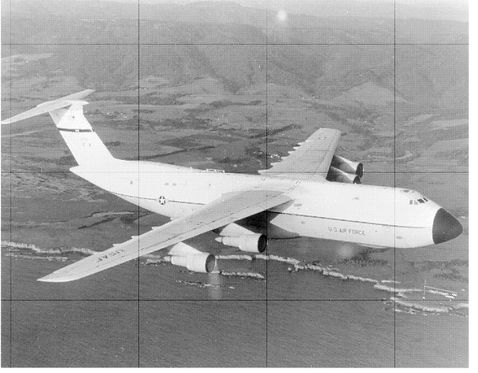

Specifically, they wanted to be able to transport every piece of gear in the Army inventory. This requirement involves what is known as “outsized cargo,” and includes everything from main battle tanks to the Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle (DSRV) submarine used to recover the crews of sunken submarines. Also, America’s experiences during the Cold War of the 1960s were beginning to show a need for being able to rapidly move large conventional units overseas from U.S. bases. The result became the most controversial cargo aircraft of all time; the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy. When it first rolled out of the hanger in Marietta, the C-5 was the largest production aircraft in the world.[4] Everything about this new airlifter was big, from the cargo compartment (at 13.5 feet/4.1 meters high, 19 feet/5.76 meters wide, and 144.5 feet/43.9 meters long, more than big enough to play a regulation basketball game while in flight!) to the landing gear system. It was this massive increase in size over the Starlifter that led to so many of the problems that were to hound the Galaxy for the next few years. On an early test flight, one of the wheels on the main landing gear came loose, careening down the Dobbins AFB runway. There also were structural problems and bugs with the avionics.

These troubles, along with the heavy inflation of the late 1960s and early 1970s, caused severe escalations in the price of the C-5 program. So much so that it nearly bankrupted Lockheed, requiring a costly and controversial bailout loan from the federal government (eventually repaid with interest!) to save the company. While the C-5’s list of problems may have been long, so too was its list of achievements. It proved vital to the evacuation of Vietnam in 1975, despite the loss of one aircraft. By the end of the 1970s, most military and political leaders were wishing that they had bought more Galaxies, whatever the cost. They got their wish later on, thanks to an additional buy of fifty C-5Bs during the early days of the Reagan Administration.

In spite of the obvious worth of the C-5 fleet, though, it was costly to operate and maintain. A single Galaxy can require an aircrew of up to thirteen for certain types of missions, which makes it expensive from a personnel standpoint. Even worse, the C-5 uses huge amounts of fuel, whether it is carrying a full cargo load, or just a few personnel. Finally, Lockheed was never really able to keep its promise to make the C-5 able to take off and land on short, unimproved runways like the C-130. If you talk to Lieutenant General John Keane, the current commander of XVIII Airborne Corps (a primary customer for airlift in the U.S. military), he will lament the shortage of C-5-capable runways around the world. Not that anyone wants to retire the existing Galaxy fleet. Just that any new strategic airlifter would have to do better in these areas than the C-5 or C-141. It would have to be cheaper to operate, crew, and maintain, and would have to combine the C-5’s cargo capacity and range with the C-130’s short-field agility.

This was an ambitious requirement, especially in the tight military budget climate under President Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s. The foreign policy of his Administration was decidedly isolationist, giving the world the impression that America was turning inward and not concerned with the affairs of the rest of the world. This policy came crashing down in 1979, with the storming of the American embassy by “student” militants in Tehran, and the invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviets. Suddenly, there was the feeling in the U.S. that we needed to be able to project power around the world, and to do it quickly. Unfortunately, the drawdown of the U.S. military following Vietnam had left few of the kinds of transportation assets required to do such a job. Clearly the Carter Administration had failed to understand the nature of international relations in the post-Vietnam era, and America’s place in it. The United States would have to work hard to again be credible in the growing disorder that was becoming the world of the 1980s.

Even before Ronald W Reagan became President in 1981, work had started to rebuild America’s ability to rapidly deploy forces overseas. The Navy and Marine Corps quickly began to build up their fleet of fast sealift and maritime prepositioning forces.[5] On the Air Force side came a requirement for a new strategic airlifter which would augment the C-5 in carrying outsized cargo, and eventually replace the aging fleet of C-141 Starlifters. The new airlifter, designated C–X (for Cargo-Experimental), drew on experience the Air Force gained from a technology demonstration program in the mid-1970s. During this program, called the Advanced Medium Short-field Transport (or AMST for short), the USAF had funded a pair of unique technology test beds (the Boeing YC-14 and the McDonnell Douglas YC-15) to try out new ideas for airlift aircraft. Some USAF officials had even hoped that one of the two prototypes might become the basis for a C-130 re-placement.However, the sterling qualities of the “Herky Bird” and the awesome lobbying power of then-Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia dispelled that notion. Instead, the technologies demonstrated by the AMST program were incorporated into the request for proposals for the C–X, which was awarded to Douglas in 1981.

Despite the excellent proposal submitted by Douglas and the best of government intentions, the C–X became a star-crossed aircraft. Delayed by funding problems and the decision to procure additional C-5s first, this new bird seemed at times as if it would never fly. In spite of all this, by the mid- 1980s there was a firm design (now known as the C-17 Globemaster III) on the books, and the first prototype was under construction. The new airlifter was designed to take advantage of a number of new technologies to make it more capable than either the C-141 or C-5. These features included a fly-by-wire flight control system, an advanced “glass” cockpit which replaced gauges and strip indicators with large multi-function displays. The Globemaster also made use of more efficient turbofan engines, advanced composite structures, and a cockpit/crew station design that only requires three crew members (two pilots and a crew chief). The key to the C-17’s performance, though, was the use of specially “blown” flaps to achieve the short-field takeoff-and-landing performance of the C-130. By directing the engine exhaust across a special set of large flap panels, a great deal of lift is generated, thus lowering the stall speed of the aircraft. In a much smaller package which can be operated and maintained at a much lower cost than the C-141 or C-5, the Douglas engineers have given the nation an aircraft that can do everything that the earlier aircraft could do, and more.

Along with the building of the C-17 force, the Air Force is updating the inter-theater transport force built around early versions of the C-130, especially the older C-130E and — F models. Naturally, the answer is another version of the Hercules! The new C-130J is more than a minor improvement over the previous models of this classic aircraft, though. By marrying up the same kind of advanced avionics found on the C-17 with improved engines and the proven Hercules airframe, Lockheed has come up with the premier inter-theater transport for the early 21st century. Already, the Royal Air Force (RAF), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), and the U.S. Air Force (USAF) have signed up to buy the new Hercules, with more buyers already in the wings. This means that there will easily be versions coming off the line in 2004, when the C-130 celebrates its fiftieth year of continuous production!

One other aspect of deploying personnel and equipment by air that we also need to consider is airborne refueling. Ever since a group of Army Air Corps daredevils (including Carl “Tooey” Spatz and several other future Air Force leaders) managed to stay aloft for a number of days by passing a fuel hose from one aircraft to another, aerial refueling has been a factor in air operations. Air-to-air refueling came into its own over Vietnam, where it became a cornerstone of daily operations for aircraft bombing the North. Later on, in the 1970s, in-flight refueling of C-5s and C-141s became common. This was especially true during the October 1973 Arab-Israeli War, when a number of European countries would not allow U.S. cargo aircraft to land and refuel. This meant that tankers based along the way had to refuel the big cargo jets so that they would be able to make their deliveries of cargo into Ben-Gurion Airport nonstop. Today, Air Force cargo flights utilizing air-to-air refueling are commonplace, but then it was cause to rethink the whole problem of worldwide deployment of U.S. forces.

For much of the past thirty years, the bulk of the USAF in-flight refueling duties has been handled by the