strength.

I felt for Don again in the spring of 2006, when a group of retired generals launched a barrage of public criticism against him. While I was still considering a personnel change, there was no way I was going to let a group of retired officers bully me into pushing out the civilian secretary of defense. It would have looked like a military coup and would have set a disastrous precedent.

As 2006 wore on, the situation in Iraq worsened dramatically. Sectarian violence was tearing the country apart. In the early fall, Don told me he thought we might need “fresh eyes” on the problem. I agreed that change was needed, especially since I was seriously contemplating a new strategy, the surge. But I was still struggling to find a capable replacement.

One evening in the fall of 2006, I was chatting with my high school and college friend Jack Morrison, whom I had appointed to the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB). I was worried about the deteriorating conditions in Iraq and mentioned Don Rumsfeld’s comment about needing fresh eyes.

“I have an idea,” Jack said. “What about Bob Gates?” He told me he had met with Gates recently as part of his PFIAB work.

Why hadn’t I thought of Bob? He had been CIA director in Dad’s administration and deputy national security adviser to President Reagan. He had successfully run a large organization, Texas A&M University. He served on the Baker-Hamilton Commission, which was studying the problems in Iraq. He would be ideal for the job.

I immediately called Steve Hadley and asked him to feel out Bob. We had tried to recruit him as director of national intelligence the previous year, but he had declined because he loved his job as president of A&M. Steve reported back the next day. Bob was interested.

I was pretty sure I had found the right person for the job. But I was concerned about the timing. We were weeks away from the 2006 midterm elections. If I were to change defense secretaries at that point, it would look like I was making military decisions with politics in mind. I decided to make the move after the election.

The weekend before the midterms, Bob drove from College Station, Texas, to the ranch in Crawford. We met in my office, a secluded one-story building about a half-mile from the main house. I felt comfortable around Bob. He is a straightforward, unassuming man with a quiet strength. I promised him access to me anytime he needed it. Then I told him there was something else he needed to know before taking the job: I was seriously considering a troop increase in Iraq. He was open to it. I told him I knew he had a great life at A&M, but his country needed him. He accepted the job on the spot.

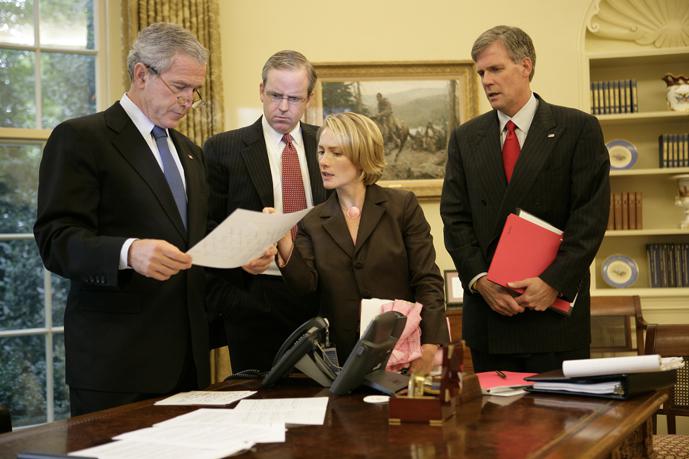

At Camp David with Bob Gates (

I knew Dick would not be happy with my decision. He was a close friend of Don’s. As always, Dick told me what he thought. “I disagree with your decision. I think Don is doing a fine job. But it’s your call. You’re the president.” I asked Dick to deliver the news to his friend, which I hoped would soften the blow.

Don handled the change like the professional he is. He sent me a touching letter. “I leave with great respect for you and for the leadership you have provided during a most challenging time for our country,” he wrote. “… It has been the highest honor of my long life to have been able to serve our country at such a critical time in our history.”

Replacing the secretary of defense was one of two difficult personnel changes I made in 2006. The other was changing chiefs of staff. With the environment in Washington turning sour, Andy Card reminded me often that there were only a handful of positions in which a personnel move would be viewed as significant. His job was one of them. In early 2006, Andy often brought up the possibility of his departure. “You can do it easily and it could change the debate,” he said. “You owe it to yourself to consider it.”

Around the same time, Clay Johnson asked to see me. Clay had served with me every day since I took office as governor in 1995. When we sat down for lunch that day, he asked me how I thought the White House was functioning. I told him I was a little unsettled. I had been hearing complaints from staff members. From the perch of the presidency, though, it was hard to tell whether the gripes were petty grievances or evidence of a serious problem.

Clay gave me a look that showed there wasn’t much doubt in his mind. Then he pulled a pen out of his pocket, picked up his napkin, and sketched the organizational chart of the White House. It was a tangled mess, with lines of authority crossing and blurred. His point was clear: This was a major source of the unrest. Then he said, “I am not the only one who feels this way.” He told me that several people had spontaneously used the same unflattering term to describe the White House structure: It started with “cluster” and ended with four more letters.

Clay was right. The organization was drifting. People had settled into comfort zones, and the sharpness that had once characterized our operation had dulled. The most effective way to fix the problem was to make a change at the top. I decided it was time to take Andy up on his offer to move on.

The realization was painful. Andy Card was a loyal, honorable man who led the White House effectively through trying days. On a trip to Camp David that spring, I went to see Andy and his wife Kathi at the bowling alley. They are one of those great couples whose love for each other is so obvious. They knew I wasn’t there for bowling. My face must have betrayed my anguish. I started by thanking Andy for his service. He cut me off and said, “Mr. President, you want to make a change.” I tried to explain. He wouldn’t let me. We hugged and he said he accepted my decision.

I was uncomfortable creating any large vacancy without having a replacement lined up. So before I had my talk with Andy, I had asked Josh Bolten to come see me. I respected Josh a lot, and so did his colleagues. Since his days as policy director of my campaign, he had served as deputy chief of staff for policy and director of the Office of Management and Budget. He knew my priorities as well as anyone. My trust in him was complete.

When I asked Josh if he would be my next chief of staff, he did not jump at the offer. Like most at the White House, he admired Andy Card and knew how hard the job could be. After thinking about it, he agreed that the White House needed restructuring and refreshing. He told me that if he took the job, he expected a green light to make personnel changes and clarify lines of authority and responsibility. I told him that was precisely why I wanted him. He accepted the job and stayed to the end, which made him one of the first staffers I hired for my campaign and the last I saw in the Oval Office—with ten full years in between.

Shortly after taking over, Josh moved forward with a number of changes, including replacing the White House press secretary with Tony Snow, a witty former TV and radio host who became a dear friend until he lost his valiant battle with cancer in 2008. The trickiest move was redefining Karl’s role. After the 2004 election, Andy had asked Karl to become deputy chief of staff for policy, the top policy position in the White House. I understood his rationale. Karl is more than a political adviser. He is a policy wonk with a passion for knowledge and for turning ideas into action. I approved his promotion because I wanted to benefit from Karl’s expertise and abilities. To avoid any misperceptions, Andy made clear that Karl would not be included in national security meetings.

With my communications team, (

By the middle of 2006, Republicans were in trouble in the upcoming midterm elections, and the left had unfairly used Karl’s new role to accuse us of politicizing policy decisions. Josh asked Karl to focus on the midterms and continue to provide strategic input. To take over the day-to-day policy operations, Josh brought in his deputy from OMB—Joel Kaplan, a brilliant and personable Harvard Law graduate who had worked for me since 2000.

I worried about how Karl would interpret the move. He had developed a thick skin in Washington, but he was a proud, sensitive man who had absorbed savage attacks on my behalf. It was a tribute to Karl’s loyalty and Josh’s managerial skill that they made the new arrangement work until Karl left the White House in August 2007.

While White House staff and Cabinet appointments are crucial to decision making, they are temporary. Judicial appointments are for life. I knew how proud Dad was to have appointed Clarence Thomas, a wise, principled, humane man. I also knew he was disappointed that his other nominee, David Souter, had evolved into a different kind of judge than he expected.

History is full of similar tales. John Adams famously called Chief Justice John Marshall—who served on the bench for thirty years after Adams left office—his greatest gift to the American people. On the other hand, when