the interminable debate concerning the nature and the significance of the relationship between Russia and the West.

As the examples above, which by no means exhaust the subject, indicate, geography does affect history, Russian history included. It has been noted that the influence of certain geographic factors tends to be especially persistent. Thus, while our modern scientific civilization does much to mitigate

the impact of climate, a fact brilliantly illustrated in the development of such a northern country as Finland, so far we have not changed mountains into plains or created new seas. Still, it is best to conclude with a reservation: geography may set the stage for history; human beings make history.

II

We have only to study more closely than has been done the antiquities of South Russia during the period of migrations, i.e., from the fourth to the eighth century, to become aware of the uninterrupted evolution of Iranian culture in South Russia through these centuries… The Slavonic state of Kiev presents the same features… because the same cultural tradition - I mean the Graeco-Iranian - was the only tradition which was known to South Russia for centuries and which no German or Mongolian invaders were able to destroy.

Yes, we are Scythians. Yes, we are Asiatics. With slanting and greedy eyes.

Continuity is the very stuff of history. Although every historical event is unique, and every sequence of events, therefore, presents flux and change, it is the connection of a given present with its past that makes the present meaningful and enables us to have history. In sociological terms, continuity is indispensable for group culture, without which each new generation of human beings would have had to start from scratch.

A number of ancient cultures developed in the huge territory that was to be enclosed within the boundaries of the U.S.S.R. Those that flourished in Transcaucasia and in Central Asia, however, exercised merely a peripheral influence on Russian history, the areas themselves becoming parts of the Russian state only in the nineteenth century. As an introduction to Russian history proper, we must turn to the northern shore of the Black Sea and to the steppe beyond. These wide expanses remained for centuries on the border of the ancient world of Greece, Rome, and Byzantium. In fact, through the Greek colonies that began to appear in southern Russia from the seventh century before Christ and through commercial and cultural contacts in general, the peoples of the southern Russian steppe participated in classical civilization. Herodotus himself, who lived in the fifth century b.c., spent some time in the Greek colony of Olbia at the mouth of the Bug river and left us a valuable description of the steppe area and its population. Herodotus' account and other scattered and scarce contemporary evidence

have been greatly augmented by excavations pursued first in tsarist Russia and subsequently, on an increased scale, in the Soviet Union. At present we know, at least in broad outline, the historical development of southern Russia before the establishment of the Kievan state. And we have come to appreciate the importance of this background for Russian history.

The best-known neolithic culture in southern Russia evolved in the valleys

of the Dnieper, the Bug, and the Dniester as early as the fourth millennium before Christ. Its remnants testify to the fact that agriculture was then already entrenched in that area, and also to a struggle between the sedentary tillers of the soil and the invading nomads, a recurrent motif in southern Russian, and later Russian, history. This neolithic people also used domestic animals, engaged in weaving, and had a developed religion. The 'pottery of spirals and meander' links it not only to the southern part of Central Europe, but also and especially, as Rostovtzeff insisted, to Asia Minor, although a precise connection is difficult to establish. At about the same time a culture utilizing metal developed in the Kuban valley north of the Caucasian range, contemporaneously with similar cultures in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Its artifacts of copper, gold, and silver, found in numerous burial mounds, testify to the skill and taste of its artisans. While the bronze age in southern Russia is relatively little known and poorly represented, that of iron coincided with, and apparently resulted from, new waves of invasion and the establishment of the first historic peoples in the southern Russian steppe.

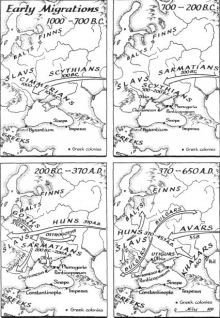

The Cimmerians, about whom our information is very meager, are usually considered to be the earliest such people, again in large part thanks to Herodotus. They belonged to the Thracian subdivision of the Indo-European language family and ruled southern Russia from roughly 1000 B.c. to 700 b.c. At one time their dominion extended deep into the Caucasus. Recent historians have generally assumed that the Cimmerians represented the upper crust in southern Russia, while the bulk of the population consisted of indigenous elements who continued the steady development of culture on the northern shore of the Black Sea. The ruling group was to change several times during the subsequent centuries without destroying this fundamental cultural continuity.

The Scythians followed the Cimmerians, defeating them and destroying their state. The new invaders, who came from Central Asia, spoke an Iranian tongue and belonged thus to the Indo-European language family, although they apparently also included Mongol elements. They ruled southern Russia from the seventh to the end of the third century b.c. The Scythian sway extended, according to a contemporary, Herodotus, from the Danube to the Don and from the northern shore of the Black Sea inland for a distance traveled in the course of a twenty-day journey. At its greatest extent, the Scythian state stretched south of the Danube on its western flank and across the Caucasus and into Asia Minor on its eastern.

The Scythians were typical nomads: they lived in tentlike carriages dragged by oxen and counted their riches by the number of horses, which also served them as food. In war they formed excellent light cavalry, utilizing the saddle and fighting with bows and arrows and short swords. Their military tactics based on mobility and evasion proved so successful that

even their great Iranian rivals, the mighty Persians, could not defeat them in their home territory. The Scythians established a strong military state in southern Russia and for over three centuries gave a considerable degree of stability to that area. Indigenous culture continued to develop, enriched by new contacts and opportunities. In particular, in spite of the nomadic nature of the Scythians themselves, agriculture went on flourishing in the steppe north of the Black Sea. Herodotus who, in accordance with the general practice, referred to the entire population of the area as Scythian, distinguished, among other groups, not only 'the royal Scythians,' but also 'the Scythian ploughmen.'

The Scythians were finally defeated and replaced in southern Russia by the Sarmatians, another wave of Iranian-speaking nomads from Central Asia. The Sarmatian social organization and culture were akin to the Scythian, although some striking differences have been noted. Thus, while both peoples fought typically as cavalry, the Sarmatians used stirrups and armor, lances, and long swords in contrast to the light equipment of the Scythians. What is more important is that they apparently had little difficulty in adapting themselves to their new position as rulers of southern Russia and in fitting into the economy and the culture of the area. The famous Greek geographer Strabo, writing in the first century A.D., mentions this continuity and in particular observes that the great east-west trade route through the southern Russian steppe remained open under the Sarmatians. The Sarmatians were divided into several tribes of which the Alans, it would seem, led in numbers and power. The Ossetians of today, a people living in the central Caucasus, are direct descendants of the Alans. The Sarmatian rule in southern Russia lasted from the end of the third century b.c. to the beginning of the third century a.D.