as its enemy even before China itself had decided to be America’s enemy.

Moreover, a US-India alliance would be a gratis favor to Russia without any Russian favor in return. In fact, such an alliance would be inimical in two significant ways to long-term American interests in Eurasia: it would reduce Russian fears of China and thus diminish Russian self-interest in becoming more closely tied to the West, and it would increase Moscow’s temptations to take advantage of a distracted America drawn into wider Asian conflicts to assert Russian imperial interests more firmly in Central Asia and in Central Europe. Prospects for a more vital and larger West would thereby become more remote.

Finally, an America-India alliance would also be likely to intensify the appeal of anti-American terrorism among Muslims, who would infer that this partnership was implicitly directed against Pakistan. That would be even more likely if in the meantime religious violence between Hindus and Muslims erupted in parts of India. Much of the rest of the Islamic world, be it in nearby southwest Asia or in Central Asia or in the Middle East, would be roused into mounting sympathy and then support for terrorist acts directed at America. In brief, insofar as the first Asian triangle is concerned, the better part of wisdom is abstention from any alliance that could obligate the United States to military involvement in that part of Asia.

The issue is not so clear-cut with regard to the second regional triangle involving China, Japan, South Korea, and to a lesser degree Southeast Asia. More generally, this issue pertains to China’s role as the dominant power on the Asian mainland and to the nature of America’s position in the Pacific. Japan is America’s key political-military ally in the Far East even though its military capabilities are currently self-restrained, a condition that may be fading because of growing concerns over China’s rising power. It is also the world’s number three economic power, having only recently been surpassed by China. South Korea is a burgeoning economic power and longtime American ally that relies on the United States to deter any possible conflict with its estranged northern relative. Southeast Asia has less formal ties to the United States and has a strong regional partnership (ASEAN), but it fears the growth of Chinese power. Most importantly, America and China already have an economic relationship that makes both vulnerable to any reciprocal hostility, while the growth of China’s economic and political power poses a potential future challenge to America’s current global preeminence.

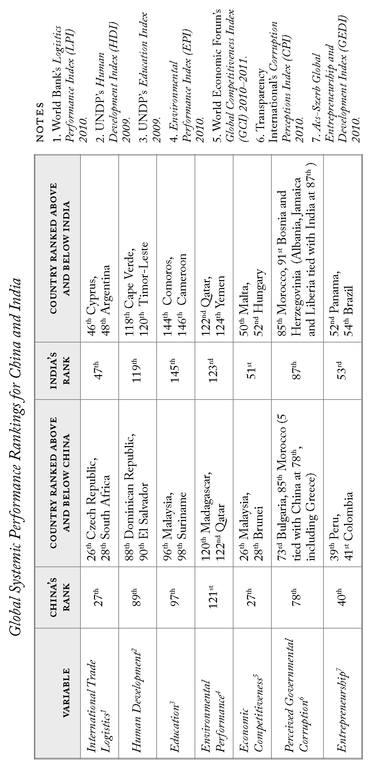

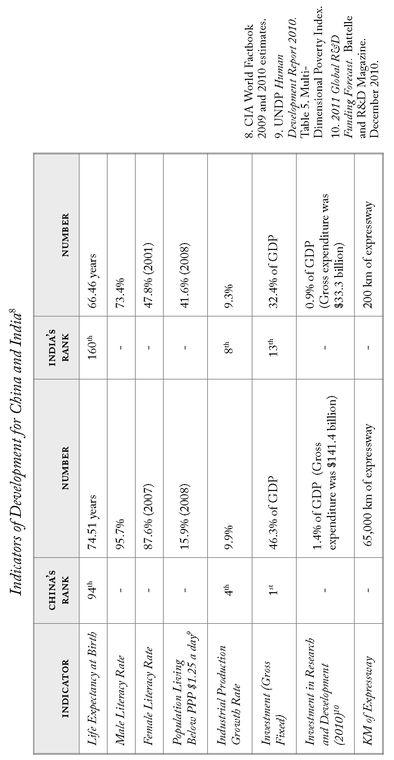

FIGURE 4.3 GLOBAL SYSTEMIC PERFORMANCE RANKINGS FOR CHINA AND INDIA, AND INDICATORS OF DEVELOPMENT FOR CHINA AND INDIA

Given China’s recent performance, as well as its historical accomplishments, it would be rash to assume that the Chinese economy might suddenly grind to a halt. Back in 1995 (in effect, then at the midpoint of China’s now thirty-year-long economic takeoff ), some prominent American economists even suggested that by 2010 China might find itself in the same dire straits as the Soviet Union did some thirty years ago after the phantasmagoric official Soviet claims of the 1960s that by 1980 the Soviet Union would surpass America in economic power. By now, it is evident even to the most skeptical that China’s economic ascent has been real and that it has a good chance of continuing for a while, though probably at declining annual rates.

That is not to deny that China could be adversely affected by an international decline in demand for Chinese manufactured goods or by a worldwide financial crisis. Also, social tensions in China could rise because of widening social disparities. They could generate political restlessness, of which the historic Tiananmen Square events of 1989 could in some respects be a preview. The new Chinese middle class, now amounting by some counts to about 300 million people, may demand more political rights. But none of that would be reminiscent of the Soviet Union’s systemic disaster. China’s influential and rising role in world affairs is a reality to which Americans will have to adjust—instead of either demonizing it or engaging in thinly concealed wishful thinking about its failure.

The more serious danger could come from an altogether different source, less economic and more social- political in character. It could surface as the result of a gradual and initially imperceptible decline in the quality of Chinese leadership or of a more perceptible rise in the intensity of Chinese nationalism. Either of the two, or both combined, could produce policies harmful to China’s international aspirations and/or could prove disruptive to China’s tranquil domestic transformation.

Till now, the performance of the Chinese leadership since the Cultural Revolution has generally been prudent. Deng Xiaoping had vision and determination guided by pragmatic realism. Since Deng, China has gone through three stable leadership renewals thanks, in part, to standardized procedures for firmly scheduled leadership succession. His successors have occasionally differed among themselves (for example, Hu Yaobang, briefly Deng’s heir apparent, advocated more political pluralism than was digestible by his comrades). The Chinese leaders have made efforts to anticipate problems, and even to study jointly pertinent foreign experience in tackling the unavoidable complications of domestic policy successes. (In quite a remarkable exercise, the Chinese politburo periodically convenes to study for a whole day some major external or internal issue in order to draw relevant foreign and historical parallels. The very first session dealt, rather revealingly, with the lessons to be learned from the rise and fall of foreign empires, with the most recent identified as being the American.)

The current generation of leaders, no longer revolutionaries or innovators themselves, have thus matured in an established political setting in which the major issues of national policy have been set on a long-term course. Bureaucratic stability—indeed, centralized control—must seem to them to be the only solid foundation for effective government. But in a highly bureaucratized political setting, conformity, caution, and currying favor with superiors often count for more in advancing a political career than personal courage and individual initiative. Over the longer run, it is questionable whether any political leadership can long remain vital if it is so structured in its personnel policy that it becomes, almost unknowingly, inimical to talent and hostile to innovation. Decay can set in, while the stability of the political system can be endangered if a gap develops between its officially proclaimed orthodoxies and the disparate aspirations of an increasingly politically awakened population.

In the case of China, however, public disaffection is not likely to express itself through a massive quest for democracy but more likely either through social grievances or nationalistic passions. The government is more aware of the former and has been preparing for it. Official planners have even identified publicly and quite frankly the five major threats that in their view could produce mass incidents threatening social stability: (1) disparity between rich and poor, (2) urban unrest and discontent, (3) a culture of corruption, (4) unemployment, and (5) loss of social trust.[20]

The rise of nationalistic passions could prove more difficult to handle. It is already evident, even from officially controlled publications, that intense Chinese nationalism is on the rise. Though the regime in power still advocates caution in the definition of China’s standing and historical goals, by 2009 the more serious Chinese media became permeated by triumphalist assertions of China’s growing eminence, economic might, and its continued ascent to global preeminence. The potential for a sudden rise in populist passions also became evident in outbursts of demonstrative public anger over some relatively minor naval incidents with Japan near disputed islands. The issue of Taiwan could likewise at some point ignite belligerent public passions against America.

Indeed, the paradox of China’s future is that an eventual evolution toward some aspects of democracy may be more feasible under an intelligent but assertive leadership that cautiously channels social pressures for more participation than under an enfeebled leadership that overindulges them. A weakened and gradually more mediocre regime could become tempted by the notion that political unity, as well as its own power, can best be preserved by a policy that embraces the more impatient and more extreme nationalistic definition of China’s future. If a leadership fearful of losing its grip on power and declining in vision were to support the nationalist surge, the result could be a disruption of the so far carefully calculated balance between the promotion of China’s domestic aspirations and prudent pursuit of China’s foreign policy interests.

The foregoing could also precipitate a fundamental change in China’s structure of political power. The Chinese army (the People’s Liberation Army) is the only nationwide organization capable of asserting national control. It is also heavily involved in the direct management of major economic assets. In the event of a serious decline in the vitality of the existing political leadership and of a rise in populist emotions, the military would most likely assume effective control. Paradoxically, the likelihood of such an eventuality is enhanced by the deliberate politicization of the Chinese officer corps. In the top ranks party membership is 100%. And like the CCP itself, party members in the PLA see themselves as being above the state. In the event of a systemic crisis, for the Communist Party members in uniform the assumption of power would thus be the normal thing to do. And political leadership would thus pass into the hands of a highly motivated, very nationalistic, well-organized, but internationally