where two

A few questions to a couple of villagers elicited the information required. Boniface knocked on the door — painted the ubiquitous blue — of one of the larger buildings, and was directed by the landlord to an annexe at the rear. He ripped aside the goatskin curtain that screened the entrance and stepped inside. Dim light from a small unglazed window revealed, besides domestic clutter, and soldier’s kit hanging from pegs, a cot with a sleeping infant, and a bed containing two figures, one a native woman, the other a huge, fair-haired man. Both sat up and blinked at the intruder.

Boniface rapped, ‘Soldier, she came with you under duress did she not?’ The man shrugged but made no attempt to deny it. To the woman, the general said gently, ‘Tomorrow, you will return with your child to your village, and rejoin your husband. I will arrange an escort.’ To the soldier he said, ‘Get dressed and say farewell. I’ll wait for you outside.’

In silence, Boniface and the soldier marched to a cypress grove a little way beyond the village. Admiring the man’s stoic courage in the calm acceptance of his fate, Boniface drew his sword. .

Attempting to return through the Seldja Gorge in darkness would have been tantamount to suicide, so Boniface took the safe but much longer route round the mountains. Dawn was breaking as he approached camp, and a ghostly radiance shimmered over the pale expanse of the Shott. As the sun’s disc lifted above the horizon, he gazed in wonder as an extraordinary phenomenon developed: an apparent second sun beginning to detach itself from the other. The two orbs separated; the upper rose aloft, the lower wobbled, sank, and deliquesced into the Shott.

An hour later, bathed and shaved, imposing in his parade armour (a splendid though antique suit dating from the time of Alexander Severus, and handed down from father to son through seven generations), Boniface was seated in his command tent, ready to hold tribunal.

First in line was the cuckolded Blemmye.

‘Today, your wife and child return to you,’ the general informed the peasant.

‘And. . the other, lord?’

‘Fear not, my friend, he’ll trouble you no more.’ And with a grim smile, Boniface emptied at the man’s feet the contents of a sack — a severed human head.

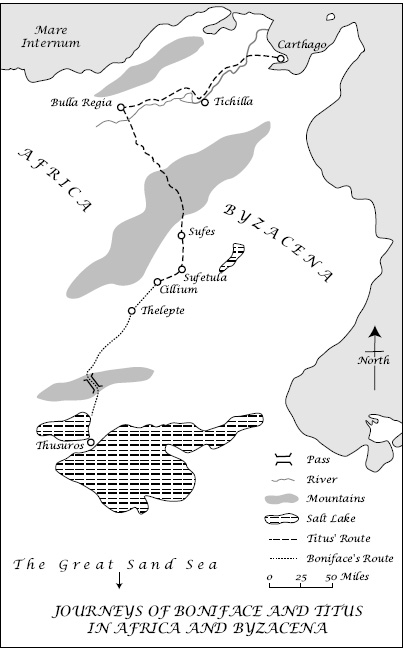

Titus’ ship docked in Carthage’s commercial harbour (warships had their own), overlooked by the capitol on Byrsa Hill. Regretting that time did not permit him to explore the great city, Titus showed his travel warrant at the central post station, and pressed on at a gallop straightway for Bulla Regia as instructed. His route took him south-west along the beautiful valley of the Majerda river wide and flat with extensive vineyards for the first twenty-five miles, after which the terrain became gradually more hilly, terraced vines giving way to olive groves, with broom and terebinth covering slopes too steep for cultivation.

Titus had been born and raised near the border with Gaul, in what had once been the non-Roman territory of Cisalpine Gaul, where his family had been settled for over four hundred years. To Titus Italia proper had always seemed in some ways like a foreign country. Apart from changing horses at a post-station outside the city on his journey to Africa, he had never even been to Rome!

After the flat, misty reclaimed land and small provincial towns of the Po basin, Africa came as a revelation. The brilliant light in which even distant objects stood out sharp and clear; the teeming, cosmopolitan city of Carthage, full of impressive monuments and huge public buildings which seemed almost to be the work of superhuman beings; the staggering fertility — the wheatfields, vineyards and olive groves: all this made a great and lasting impression on the young man. Such evidence (much of it admittedly at least two centuries old) of Rome’s power and far-flung influence almost convinced Titus that the Western Empire was not in serious jeopardy. The barbarians could surely never overthrow a race capable of producing such mighty works. Could they?

After an overnight stop at Tichilla,10 a small town with a postal

When he entered the city, Titus passed a theatre (clearly of recent construction) on his left, then turned right into the main

At the villa, Titus was conducted by a slave through a peristyle, then, to his astonishment, down a flight of steps to a vaulted hallway. This led to a large

‘Cool, even on the hottest days,’ said a languid voice. ‘African summers can be

Titus obeyed.

‘Count Boniface is away on his annual inspection of the central provinces,’ said the president, ‘which suits us decurions — means we can relax a bit and work six instead of twelve hours a day.’ He smiled wryly. ‘Don’t misunderstand me; we all love the Count. It’s just that trying to keep pace with him can be exhausting, to put it mildly. No one takes any liberties when Boniface is around, I assure you. Why, on tour last year, he tracked down one of his own soldiers who’d seduced a native’s wife, and cut the fellow’s head off. What a man!

‘Where is he now? Let me see. He’s due back in Carthage soon, so he’ll probably have finished his sweep of the desert frontier and be heading north. My best advice would be to take the main road south to Sufetula. That way you’ll probably meet him.’

The president’s offer of a bath and a meal was gratefully accepted, and Titus was on his way later that afternoon. He crossed a vast plain where a large river joined the Majerda, after which the terrain rose steadily. By sundown, when he stopped for the night at a lonely mansio, he had reached the foothills of the Dorsale Mountains whose crest delineated the boundary between the provinces of Africa and Byzacena. The following day he pushed on into the mountains (the road looping in most un-Roman fashion to accommodate the gradients), past dense stands of holm oak and Aleppo pines. Crossing the summit ridge in the late afternoon, he found himself in a changed world. Southwards, in the rain-shadow of the mountains, an endless expanse of dusty grassland, sere and yellow as a withered leaf, rolled away to the horizon. A gust of wind like the breath from an oven, fanned his cheek. This, Titus felt, was where the real Africa (the continent as opposed to the province) began. The swift tropical darkness was spreading when he reached his stopover for the night, the little town of Sufes,11 a rustic backwater whose only claim to distinction lay in being another place to have incurred the censure of Augustine. Here, for the first time, he gleaned news of Boniface; the Count was reported to be three days’ march away, at Thelepte, and heading north.

Much encouraged, Titus set off next day at dawn, and after an easy journey of some twenty miles, reached Sufetula, a han some town, completely Roman despite its Punic name. Built on a grid pattern in a striking ochre- coloured stone, it boasted a theatre and amphitheatre, aqueduct, public baths, a cathedral, and no fewer than three