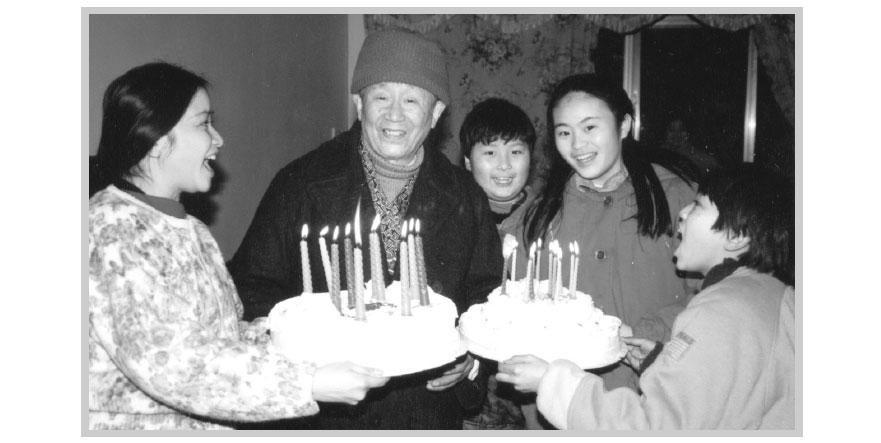

Mr Lin with his daughter and grandchildren.

LIN XIANGBEI, aged eighty-nine, son and son-in-law of revolutionary martyrs,

In China, the 'Double-Gun Woman' is a national heroine: a legendary female revolutionary, ruthlessly dispatching enemies and traitors with a gun in each hand, dry-eyed even at the deaths of her husband and children – as fast as a bandit, as tough as a peasant.

In the Archives of the Imperial Academy stored in Beijing Library (which, by some miracle, survived the Cultural Revolution), we can trace the family history of the Double-Gun Woman, Chen Lianshi, back through several generations. Her earliest traceable ancestor on her mother's side is an imperial academician from Sichuan called Kang Yiming, who served during the reign of the Qing emperor Jiaqing (1796-1820). Her father's forebears were equally illustrious, many of them scholar-officials or high-ranking military men.

After the foundation of the Republic in 1912, several members of the family left Sichuan to study elsewhere, some heading to Japan, some joining Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary Tongmeng Society. Having been, in the last years of the Qing, a high-ranking official renowned for his justness and benevolence, and for his work in helping the poor and needy, her father was selected as member of parliament for the area.

Sources that emerged during the 1980s state that, as a girl, 'the Double-Gun Woman demonstrated exceptional intelligence, covering in two and a half years the curriculum that took most students seven. After enrolling at the local women's Normal College, she then passed the entrance examination to one of the country's top universities in Nanjing, where she hoped to help her country by studying to become a teacher. She excelled also at painting.' The Double-Gun Woman was clearly neither a poor peasant, nor an illiterate bandit.

In Communist China, the designation of national heroes has been a fiercely controlled business. Under Mao, in particular, only members of the proletariat – workers or peasants – were officially permitted to be heroic. More or less since Chinese history began, the country's great patriotic heroes have been mostly male: unflinching individuals permitted to shed tears in only two cataclysmic sets of circumstances: at the death of their mother, or the loss of the motherland. With the rise to power of the Communists – and of the idea that 'women hold up half the sky' – women, too, were allowed to become national heroes, but only in the superhuman, patriotic male mould. When I was very small, I saw