Near the back wall of the chamber Driscoll saw movement, a shadow hunched over, sliding along the rock wall. Not moving toward them but somewhere else. Driscoll holstered his pistol, turned to Tait, then pointed at the gomer on the ground

“Grenade!” Driscoll shouted and dropped flat.

Driscoll looked up and around. “Head count!”

“Okay,” Tait replied, followed in quick succession by Young and the others.

The grenade had bounced off the wall and rolled to a stop before the alcove, leaving behind a beach ball-sized crater in the dirt.

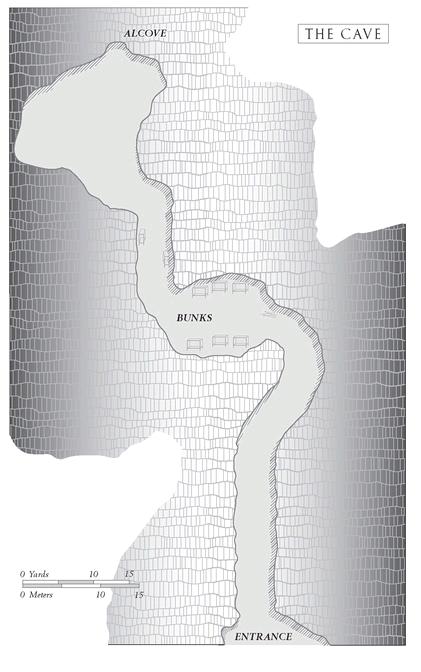

Driscoll took off his PVS-17s and took out his flashlight. This he turned on and played it about. This was the command segment of the cave. Lots of bookshelves, even a rug on the floor of the cave. Most Afghans they’d met were only semiliterate, but there were books and magazines in evidence, some of the latter in English, in fact. One sparsely filled shelf with nicely bound leather-sided books. One in particular… green leather, gold-inlaid. Driscoll flipped it open. An illuminated manuscript, printed-not printed by a machine but by the hand of some long-dead scribe in multicolored ink. This book was old, really old. In Arabic, so it appeared, written by hand and illuminated with gold leaf. This had to be a copy of the Holy Koran, and there was no telling its age or relative value. But it had value. Driscoll took it. Some spook would want to look at it. Back at Kabul they had a couple of Saudis, senior military officers who were backing up the Special Operations people and the Army spooks.

“Okay, Peterson, we’re clear. Code it up and call it in,” Driscoll radioed to his communications specialist. “Target secure. Nine tangos down for the count, two prisoners taken alive. Zero friendly casualties.”

“But nothing under the Christmas tree, Santa,” Sergeant Young said quietly. “Damn, this one felt pretty good coming in. Had the right vibe, I thought.” One more dry hole for the Special Operations troops. They’d drilled too many of those already, but that was the nature of Special Operations.

“Me, too. What’s your name, Gomer?” Driscoll asked Tait’s prisoner. There was no response. The flashbang had really tumbled this bastard’s gyros. He didn’t yet understand that it could have been worse. A whole shitload worse. Then again, once the interrogators got ahold of him…

“All right, guys, let’s clean this hole out. Look for a computer and any electronic stuff. Turn it upside down and inside out. If it looks interesting, bag it. Get somebody in here to take our friend.”

There was a Chinook on short-fuse alert for this mission, and maybe he’d be aboard it in under an hour. Damn, he wanted to hit the Fort Benning NCO club for a glass of Sam Adams, but that wouldn’t be for a couple of days at best.

While the remainder of his team was setting up an overwatch perimeter outside the cave entrance, Young and Tait searched the entrance tunnel, found a few goodies, maps and such, but no obvious jackpot. That was the way with these things, though. Weenies or not, the intel guys could make a meal out of a walnut. A little scrap of paper, a handwritten Koran, a stick figure drawn in purple crayon-the intel guys could sometimes work miracles with that stuff, which was why Driscoll wasn’t taking any chances. Their target hadn’t been here, and that was a goddamned shame, but maybe the shit the gomers had left behind might lead to something else, which in turn could lead to something good. That’s the way it worked, though Driscoll didn’t dwell on that stuff much. Above his pay grade and out of his MOS-military occupational specialty. Give him and the Rangers the mission, let somebody else worry about the hows and whats and whys.

Driscoll walked to the rear of the cave, playing his flashlight around until he reached the alcove the gomer had seemed so keen to frag. It was about the size of a walk-in closet, he now saw, maybe a little bigger, with a low- hanging ceiling. He crouched down and waddled a few feet into the alcove.

“Whatcha got?” Tait said, coming up behind him.

“Sand table and a wooden ammo crate.”

A flat piece of three-fourths-inch-thick plywood, about two meters square to each side, covered in glued-on sand and papier-mache mountains and ridges, scatterings of boxlike buildings here and there. It looked like something in one of those old-time World War Two movies, or a grade-school diorama. Pretty good job, too, not something half-assed you sometimes see with these guys. More often than not the gomers here drew a plan in the dirt, said some prayers, then went at it.

The terrain didn’t look familiar to Driscoll. Could be anywhere, but it sure as hell looked rugged enough to be around here, which didn’t narrow down the possibilities much. No landmarks, either. No buildings, no roads. Driscoll lifted the corner of the table. It was damned heavy, maybe eighty pounds, which solved one of Driscoll’s problems: no way they were going to haul that thing down the mountain. It was a goddamned brick hang glider; at this altitude the wind was a bitch, and they’d either lose the thing in a gust or it would start flapping and give them away. And breaking it up might ruin something of value.

“Okay, take some measurements and some samples, then go see if Smith is done taking shots of the gomers’ faces and photograph the hell out of this thing,” Driscoll ordered. “How many SD cards we got?”

“Six. Four gigs each. Plenty.”

“Good. Multiple shots of everything, highest resolution. Get some extra lights on it, too, and drop something beside for scale.”

“Reno’s got a tape measure.”

“Good. Use it. Plenty of angles and close-ups-the more, the better.” That was the beauty of digital cameras- take as many as you want and delete the bad ones. In this case they’d leave the deleting to the intel folks. “And check every inch for markings.”

Never could tell what was important. A lot would depend on the model’s scale, he suspected. If it was to scale they might be able to plug the measurements into a computer, do a little funky algebra or algorithms or whatever they used, and come up with a match somewhere. Who knew, maybe the papier-mache stuff would turn out to be special or something, made only in some back-alley shop in Kandahar. Stranger shit had happened, and he wasn’t about to give the higher-ups anything to bitch about. They’d be angry enough that their quarry hadn’t been here, but that wasn’t Driscoll’s fault. Pre-mission intelligence, bad or good or otherwise, was beyond a soldier’s control. Still, the old saying in the military, “Shit runs downhill,” was as true as ever, and in this business there was always someone uphill from you, ready to give the shit ball a shove.

“You got it, boss,” Tait said.

“Frag it when you’re done. Might as well finish the job they should have done.”

Tait trotted off.

Driscoll turned his attention to the ammo box, picking it up and carrying it into the entrance tunnel. Inside was a stack of paper about three inches thick-some lined notebook paper covered in Arabic script, some random numbers and doodles-and a large two-sided foldout map. One side was labeled “Sheet Operational Navigation Chart, G-6, Defense Mapping Agency, 1982” and displayed the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region, while the other, held in place with masking tape, was a map of Peshawar torn from a Baedeker’s travel guide.

4

WELCOME TO AMERICAN AIRSPACE, gentlemen,” the copilot announced.