Ariana Franklin

Mistress of the Art of Death

The first book in the Mistress of the Art of Death series, 2007

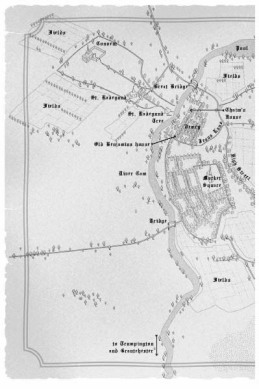

Frontmatter map by Red Lion

TO HELEN HELLER,

MISTRESS OF THE ART OF THRILLERS

One

ENGLAND, 1171

Here they come. From down the road we can hear harnesses jingling and see dust rising into the warm spring sky.

Pilgrims returning after Easter in Canterbury. Tokens of the mitered, martyred Saint Thomas are pinned to cloaks and hats-the Canterbury monks must be raking it in.

They’re a pleasant interruption in the traffic of carts whose drivers and oxen are surly with fatigue from plowing and sowing. These people are well fed, noisy, exultant with the grace their journey has gained them.

But one of them, as exuberant as the rest, is a murderer of children. God’s grace will not extend to a child-killer.

The woman at the front of the procession-a big woman on a big roan mare-has a silver token pinned to her wimple. We know her. She’s the prioress of Saint Radegund’s nunnery in Cambridge. She’s talking. Loudly. Her accompanying nun, on a docile palfrey, is silent and has been able to afford only Thomas a Becket in pewter.

The tall knight riding between them on a well-controlled charger-he wears a tabard over his mail with a cross showing that he’s been on crusade, and, like the prioress, he’s laid out on silver- makes sotto voce commentaries on the prioress’s pronouncements. The prioress doesn’t hear them, but they cause the young nun to smile. Nervously.

Behind this group is a flat cart drawn by mules. The cart carries a single object; rectangular, somewhat small for the space it occupies-the knight and squire seem to be guarding it. It’s covered by a cloth with armorial bearings. The jiggling of the cart is dislodging the cloth, revealing a corner of carved gold-either a large reliquary or a small coffin. The squire leans from his horse and pulls the cloth straight so that the object is hidden again.

And here’s a king’s officer. Jovial enough, large, overweight for his age, dressed like a civilian, but you can tell. For one thing, his servant is wearing the royal tabard embroidered with the Angevin leopards and, for another, poking out of his overloaded saddlebag is an abacus and the sharp end of a pair of money scales.

Apart from the servant, he rides alone. Nobody likes a tax gatherer.

Now then, here’s a prior. We know him, too, from the violet rochet he wears, as do all canons of Saint Augustine.

Important. Prior Geoffrey of Saint Augustine’s, Barnwell, the monastery that looks across the great bend of the River Cam opposite Saint Radegund’s and dwarfs it. It is understood that he and the prioress don’t get on. He has three monks in attendance, and also a knight-another crusader, judging from his tabard-and a squire.

Oh, he’s ill. He should be at the procession’s front, but it seems his guts-which are considerable-are giving him pain. He’s groaning and ignoring a tonsured cleric who’s trying to engage his attention. Poor man, there’s no help for him on this stretch, not even an inn, until he reaches his own infirmary in the priory grounds.

A beef-faced citizen and his wife, both showing concern for the prior and giving advice to his monks. A minstrel, singing to a lute. Behind him there’s a huntsman with spears and dogs-hounds colored like the English weather.

Here come the pack mules and the other servants. Usual riffraff.

Ah, now. At the extreme end of the procession. More riffraffish than the rest. A covered cart with colored cabalistic signs on its canvas. Two men on the driving bench, one big, one small, both dark-skinned, the larger with a Moor’s headdress wound round his head and cheeks. Quack medicine peddlers, probably.

And sitting on the tailboard, beskirted legs dangling like a peasant, a woman. She’s looking about her with a furious interest. Her eyes regard a tree, a patch of grass, with interrogation: What’s your name? What are you good for? If not, why not? Like a magister in court. Or an idiot.

On the wide verge between us and all these people (even on the Great North Road, even in this year of 1171, no tree shall grow less than a bowshot’s distance from the road, in case it give shelter to robbers) stands a small wayside shrine, the usual home-carpentered shelter for the Virgin.

Some of the riders prepare to pass by with a bow and a Hail Mary, but the prioress makes a show of calling for a groom to help her dismount. She lumbers over the grass to kneel and pray. Loudly.

One by one and somewhat reluctantly, all the others join her. Prior Geoffrey rolls his eyes and groans as he’s assisted off his horse.

Even the three from the cart have dismounted and are on their knees, though, unseen at the back, the darker of the men seems to be directing his prayers toward the east. God help us all- Saracens and others of the ungodly are allowed to roam the highways of Henry II without sanction.

Lips mutter to the saint; hands weave an invisible cross. God is surely weeping, yet He allows the hands that have rent innocent flesh to remain unstained.

Mounted again, the cavalcade moves on, takes the turning to Cambridge, its diminishing chatter leaving us to the rumble of the harvest carts and the twitter of birdsong.

But we have a skein in our hands now, a thread that will lead us to that killer of children. To unravel it, though, we must first follow it backward in time by twelve months…

…TO THE YEAR 1170. A screaming year. A king screamed to be rid of his archbishop. Monks of Canterbury screamed as knights spilled the brains of said archbishop onto the stones of his cathedral.

The Pope screamed for said king’s penance. The English Church screamed in triumph-now it had said king where it wanted him.

And, far away in Cambridgeshire, a child screamed. A tiny, tinny sound, this one, but it would reach its place among the others.

At first the scream had hope in it. It’s a come-and-get-me-I’m-frightened signal. Until now, adults had kept the child from danger, hoisted him away from beehives and bubbling pots and the blacksmith’s fire. They

At the sound, deer grazing on the moonlit grass lifted their heads and stared-but it was not one of their own young in fear; they went on grazing. A fox paused in its trot, one paw raised, to listen and judge the threat to itself.

The throat that issued the scream was too small and the place too deeply isolated to reach human help. The scream changed; it became unbelieving, so high on the scale of astonishment that it achieved the pitch of a huntsman’s whistle directing his dogs.

The deer ran, scattering among the trees, their white scuts like dominoes tumbling into the darkness.

The scream was pleading now, perhaps to the torturer, perhaps to God,

The air was grateful when eventually the child fell silent and the usual night noises took over again; a breeze rustling through bushes, the grunt of a badger, the hundred screams of small mammals and birds as they died in the mouths of natural predators.

AT DOVER, an old man was being hurried through the castle at a rate not congenial to his rheumatism. It was a huge castle, very cold and echoing with furious noises. Despite the rate he had to go, the old man remained chilled-partly because he was frightened. The court sergeant was taking him to a man who frightened everybody.

They went along stone corridors, sometimes past open doors issuing light and warmth, chatter and the notes of a lyre, past others that were closed on what the old man imagined to be ungodly scenes.

Their progress sent castle servants cowering or flung them out of the way so that the two of them left behind them a trail of dropped trays, spattered piss pots, and bitten-off exclamations of hurt.

One final circular staircase and they were in a long gallery of which this end was taken up by desks lining the walls and a massive table with a top of green felt partitioned into squares. There were varying piles of counters on the squares. Thirty or so clerks filled the room with the scratch of quills on parchment. Colored balls flicked and clicked along the wires of their abaci so that it was like entering a field of industrious crickets.

In the whole place, the only human being at rest was a man sitting on one of the windowsills.

“Aaron of Lincoln, my lord,” the sergeant announced.

Aaron of Lincoln went down on one painful knee and touched his forehead with the fingers of his right hand, then extended the palm in obeisance to the man on the windowsill.

“Do you know what that is?”

Aaron glanced awkwardly behind him at the vast table and didn’t answer; he knew what it was, but Henry II’s question had been rhetorical.

“It ain’t for playing billiards, I’ll tell you that,” the king said. “It’s my Exchequer. Those squares represent my English counties, and the counters on them show how much income from each is due to the Royal Treasury. Get up.”