told the young ballplayers that day, “I wanted to be the Willie Mays of my generation, but I couldn’t hit a curveball. So, instead, I ended up being president.”

In 1959 my family left Midland and moved 550 miles across the state to Houston. Dad was the CEO of a company in the growing field of offshore drilling, and it made sense for him to be close to his rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. Our new house was in a lush, wooded area that was often pelted by rainstorms. This was the exact opposite of Midland, where the only kind of storm you got was a dust storm. I was nervous about the move, but Houston was an exciting city. I learned to play golf, made new friends, and started at a private school called Kinkaid. At the time, the differences between Midland and Houston seemed big. But they were nothing compared to what was coming next.

One day after school, Mother was waiting at the end of our driveway. I was in the ninth grade, and mothers never came out to meet the bus—at least mine didn’t. She was clearly excited about something. As I got off the bus, she let it out: “Congratulations, George, you’ve been accepted to Andover!” This was good news to her. I wasn’t so sure.

Dad had taken me to see his alma mater, Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, the previous summer. It sure was different from what I was used to. Most of the dorms were large brick buildings arranged around quads. It looked like a college. I liked Kinkaid, but the decision had been made. Andover was a family tradition. I was going.

My first challenge was explaining Andover to my friends in Texas. In those days, most Texans who went away to high school had discipline problems. When I told a friend that I was headed to a boarding school in Massachusetts, he had only one question: “Bush, what did you do wrong?”

When I got to Andover in the fall of 1961, I thought he might be on to something. We wore ties to class, to meals, and to the mandatory church services. In the winter months, we might as well have been in Siberia. As a Texan, I identified four new seasons: icy snow, fresh snow, melting snow, and gray snow. There were no women, aside from those who worked in the library. Over time, they began to look like movie stars to us.

The school was a serious academic challenge. Going to Andover was the hardest thing I did until I ran for president almost forty years later. I was behind the other students academically and had to study like mad. In my first year, the lights in our dorm rooms went out at ten o’clock, and many nights I stayed up reading by the hall light that shined under the door.

I struggled most in English. For one of my first assignments, I wrote about the sadness of losing my sister Robin. I decided I should come up with a better word than

When the paper came back, it had a huge zero on the front. I was stunned and humiliated. I had always made good grades in Texas; this marked my first academic failure. I called my parents and told them I was miserable. They encouraged me to stay. I decided to tough it out. I wasn’t a quitter.

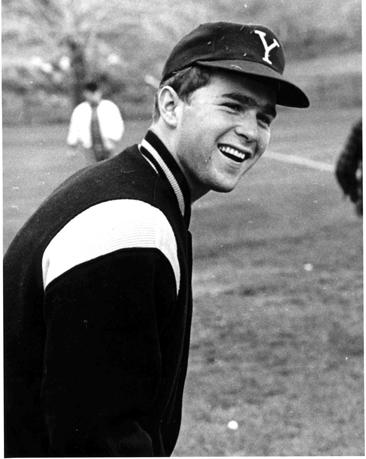

Home in Houston on a break from Andover. Because of the age difference, I felt more like an uncle than a brother to my siblings in those days.

My social adjustment came faster than my academic adjustment. There was a small knot of fellow Texans at Andover, including a fellow from Fort Worth named Clay Johnson. We spoke the same language and became close friends. Soon I broadened my circle. For a guy who was interested in people, Andover was good grazing.

I discovered that I was a natural organizer. My senior year at Andover, I appointed myself commissioner of our stickball league. I called myself Tweeds Bush, a play on the famous New York political boss. I named a cabinet of aides, including a head umpire and a league psychologist. We devised elaborate rules and a play-off system. There was no wild card; I’m a purist.

We also came up with a scheme to print league identification cards, which conveniently could double as fake IDs. The plan was uncovered by school authorities. I was instructed to cease and desist, which I did. In my final act as commissioner, I appointed my successor, my cousin Kevin Rafferty.

That final year at Andover, I had a history teacher named Tom Lyons. He liked to grab our attention by banging one of his crutches on the blackboard. Mr. Lyons had played football at Brown University before he was stricken by polio. He was a powerful example for me. His lectures brought historical figures to life, especially President Franklin Roosevelt. Mr. Lyons loved FDR’s politics, and I suspect he found inspiration in Roosevelt’s triumph over his illness.

Mr. Lyons pushed me hard. He challenged, yet nurtured. He hectored and he praised. He demanded a lot, and thanks to him I discovered a life-long love for history. Decades later, I invited Mr. Lyons to the Oval Office. It was a special moment for me: a student who was making history standing next to the man who had taught it to him so many years ago.

As the days at Andover wound down, it came time to apply to college. My first thought was Yale. After all, I was born there. One time-consuming part of the application was filling out the blue card that asked you to list relatives who were alumni. There was my grandfather and my dad. And all his brothers. And my first cousins. I had to write the names of the second cousins on the back of the card.

Despite my family ties, I doubted I would be accepted. My grades and test scores were respectable but behind many in my class. The Andover dean, G. Grenville Benedict, was a realist. He advised that I “get some good insurance” in case Yale didn’t work out. I applied to another good school, the University of Texas at Austin, and toured the campus with Dad. I started to picture myself there as part of an honors program called Plan Two.

At the mailbox one day, I was stunned to find a thick envelope with a Yale acceptance. Mr. Lyons had written my recommendation, and all I could think was that he must have come up with quite a letter. Clay Johnson opened his admissions letter at the same time. When we agreed to be roommates, the decision was sealed.

Leaving Andover was like ridding myself of a straitjacket. My philosophy in college was the old cliche: work hard, play hard. I upheld the former and excelled at the latter. I joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, played rugby and intramural sports, took road trips to girls’ colleges, and spent a lot of time hanging out with friends.

At Yale.

My boisterous spirit carried me away at times. During my senior year, we were at Princeton for a football game. Inspired by the Yale win—and more than a little booze—I led a group onto the field to tear down the goalposts. The Princeton faithful were not amused. I was sitting atop the crossbar when a security guard pulled me down. I was then marched the length of the field and put in a police car. Yale friends started rocking the car and shouting, “Free Bush!”

Sensing disaster, my friend Roy Austin—a big guy from the island of St. Vincent who was captain of the Yale soccer team—yelled at the crowd to move. Then he jumped into the car with me. When we made it to the police station, we were told to leave campus and never return. All these years later I still haven’t been back to Princeton. As for Roy, he continued to hone his diplomatic skills. Four decades later, I appointed him ambassador to Trinidad and Tobago.

At Yale, I had no interest in being a campus politician. But occasionally I was exposed to the politics of the campus. The fall of my freshman year, Dad ran for the Senate against a Democrat named Ralph Yarborough. Dad got more votes than any Republican candidate in Texas history, but the national landslide led by President Johnson was too much to overcome. Shortly after the election, I introduced myself to the Yale chaplain, William Sloane Coffin. He knew Dad from their time together at Yale, and I thought he might offer a word of comfort. Instead, he told me that my father had been “beaten by a better man.”

His words were a harsh blow for an eighteen-year-old kid. When the story was reported in the newspapers more than thirty years later, Coffin sent me a letter saying he was sorry for the remark, if he had made it. I accepted his apology. But his self-righteous attitude was a foretaste of the vitriol that would emanate from many college professors during my presidency.

Yale was a place where I felt free to discover and follow my passions. My wide range of course selections included Astronomy, City Planning, Prehistoric Archaeology, Masterpieces of Spanish Literature, and, still one of my favorites, Japanese Haiku. I also took a political science course, Mass Communication, which focused on the