Stanislaw Lem

THE CYBERIAD

Translated from the Polish by Michael Kandel

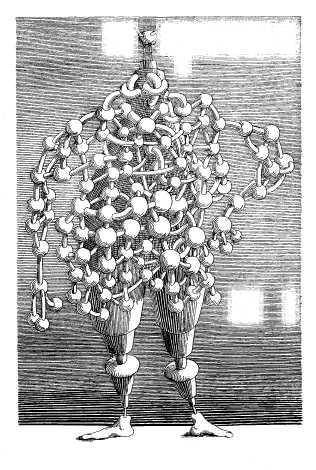

Illustrated by Daniel Mroz

HOW THE WORLD WAS SAVED

One day Trurl the constructor put together a machine that could create anything starting with

“Never heard of it,” said the machine.

“What? But it’s only sodium. You know, the metal, the element…”

“Sodium starts with an

“But in Latin it’s

“Look, old boy,” said the machine, “if I could do everything starting with

“Very well,” said Trurl and ordered it to make Night, which it made at once—small perhaps, but perfectly nocturnal. Only then did Trurl invite over his friend Klapaucius the constructor, and introduced him to the machine, praising its extraordinary skill at such length, that Klapaucius grew annoyed and inquired whether he too might not test the machine.

“Be my guest,” said Trurl. “But it has to start with

“

The machine whined, and in a trice Trurl’s front yard was packed with naturalists. They argued, each publishing heavy volumes, which the others tore to pieces; in the distance one could see flaming pyres, on which martyrs to Nature were sizzling; there was thunder, and strange mushroom-shaped columns of smoke rose up; everyone talked at once, no one listened, and there were all sorts of memoranda, appeals, subpoenas and other documents, while off to the side sat a few old men, feverishly scribbling on scraps of paper.

“Not bad, eh?” said Trurl with pride. “Nature to a T, admit it!”

But Klapaucius wasn’t satisfied.

“What, that mob? Surely you’re not going to tell me that’s Nature?”

“Then give the machine something else,” snapped Trurl. “Whatever you like.” For a moment Klapaucius was at a loss for what to ask. But after a little thought he declared that he would put two more tasks to the machine; if it could fulfill them, he would admit that it was all Trurl said it was. Trurl agreed to this, whereupon Klapaucius requested Negative.

“Negative?!” cried Trurl. “What on earth is Negative?”

“The opposite of positive, of course,” Klapaucius coolly replied. “Negative attitudes, the negative of a picture, for example. Now don’t try to pretend you never heard of Negative. All right, machine, get to work!”

The machine, however, had already begun. First it manufactured antiprotons, then antielectrons, antineutrons, antineutrinos, and labored on, until from out of all this antimatter an antiworld took shape, glowing like a ghostly cloud above their heads.

“H’m,” muttered Klapaucius, displeased. “That’s supposed to be Negative? Well… let’s say it is, for the sake of peace.… But now here’s the third command: Machine, do Nothing!”

The machine sat still. Klapaucius rubbed his hands in triumph, but Trurl said:

“Well, what did you expect? You asked it to do nothing, and it’s doing nothing.”

“Correction: I asked it to do Nothing, but it’s doing nothing.”

“Nothing is nothing!”

“Come, come. It was supposed to do Nothing, but it hasn’t done anything, and therefore I’ve won. For Nothing, my dear and clever colleague, is not your run-of-the-mill nothing, the result of idleness and inactivity, but dynamic, aggressive Nothingness, that is to say, perfect, unique, ubiquitous, in other words Nonexistence, ultimate and supreme, in its very own nonperson!”

“You’re confusing the machine!” cried Trurl. But suddenly its metallic voice rang out:

“Really, how can you two bicker at a time like this? Oh yes, I know what Nothing is, and Nothingness, Nonexistence, Nonentity, Negation, Nullity and Nihility, since all these come under the heading of

The constructors froze, forgetting their quarrel, for the machine was in actual fact doing Nothing, and it did it in this fashion: one by one, various things were removed from the world, and the things, thus removed, ceased to exist, as if they had never been. The machine had already disposed of nolars, nightzebs, nocs, necs, nallyrakers, neotremes and nonmalrigers. At moments, though, it seemed that instead of reducing, diminishing and subtracting, the machine was increasing, enhancing and adding, since it liquidated, in turn: nonconformists, nonentities, nonsense, nonsupport, nearsightedness, narrowmindedness, naughtiness, neglect, nausea, necrophilia and nepotism. But after a while the world very definitely began to thin out around Trurl and Klapaucius.

“Omigosh!” said Trurl. “If only nothing bad comes out of all this…”

“Don’t worry,” said Klapaucius. “You can see it’s not producing Universal Nothingness, but only causing the absence of whatever starts with n. Which is really nothing in the way of nothing, and nothing is what your machine, dear Trurl, is worth!”

“Do not be deceived,” replied the machine. “I’ve begun, it’s true, with everything in

“But—” Klapaucius was about to protest, but noticed, just then, that a number of things were indeed disappearing, and not merely those that started with n. The constructors were no longer surrounded by the gruncheons, the targalisks, the shupops, the calinatifacts, the thists, worches and pritons.

“Stop! I take it all back! Desist! Whoa! Don’t do Nothing!!” screamed Klapaucius. But before the machine could come to a full stop, all the brashations, plusters, laries and zits had vanished away. Now the machine stood motionless. The world was a dreadful sight. The sky had particularly suffered: there were only a few, isolated points of light in the heavens—no trace of the glorious worches and zits that had, till now, graced the horizon!

“Great Gauss!” cried Klapaucius. “And where are the gruncheons? Where my dear, favorite pritons? Where now the gentle zits?!”

“They no longer are, nor ever will exist again,” the machine said calmly. “I executed, or rather only began to execute, your order…”

“I tell you to do Nothing, and you… you…”

“Klapaucius, don’t pretend to be a greater idiot than you are,” said the machine. “Had I made Nothing outright, in one fell swoop, everything would have ceased to exist, and that includes Trurl, the sky, the Universe, and you—and even myself. In which case who could say and to whom could it be said that the order was carried out and I am an efficient and capable machine? And if no one could say it to no one, in what way then could I, who also would not be, be vindicated?”