As with the species of Geese mentioned above, gender differences are also apparent in various behavior types. Of those mammal and bird species in which some form of homosexual behavior occurs, each of the activities of courtship, affectionate, sexual, or pair-bonding are generally more prevalent in male animals. They occur among males in 75—95 percent of the species in which they are found, while among females these activities occur in 50— 70 percent of the species (again, however, the possible gender bias of the studies these figures are based on must be kept in mind). The one exception is same-sex parenting, which is performed by females in more than 80 percent of the species where this behavior occurs, but by males in just over half of the species that have some form of such parenting. Of course, not all these forms of same-sex interaction always co-occur in the same species, and animals sometimes differ as to which activities males as opposed to females of the same species tend to participate in (as in the Geese). In Silver and Herring Gulls, for example, females form same-sex pairs that undertake parenting duties while males engage in homosexual mounting; in Cheetahs and Lions, both sexes engage in sexual activity, but males in each species also develop same-sex pair-bonds while female Cheetahs participate in same-sex courtship activities. In Ruffs, males engage in sexual, courtship, and (occasional) pairing activity with each other, while Reeves (the name for females of this sandpiper species) participate primarily in sexual activity with one another.

Within each of the categories of courtship, sexual, pairing, and parenting behaviors, further gender distinctions can be drawn. Consider various types of sexual behavior. Mounting as a same-sex activity is ubiquitous and occurs fairly regularly in both males and females (although there are exceptions—in African Elephants, for example, sexual activity between males assumes the form of mounting while female same-sex interactions consist of mutual masturbation). Oral sex (which includes activities as diverse as fellatio, cunnilingus, genital nuzzling and sniffing, and beak-genital propulsion) is about equally prevalent in both sexes. Group sexual activity is more common in males (only occurring among females in 6 species, including Bonobos and Sage Grouse), as are interactions between adults and adolescents (only occurring among females in 9 species, including Hanuman Langurs, Japanese Macaques, Ring-billed Gulls, and Jackdaws, but among males in more than 70 species). Although penetration is also more typical of male homosexual interactions, there are notable exceptions (e.g., Bonobos, Orang-utans, and Dolphins, as mentioned previously). Gender differences sometimes also manifest themselves in the minutiae of various sexual acts. Same-sex mounting in Gorillas, for instance, is performed in both face-to-face and front-to-back positions, but the two sexes differ in the frequency with which these two positions are used: females prefer the face-to-face position, adopting it in the majority of their sexual interactions, while males use it less often, in only about 17 percent of their homosexual mounting episodes.23 In contrast, the frequency of full genital contact during homosexual copulations is nearly identical for both sexes of Pukeko: females achieve cloacal contact in about 23 percent of their same-sex mounts while males do so in about 25 percent of theirs (in comparison, genital contact occurs in a third to half of all heterosexual mounts). Among Flamingos, though, genital contact is more characteristic of copulations between females than between males.24

Or consider pair-bonding and parenting. Stable, long-lasting pair-bonds are generally not more characteristic of females (contrary to what one might initially expect); mated pairs or partnerships are almost equally common in both sexes (in terms of number of species in which homosexual pair-bonding occurs), while same-sex companionships are more prevalent between males. Likewise, long-term pair-bonds are just as likely to be found between males as females, while nonmonogamy and divorce occur in male and female couples in roughly equal numbers of species. Nor are male couples less successful parents: male coparents or partners are not overrepresented among the few species in which same-sex parents occasionally experience parenting difficulties. One area where a gender difference in same-sex parenting does manifest itself is in the way that homosexual pairs “acquire” offspring. Particularly among birds, female couples can raise their own offspring by simply having one or both partners mate with males without interrupting their homosexual pair-bond. This option is not as widely available for male couples, who usually father their own offspring by forming a longer-lasting (prior or simultaneous) association with a female (as in Black Swans, Greylag Geese, and Greater Rheas).

Japanese Macaques offer a particularly compelling example of the multiple ways that homosexual activity can differ between males and females. Although homosexual mounting occurs in both sexes in this species, males and females differ in the specific details of their sexual interactions. Homosexual mounts are usually initiated by the mounter between males but by the mountee between females, make use of a wider variety of mounting positions between females, are accompanied by a unique vocalization only between males, and involve pelvic thrusting and multiple mounts more often between females than between males.25 The two sexes also differ in their partner selection and pair-bonding activities: females generally form strongly bonded consortships and have fewer partners than males, while the latter tend to interact sexually with more individuals and develop less intense bonds (although some do have “preferred” male partners). Finally, there is a seasonal difference in male as opposed to female same-sex interactions: homosexual mounting is more common outside the breeding season in males but during the breeding season in females, while same-sex bonds in females, but not males, may extend into yearlong associations that transcend the breeding season.

Whether we’re talking about ganders and geese or Ruffs and Reeves, whether it’s Botos and Bonobos or Pukus and Pukeko, male and female homosexuality can be either surprisingly similar to each other or decidedly distinctive from one another. In any case, a complex intersection of factors is involved in the expression of homosexuality in each gender. As with other aspects of animal homosexuality, preconceived ideas about how males and females act must be reassessed and refined when considering the full range of animal behaviors. In some species such as Silver Gulls, male and female homosexualities conform to stereotypes commonly held about similar human behaviors: females form stable, long-lasting lesbian pair-bonds and raise families while males participate in promiscuous homosexual activity. In other species these gender stereotypes are turned completely on their heads, as in Black Swans, where only males form long-term same-sex couples and raise offspring, and Sage Grouse, where only females engage in group “orgies” of homosexual activity.26 And in the majority of cases, male and female homosexualities present their own unique blends of behaviors and characteristics that defy any simplistic categorization—such as Bonobos, where sexual penetration occurs in female rather than male same-sex activity, where sexual interactions between adults and adolescents are a prominent feature of female interactions, and where males do not form strongly bonded relationships with each other the way females do, but engage in less homosexual activity overall and more affectionate activity such as openmouthed kissing. Once again, the diversity of animal homosexuality reveals itself down to the very last detail of expression.

A Hundred and One Lesbian Acts: Calculating the Frequency of Homosexual Behavior

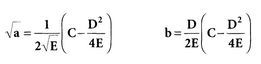

—formulas used in estimating the number of

female homosexual pairs in Gull populations27

While studying Kob antelopes in Uganda, scientists recorded exactly 101 homosexual mounts between females. In Costa Rica, 2 copulations between males were observed during a study of Long-tailed Hermit Hummingbirds. In which species is homosexuality more frequent? The answer would appear to be obvious: Kob. However, simply knowing the total number of homosexual acts observed in each species is not sufficient to evaluate the prevalence of homosexuality. For example, it could be that the Kob were observed for a much longer period of time than the Hummingbirds, in which case the greater number of same-sex mounts would not necessarily reflect any actual difference between the two species. What we really need is a measure of the