and urge the agreement’s quick passage.

Back in the Oval Office, I started calling Republican House members to lock in votes.

“We really need this package,” I told one congressman after the next. They all had reasons why they couldn’t vote for it. The price tag was too high. Their constituents opposed it.

“I just can’t bail out Wall Street,” one told me. “I’m not going to be part of the destruction of the free market.”

“Do you think I like the idea of doing this?” I shot back. “Believe me, I’d be fine if these companies fail. But the whole economy is on the line. The son of a bitch is going to go down if we don’t step in.”

At 2:07 p.m., the final vote on the bill was cast. It failed, 228 to 205. Democrats had voted in favor of the legislation, 140 to 95. Republicans had rejected it, with 65 votes in favor and 133 opposed

I knew the vote would be a disaster. My party had played the leading role in killing TARP. Now Republicans would be blamed for the consequences.

Within minutes, the stock market went into free fall. The Dow dropped 777 points, the largest single-day point loss in its 112-year history. The S&P 500 dropped 8.8 percent, its biggest percentage loss since the Black Monday crash of 1987. “This is panic … and fear run amok,” one analyst told CNBC. “Right now we are in a classic moment of financial meltdown.”

Shortly after the vote, I met with Hank, Ben, and the rest of the economic team in the Roosevelt Room to figure out our next move. We really had only one option. We had to make another run at the legislation.

My hope was that the market’s severe reaction would provide a wakeup call to Congress. Many of those who voted against the bill had based their opposition on the $700 billion price tag. Then they had watched the markets hemorrhage $1.2 trillion in less than three hours. Every constituent with an IRA, a pension, or an E*Trade account would be furious.

We devised a strategy, lead by Josh Bolten, to bring the bill up in the Senate first and then make another run in the House. Harry Reid and Mitch McConnell quickly moved a bill with several new provisions intended to attract greater support, including a temporary increase in FDIC insurance for depositors and protections for middle-class families against the Alternative Minimum Tax. The core of the legislation—the $700 billion to strengthen the banks and unfreeze the credit markets—was unchanged.

The Senate held a vote Wednesday night, and the bill passed 74 to 25. The House voted two days later, on Friday, October 3. I made another round of calls to wavering members. My warnings about the system going down had a lot more credibility this time. Thanks to strong leadership from Republican Whip Roy Blunt and Democratic Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, the bill passed 263 to 171. “Monday I cast a blue collar vote,” said one member who changed his position. “Today I’m going to cast a red, white, and blue collar vote.”

Days after I signed TARP, Hank recommended a change in the way we deployed the $700 billion. Instead of buying toxic assets, he proposed that Treasury inject capital directly into struggling banks by purchasing non-voting preferred stock.

I loathed the idea of the government owning pieces of banks. I worried Congress would consider it a bait and switch to spend the money on something other than buying toxic assets. But that was a risk we had to take. The plan for TARP had to change because the financial situation was worsening rapidly. Designing a system to buy mortgage-backed securities would consume time that we didn’t have to spare. Buying shares in banks was faster and more efficient. Purchasing equity would inject capital—the lifeblood of finance—directly into the undercapitalized banking system. That would reduce the risk of sudden failure and free up more money for banks to lend.

Capital injections would also offer more favorable terms for U.S. taxpayers. The banks would pay a 5 percent dividend for the first five years. The dividend would increase to 9 percent over time, creating an incentive for financial institutions to raise less expensive private capital and buy back the preferred shares. The government would also receive stock warrants, which would give us the right to buy shares at low prices in the future. All this made it more likely that taxpayers would get their money back.

On October 13, Columbus Day, Hank, Tim Geithner, and Ben revealed the capital purchase plan in dramatic fashion. They called the CEOs of nine major financial firms to the Treasury Department and told them that, for the good of the country, we expected them to take several billion dollars each. We worried some healthier banks would turn down the capital and stigmatize those who accepted. But Hank was persuasive. They all agreed to take the money.

Deploying TARP had the psychological impact we were hoping for. Combined with a new FDIC guarantee for bank debt, TARP sent an unmistakable signal that we would not let the American financial system fail. The Dow shot up 936 points, the largest single-day increase in stock market history.

TARP didn’t end the financial problems. Over the next three months, Citigroup and Bank of America required additional government funds. AIG continued to deteriorate and eventually needed nearly $100 billion more. The stock market remained highly volatile.

But with TARP in place, banks slowly began to resume lending. Companies began to find the liquidity needed to finance their operations. The panic that had consumed the markets receded. While we knew there was a tough recession ahead, I could feel the pressure ease. I had my first weekend in months without frantic calls about the crisis. Confidence, the foundation of a strong economy, was returning.

The financial crisis was global in scale, and one major decision was how to deal with it in the international arena. The turbulence came during France’s turn as head of the European Union. Nicolas Sarkozy, the dynamic French president who had run on a pro-American platform, urged me to host an international summit. I grew to like the idea. The question was which countries to invite. I heard that some European leaders preferred that we convene the G-7.***** But the G-7 included only about two thirds of the global economy. I decided to make the summit a gathering of the G-20, a group that included China, Russia, Brazil, Mexico, India, Australia, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, and other dynamic economies.

With Nicolas Sarkozy.

I knew it wouldn’t be easy to forge an agreement among the twenty leaders. But with hard work and some gentle arm-twisting, we got it done.****** On November 15, every leader at the summit signed on to a joint statement that read, “Our work will be guided by a shared belief that market principles, open trade and investment regimes, and effectively regulated financial markets foster the dynamism, innovation, and entrepreneurship that are essential for economic growth, employment, and poverty reduction.”

It sent a powerful signal to have countries representing nearly 90 percent of the world economy agree on principles to solve the crisis. Unlike during the Depression, the nations of the world would not turn inward. The framework we established at the Washington summit continues to guide global economic cooperation.

The economic summit was not the biggest event of November. That came on Tuesday, November 4, when Senator Barack Obama was elected president of the United States.

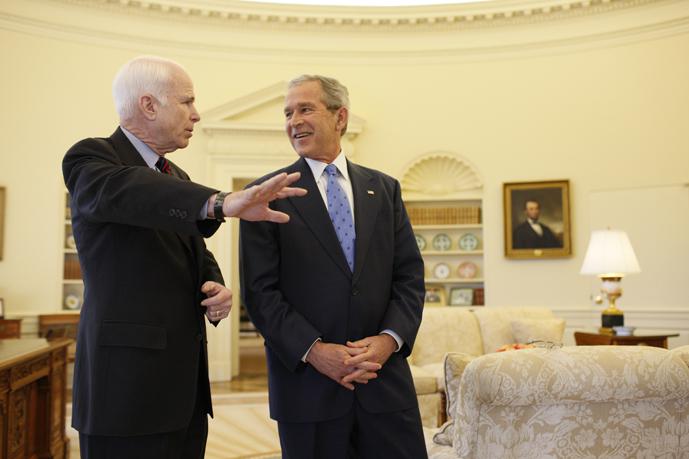

My preference had been John McCain. I believed he was better prepared to assume the Oval Office amid a global war and financial crisis. I didn’t campaign for him, in part because I was busy with the economic situation, but mostly because he didn’t ask. I understood he had to establish his independence. I also suspected he was worried about the polls. I thought it looked defensive for John to distance himself from me. I was confident I could have helped him make his case. But the decision was his. I was disappointed I couldn’t do more to help him.

With John McCain.

The economy wasn’t the only factor working against the Republican candidate. Like Dad in 1992 and Bob Dole in 1996, John McCain was on the wrong side of generational politics. At seventy-two, he was a decade older than I was and one of the oldest presidential nominees ever. Electing him would have meant skipping back a generation. By contrast, forty-seven-year-old Barack Obama represented a generational step forward. He had tremendous appeal to voters under fifty and ran a smart, disciplined, high-tech campaign to get his young supporters to the polls.

As an Obama win looked increasingly likely, I started to think more about what it would mean for an African American to win the presidency. I got an unexpected glimpse a few days before the election. An African American