CHAPTER ONE

The man with fourteen days to live is himself witnessing death.

Lincoln (he prefers to go by just his last name. No one calls him “Abe,” which he loathes. Few call him “Mr. President.”

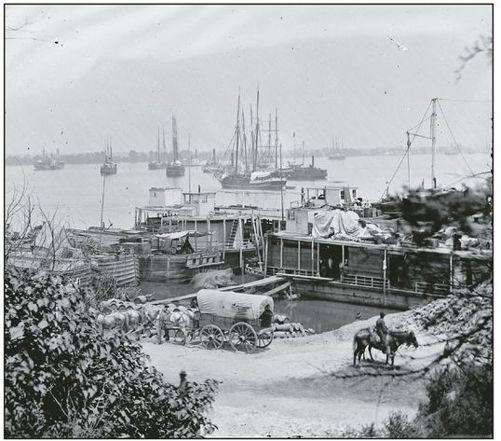

His wife actually calls him “Mr. Lincoln,” and his two personal secretaries playfully refer to him as “the Tycoon”) paces the upper deck of the steamboat River Queen, his face lit now and again by distant artillery. The night air smells of the early spring, damp with a hint of floral fragrance. The

As one Confederate soldier will put it, “the rolling thunder of the heavy metal” began at nine P.M. Once the big guns destroy the Confederate defenses around Petersburg, the Union army—

What happens after that is anyone’s guess.

In a best-case scenario, Lincoln’s general in chief, Ulysses S. Grant, will trap Confederate general Robert E. Lee and his army inside Petersburg, forcing their surrender. This is a long shot. But if it happens, the four-year-old American Civil War will be over, and the United States will be divided no more. And this is why Abraham Lincoln is watching the battlefield.

But Marse Robert—“master” as rendered in southern parlance—has proven himself a formidable opponent time and again. Lee plans to escape and sprint for the North Carolina border to link up with another large rebel force. Lee boasts that his Army of Northern Virginia can hold out forever in the Blue Ridge Mountains, where his men will conceal themselves among the ridges and thickets. There are even bold whispers among the hardcore Confederates about shedding their gray uniforms for plain civilian clothing as they sink undercover to fight guerrilla- style. The Civil War will then drag on for years, a nightmare that torments the president.

Lincoln knows that many citizens of the North have lost their stomach for this war, with its modern technology like repeating rifles and long-range artillery that have brought about staggering losses of life. Anti- Lincoln protests have become more common than the battles themselves. Lee’s escape could guarantee that the northern states rise up and demand that Lincoln fight no more. The Confederates, by default, will win, making the chances of future reunification virtually nonexistent.

Nothing scares Lincoln more. He is so eager to see America healed that he has instructed Grant to offer Lee the most lenient surrender terms possible. There will be no punishment of Confederate soldiers. No confiscation of their horses or personal effects. Just the promise of a hasty return to their families, farms, and stores, where they can once again work in peace.

In his youth on the western frontier, Lincoln was famous for his amazing feats of strength. He once lifted an entire keg of whiskey off the ground, drank from the bung, and then, being a teetotaler, spit the whiskey right back out. An eyewitness swore he saw Lincoln drag a thousand-pound box of stones all by himself. So astonishing was his physique that another man unabashedly described young Abraham Lincoln as “a cross between Venus and Hercules.”

But now Lincoln’s youth has aged into a landscape of fissures and contours, his forehead and sunken cheeks a road map of despair and brooding. Lincoln’s strength, however, is still there, manifested in his passionate belief that the nation must and can be healed. He alone has the power to get it done, if fate will allow him.

Lincoln’s top advisers tell him assassination is not the American way, but he knows he’s a candidate for martyrdom. His guts churn as he stares out into the night and rehashes and second-guesses his thoughts and actions and plans. Last August, Confederate spies had killed forty-three people at City Point by exploding an ammunition barge. Now, at a rail-thin six foot four, with a bearded chin and a nose only a caricaturist could love, Lincoln’s unmistakable silhouette makes him an easy target, should spies once again lurk nearby. But Lincoln is not afraid. He is a man of faith. God will guide him one way or another.

On this night Lincoln calms himself with blunt reality: right now, the most important thing is for Grant to defeat Lee. Surrounded by darkness, alone in the cold, he knows that Grant surrounding Lee and crushing the will of the Confederate army is all that matters.

Lincoln heads to bed long after midnight, once the shelling stops and the night is quiet enough to allow him some peace. He walks belowdecks to his stateroom. He lies down. As so often happens when he stretches out his frame in a normal-sized bed, his feet hang over the end, so he sleeps diagonally.

Lincoln is normally an insomniac on the eve of battle, but he is so tired from the mental strain of what has passed and what is still to come that he falls into a deep dream state. What he sees is so vivid and painful that when he tells his wife and friends about it, ten days later, the description shocks them beyond words.

The dream finally ends as day breaks. Lincoln stretches as he rises from bed, missing his wife back in Washington but also loving the thrill of being so close to the front. He enters a small bathroom, where he stands before a mirror and water basin to shave and wash his hands and face. Lincoln next dons his trademark black suit and scarfs a quick breakfast of hot coffee and a single hard-boiled egg, which he eats while reading a thicket of telegrams from his commanders, including Grant, and from politicians back in Washington.

Then Lincoln walks back up to the top deck of the River Queen and stares off into the distance. With a sigh, he recognizes that there is nothing more he can do right now.

It is April 2, 1865. The man with thirteen days left on earth is pacing.

CHAPTER TWO

There is no North versus South in Petersburg right now. Only Grant versus Lee—and Grant has the upper hand. Lee is the tall, rugged Virginian with the silver beard and regal air.

Grant, forty-two, is sixteen years younger, a small, introspective man who possesses a fondness for cigars and a whisperer’s way with horses. For eleven long months they have tried to outwit one another. But as this Sunday morning descends further and further into chaos, it becomes almost impossible to remember the rationale that has defined their rivalry for so long.

At the heart of it all is Petersburg, a two-hundred-year-old city with rail lines spoking outward in five directions. The Confederate capital at Richmond lies twenty-three miles north—or, in the military definition, based upon the current location of Lee’s army, to the rear.

The standoff began last June, when Grant abruptly abandoned the battlefield at Cold Harbor and wheeled toward Petersburg. In what would go down as one of history’s greatest acts of stealth and logistics, Grant withdrew 115,000 men from their breastworks under cover of darkness and marched them south, crossed the James River without a single loss of life, and then pressed due west to Petersburg. The city was unprotected. A brisk Union