Jingguan.

On 30 December 2006, I had just edited the second draft of

On 1 January 2007, the Supreme People's Court is to implement a policy requiring ratification by the Supreme People's Court of all death sentences handed down by lower courts. This is a historically significant step in the development of Chinese criminal law, not only for China's criminal justice work, but also for the progress and development of the Chinese legal system.

With regard to criminal cases, China operates a system of the Court of Second Instance being the Court of Last Instance. Judicial review of death sentences falls outside the First and Second Instance system, and there are special procedures set up which are targeted at death penalty cases. After New China was established, the policy of retaining and strictly controlling the death sentence was implemented and the ratification system for death sentences was set up. In 1954, regulations on the organisation of the People's Courts were issued and these decreed that death penalty cases must be ratified by the Supreme People's Court and the Higher People's Courts. In a decision made at the fourth session of the First People's Congress in 1957, all death-penalty cases were thenceforth to be decided or ratified by the Supreme People's Court. Between 1957 and 1966, all death penalties were ratified by the Supreme People's Court.

During the Cultural Revolution, the People's Courts came under heavy attack, and the system of ratifying death sentences ceased to operate except in name. In July 1979, the second session of the Fifth National People's Congress passed the Chinese Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Law, revising the organisation of the People's Courts. It was decreed that all death sentences other than those passed by the Supreme People's Court, must be approved by the latter. However, in February 1980, not long after the Chinese Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Law had been passed, another decision was passed by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, with the aim of meting out swift and severe punishment to criminal elements who had seriously jeopardised the social order: the Supreme People's Court thereby authorised Higher People's Courts to handle some death-sentence cases for a limited period. Following further reforms of the organisation of the People's Courts, and repeated delegation of authority, this system has persisted up to the present day.

My first reaction was to telephone Mr Jingguan. I hoped I would hear him say: Finally the Supreme Court has reclaimed the right to confirm the death sentence, and removed it from the hands of muddled and incompetent judges who indiscriminately execute the innocent! But when I called him, just before the Spring Festival in 2007, to send him and his family season's greetings, and we talked about the new legislation, the old policeman said: 'These are just words on paper, miles away from the heads of the people who deal with the cases. It's only when everyone is capable of understanding the significance of those words that people will understand the law, and the law enforcers will no longer dare persist in their reckless ignorance. How many people has China tortured? How many 'Clear Sky Baos' are there?'

From the first Qin emperor of China, and the first law to operate on the principle that 'the nine clans bore responsibility for the misdemeanours of their members', to a China, two thousand years later, which has just emerged from political adversity, the ghostly wails of the countless wrongly accused, victims of corrupt local officials who use their power to trifle with human lives, echo down the centuries. In two thousand years of Chinese history, for all our boasting about our ancient political and judicial system, there has only been one great judge, the Song dynasty's Justice 'Clear Sky Bao', known to every Chinese for his uncompromising honesty. Just one.

11 The Shoe-Mender Mother: 28 Years Spent out in All Weathers

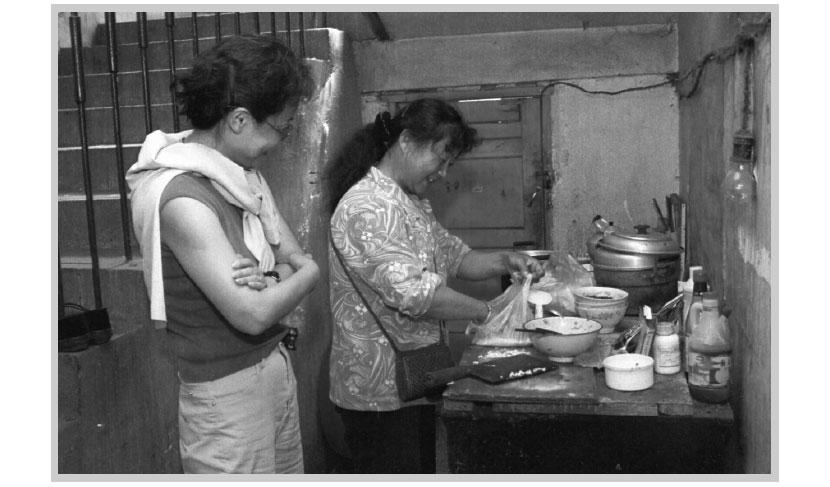

The shoe-mender woman, Zhengzhou, was at first shy of our camera…

… but later invited us home for lunch.

MRS Xie, a shoe-mender,

The way I saw it in 2006, there are five kinds of roads in China.

The first kind is what are called the national roads – fast highways planned and built at the national level and maintained by local government. I could clearly 'feel' the difference between those built after 2000 and those built before; on the newer ones, you didn't get the stomach-churning effects of their appallingly fissured and bumpy surfaces. Nor did you need to hire a local guide to alert you to traffic hazards along the road, although not even the newest map could steer you accurately through the ever-changing road system. The toilets on the national highways are 'national-grade toilets' and are, most of them, much better than the houses the local peasants live in. No wonder a lot of drivers say that these highways are not only good for driving on – you get 'national-grade' treatment while you're at it.

The second kind are city trunk roads built by the municipal government and generally very wide: six to ten lanes in big cities, two to four in smaller ones. The roadsides reflect a government image and vary little in their 'local touches'. They are uniformly lined with tower blocks and smaller buildings, flowers or sculptures. The wealthier municipalities have real flowers, the ones that have no money use plastic ones. In most cases, there are pavement studs for blind pedestrians. The traffic lights show a standing person on red, and a scuttling one on green. The most enjoyable thing about them for ordinary Chinese who can't afford cars is the wide green verges, squares and benches on which you can sit and chat and get a breath of fresh air. They are unlike the city roads of ten years ago. Then, scooters, mopeds, bicycles and pedestrians were all jumbled together. The narrow pavements were too packed to move during peak times, and all you could hear were car horns tooting in competition with each other, the endless cursing of drivers as they jockeyed for position, and the shouted admonishments of the traffic cops.

The third kind are streets in working-class districts. There are more bicycles than people and cars, the streets are narrow, and there is only a single lane for scooters, into which vehicles going in both directions are squeezed by traffic jams on the main carriageway. The sides of the roads are crammed with daily necessities and everyday life, businesses and things. There you can see people who yesterday ran stalls, and today have opened shops. The space where goods are piled high during the day is converted at night into the place where the family eats and sleeps. These city streets are more or less equivalent to the high streets of a small country town, although with fewer agricultural items and cheap plastic goods.

The fourth kind are the back streets and alleys which link the homes of the teeming populace. These are chiefly inhabited by small traders and craftspeople who have come in from the villages to 'make their fortune' in the big city, and make a start by setting up stalls and kiosks. There are a few cars who don't believe that the streets are impassable to traffic until, half an hour later, they have proudly made it fifty metres through the people and goods only to discover that their triumphant vehicles are a mass of scrapes and scratches and bespattered in grime. These back streets are one big 'breakfast bar' in the morning, a street market by day and a kind of leisure market in the evening, providing profits all day. The beneficiaries of all this activity are the residents' committees. In order to ensure that 'no manure should escape onto someone else's land', the levels of administration are the most regulated in China; there are toilet attendants, security guards, overseers of regulations, administrators of local