doubts had shaken him. Later in the day, he sought out Jeb and me. If we were so worried, he asked, why didn’t one of us move to D.C., help in the campaign, and keep an eye on him and the staff?

The invitation intrigued me. The timing was right. After the downturn in the oil markets, my partners and I had merged our exploration company and found jobs for all the employees. Dad liked the idea, and Laura was willing to give it a try.

At the campaign office in downtown Washington, I had no title. As Dad put it, I already had a good one: son. I focused on fundraising, traveling the country to deliver surrogate speeches, and boosting the morale of volunteers by thanking them on Dad’s behalf. From time to time, I also reminded some high-level staffers that they were on a team to advance George Bush’s election, not their own careers. I learned a valuable lesson about Washington: Proximity to power is empowerment. Having Dad’s ear made me effective.

One of my tasks was to sort through journalists’ requests for profile pieces. When Margaret Warner of

Mother called me the morning the magazine hit the newsstands. “Have you seen

I quickly tracked down a copy and was greeted by the screaming headline: “Fighting the Wimp Factor.” I couldn’t believe it. The magazine was insinuating that my father, a World War II bomber pilot, was a wimp. I was red-hot. I got Margaret on the phone. She politely asked what I thought of the story. I impolitely told her I thought she was part of a political ambush. She muttered something about her editors being responsible for the cover. I did not mutter. I railed about editors and hung up. From then on, I was suspicious of political journalists and their unseen editors.

After finishing third in Iowa, Dad rallied with a victory in New Hampshire and went on to earn the nomination. His opponent in the general election was the liberal governor of Massachusetts, Michael Dukakis. Dad started the campaign with a great speech at the convention in New Orleans. I was amazed at the power of his words, elegantly written and forcefully delivered. He spoke of a “kinder, gentler” nation, built by the compassion and generosity of the American people—what he called “a thousand points of light.” He outlined a strong policy agenda, including a bold pledge: “Read my lips, no new taxes.”

I was impressed with Dad’s sense of timing. He had managed to navigate perfectly the transition from loyal vice president to candidate. He left the convention leading the polls and charged down the home stretch. On November 8, 1988, the family watched the returns at our friend Dr. Charles Neblett’s house in Houston. I knew Dad had won when Ohio and New Jersey, two critical states, broke his way. By the end of the night, he had carried forty states and 426 electoral votes. George H.W. Bush, the man I admired and adored, was elected the forty-first president of the United States.

Laura and I enjoyed our year and a half in Washington. But when people suggested that I stay in Washington and leverage my contacts, I never considered it. I had zero interest in being a lobbyist or hanger-on in Dad’s administration. Not long after the election, we packed up for the trip back to Texas.

I had another reason for moving home. Near the end of Dad’s campaign, I received an intriguing phone call from my former business partner Bill DeWitt. Bill’s father had owned the Cincinnati Reds and was well connected in the baseball community. He had heard that Eddie Chiles, the principal owner of the Texas Rangers, was looking to sell the team. Would I be interested in buying? I almost jumped out of my chair. Owning a baseball team would be a dream come true. I was determined to make it happen.

My strategy was to make myself the buyer of choice. Laura and I moved to Dallas, and I visited Eddie and his wife Fran frequently. I promised to be a good steward of the franchise he loved. He said, “You’ve got a great name and a lot of potential. I’d love to sell to you, son, but you don’t have any money.”

I went to work lining up potential investors, mostly friends across the country. When Commissioner Peter Ueberroth argued that we needed more local owners, I went to see a highly successful Fort Worth investor, Richard Rainwater. I had courted Richard before and he had turned me down. This time he was receptive. Richard agreed to raise half the money for the franchise, so long as I raised the other half and agreed to make his friend Rusty Rose co-managing partner.

I went to meet Rusty at Brook Hollow Golf Club in Dallas. He seemed like a shy guy. He had never followed baseball, but he was great with finances. We talked about him being the inside guy who dealt with the numbers, and me being the outside guy who dealt with the public.

Shortly thereafter, Laura and I were at a black-tie charity function. Our plans for the team had leaked out, and a casual acquaintance pulled me aside and whispered: “Do you know that Rusty Rose is crazy? You’d better watch out.” At first I blew this off as mindless chatter. Then I fretted. What did “crazy” mean?

I called Richard and told him what I had heard. He suggested that I ask Rusty myself. That would be a little awkward. I barely knew the guy, and I was supposed to question his mental stability? I saw Rusty at a meeting that afternoon. As soon as I entered the conference room, he walked over to me and said, “I understand you have a problem with my mental state. I see a shrink. I have been sick. What of it?”

It turns out Rusty was not crazy. This was his awkward way of laying out the truth, which was that he suffered from a chemical imbalance that, if not properly treated, could drive his bright mind toward anxiety. I felt so small. I apologized.

Rusty and I went on to build a great friendship. He helped me to understand how depression, an illness I later learned had also afflicted Mother for a time in her life, could be managed with proper care. Two decades later in the Oval Office, I stood with Senators Pete Domenici and Ted Kennedy and signed a bill mandating that insurance companies cover treatment for patients with mental illness. As I did, I thought of my friend Rusty Rose.

With Rusty and Richard as part of our ownership group, we were approved to buy the team.** Eddie Chiles suggested that he introduce us to the fans as the new owners on Opening Day 1989. We walked out of the dugout, across the lush green grass, and onto the pitcher’s mound, where we joined Eddie and legendary Dallas Cowboys coach Tom Landry, who threw out the first pitch. I turned to Rusty and said, “This is as good as it gets.”

Over the next five seasons, Laura and I went to fifty or sixty ball games a year. We saw a lot of wins, endured our fair share of losses, and enjoyed countless hours side by side. We took the girls to spring training and brought them to the park as much as possible. I traveled throughout the Rangers’ market, delivering speeches to sell tickets and talking up the ball club with local media. Over time, I grew more comfortable behind the lectern. I learned how to connect with a crowd and convey a clear message. I also gained valuable experience handling tough questions from journalists, in this case mostly about our shaky pitching rotation.

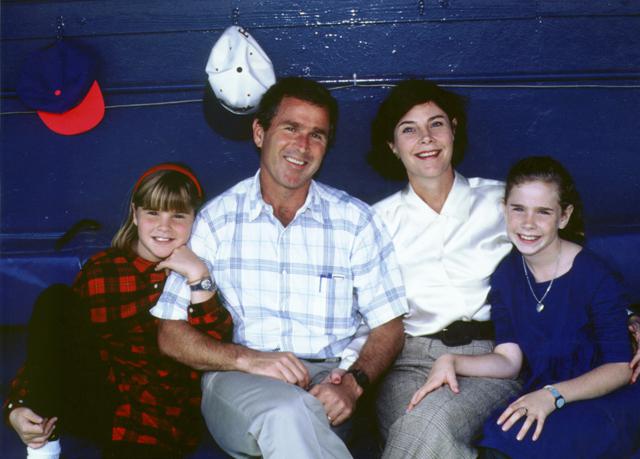

In the Rangers’ dugout with our girls. Owning a ballclub was my dream, and I was certain it was the best job I’d ever have.

Running the Rangers sharpened my management skills. Rusty and I spent our time on the major financial and strategic issues, and left the baseball decisions to baseball men. When people did not perform, we made changes. It wasn’t easy to ask decent folks like Bobby Valentine, a dynamic manager who had become a friend of mine, to move on. But I tried to deliver the news in a thoughtful way, and Bobby handled it like a professional. I was grateful when, years later, I heard him say, “I voted for George W. Bush, even though he fired me.”

When Rusty and I took over, the Rangers had finished with a losing record seven of the previous nine years. The club posted a winning record four of our first five seasons. The improvements on the field brought more people to the stands. Still, the economics of baseball were tough for a small-market team. We never asked the ownership group for more capital, but we never distributed cash, either.

Rusty and I realized the best way to increase the long-term value of the franchise was to upgrade our stadium. The Rangers were a major league team playing in a minor league ballpark. We designed a public-private financing system to fund the construction of a new stadium. I had no objection to a temporary sales tax increase to pay for the park, so long as local citizens had a chance to vote on it. They passed it by a margin of nearly two to one.

Thanks to the leadership of Tom Schieffer—a former Democratic state representative who did such a fine job overseeing the stadium project that I later asked him to serve as ambassador to Australia and Japan—the beautiful new ballpark was ready for Opening Day 1994. Over the following years, millions of Texans came to watch games at the new venue. It was a great feeling of accomplishment to know that I had been part of the management team that made it possible. By then, though, a pennant race wasn’t the only kind I had on my mind.