In the dry summer of 1929, the crew of an RAF aircraft took photographs of the site of the important Roman town of Venta Icenorum — ‘the market-place of the Iceni’. The site is about three miles south of Norwich, in Norfolk, next to the church of Caistor St Edmund. When the pictures were developed, a remarkable street-plan could be seen beneath the fields.

Archaeologists began to excavate the area and discovered a large Anglo-Saxon cremation cemetery on the high ground to the south-east. They found several urns containing remains, and one of them yielded an unexpected linguistic prize. Among a pile of sheep knuckle-bones, probably used as pieces for playing a game, was an ankle- bone (or astragalus) from a roe-deer. And on one side of the bone were carved six runic letters. Turning these into the Latin alphabet, we get the word RAIHAN.

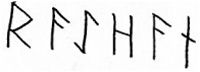

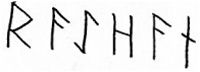

1. The runic letters carved into the surface of the roe deer’s ankle bone found in the Roman town of Caistor-by-Norwich, Norfolk. The shape of the H rune is especially interesting. It has a single cross-bar, which was characteristic of a northern style of writing. Further south, the H was written with two cross-bars. It suggests that the writer may have come from Scandinavia.

1. The runic letters carved into the surface of the roe deer’s ankle bone found in the Roman town of Caistor-by-Norwich, Norfolk. The shape of the H rune is especially interesting. It has a single cross-bar, which was characteristic of a northern style of writing. Further south, the H was written with two cross-bars. It suggests that the writer may have come from Scandinavia. What could it mean? Linguists did a lot of head-scratching. It could be someone’s name. An - n at the end of a word in the Germanic languages of the time sometimes expressed possession — much as ’s does in English today. So perhaps the inscription says Raiha’s or Raiho’s, telling everyone that this piece belonged to him (or her). But a rather more likely explanation is that it names the animal it comes from: the roe-deer, a species that was widespread in northern Europe at the time.

We can plot the history of the word roe. In Old English it appears several times as raha or ra. And it’s seen in some place-names and surnames, such as Rowland (‘roe wood’) in Derbyshire and Roeburn (‘roe stream’) in Lancashire. The vowel changed to an oh sound in the Middle English period. So raihan could mean ‘from a roe’.

Why would anyone write such a thing? It was actually quite a common practice. An object, such as a sheath or a pot, would often display the name of its maker or what it was made of: ‘Edric made me’. ‘Whale’s bone,’ says the runic inscription on one side of the 8th-century Franks Casket. I can’t imagine raihan could mean anything other than ‘roe’, given that it’s written on the only bone in the urn to come from a roe-deer. And if it does mean ‘roe’, then this makes it a candidate for the first discovered word to be written down in the English language.

But is it an English word? The archaeologists dated the find to the 5th century, and it may even be as early as around 400. That would be well before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in 449 — the year we usually think of as marking the start of the Old English period in Britain. The Romans were still in the area then. So maybe the writer was an immigrant who spoke some other language?

There’s evidence that at least some of the settlers in Caistor were from Scandinavia. Several of the urns are very similar to those found in Denmark and the nearby islands. So, imagine such a person settling in Norfolk around the year 400. He would have spoken some sort of early Germanic language, such as Old Norse. But it wouldn’t have taken him long before he started to speak like the people he met in his new surroundings. Settlers have to adapt quickly, if they want to survive. And if he wrote a word down on an object being used in a game — ‘Find the Roe’, perhaps? — then surely it would need to be in a form that the other players would understand.

When we do see ‘roe’ in Old English, a couple of centuries later, it’s spelled with a, not ai. So why did the writer use an i in raihan? It might represent his original language. Or it might be an old-fashioned way of spelling the word he’d picked up in his new language. Or it might genuinely reflect the way he was pronouncing the word at the time. We’ll never know for sure, but my feeling is that the Caistor astragalus, now in the Castle Museum in Norwich, is as close as we can get to the origins of English.

2. Lea — naming places (8th century)

2. Lea — naming places (8th century)

Most people never use the word lea. It’s a poetic word, meaning a grassy meadow. I remember it especially from Thomas Gray’s poem ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’:

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day, The lowing herd winds slowly o’er the lea… I’ve never heard it used on its own outside of poetry. And yet we hear it and see it in a hidden form everywhere in daily life.

Lea is one of the commonest elements to turn up in English place-names. It comes from an Old English word leah (pronounced ‘lay-ah’), meaning an open tract of land, such as a pasture or meadow, natural or man-made. England was heavily forested in Anglo-Saxon times, and it was common practice to make a new settlement by chopping the trees down and starting a farm. If Beorn made a space in this way, it would be called ‘Beorn’s clearing’ — ‘Beorn’s leah’ — modern Barnsley.

The word turns up in many spellings. It’s commonest as ley, but we see it also in such forms as leigh, lee, lees, lease, ly and lay. Sometimes it provides the whole name, as in places called Lea or Leigh. More usually it is just the way the name ends. But if lea is the final element, what does the first element mean?

Often it’s the name of someone, as with Beorn. Someone called Blecca lived in the clearing now covered by modern Bletchley. Dudda lived at Dudley. Wemba lived at Wembley. They are mainly men. Just occasionally we see a woman’s name: Aldgyth lived at Audley. And sometimes a whole tribe lived in the clearing. Madingley means the clearing where Mada’s people lived.

The natural features of the clearing often prompted the name. In Morley the clearing was moorland; in Dingley it was in a dingle. The land must have been level in Evenley, rough in Rowley, stony in Stanley and long-shaped in Langley. Also common is a name where the first part describes the trees that used to grow there, as in Ashley, Oakleigh and Thornley. It can be tricky sometimes to work out what the tree-name is. The birch is hidden in Berkeley, the bramble in Bronley, the yew in Uley and the oak in the strange-looking Acle.

Some lea names refer to what grows in the clearing. It’s obvious what this is in the case of Clover-ley; slightly less obvious in Farleigh (ferns) and Ridley (reeds). And when the farming started, the name sometimes tells us what was grown (as in Wheatley and Flaxley) or what animals were around (as in Durley, Gateley, Horsley and Shipley, for deer, goats, horses and sheep, respectively). Birds and insects are remembered too, in such names as Finchley, Crawley (crows) and Beeleigh.

Place-names are an integral part of a language, and should always be represented in a wordbook. Lea is an example of an Anglo-Saxon place-name element. Other such elements are:

2.

2.