they've made and their revelations of the personal, social, and theoretical contexts out of which particular works developed can be of considerable interest and use to the viewer trying to come to terms with difficult films. Further, discussions with filmmakers usually reveal the degree to which the critical edge of particular films is the result of conscious decisions by filmmakers interested in cinematically confronting the conventional and to what degree it is a projection by programmers or teachers interested in mining the intertextual potential of the films. And finally, in- depth interviews with filmmakers over several years help to develop a sense of the ongoing history of independent filmmaking and the people and institutions that sustain it.

Volume 2 of

extends the general approach initiated in Volume 1. All the filmmakers interviewed for this volume could be categorized in terms of how fully or how minimally they invoke the conventional cinema and the system of expectations it has created, or to be

Page 4

more precisesince nearly all the filmmakers I interview make various types of filmseach film discussed in this volume could be ranged along an axis that extends from films that invoke many conventionsfilms like James Benning's

(1976), Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen's

(1977), Lizzie Borden's

(1986), and Su Friedrich's

(1987)only to undercut the expectations they've created, to films that seem to have almost no connection with the conventional cinema, but nevertheless explore a dimension of the film experience that underlies both conventional and alternative film practice: Anthony McCall's

(1973), which focuses on the cone of light between projector and wall, is a good example.

My method as an interviewer has also remained the same. I have sought out filmmakers whose work challenges the conventional cinema, whose films pose problems for viewers. Whenever it has seemed both necessary and possible, I have explored all the films of a filmmaker in detail and have discussed them, one by one, in as much depth as has seemed useful. In a few recent instances, however, my interest in interviewing a filmmaker has been spurted by the accomplishments of a single film. I interviewed Anne Severson (now Alice Anne Parker) about

(1972) and Laura Mulvey about

because of the excitement of using these films in classes and the many questions raised about them in class discussions. In most cases, I have traveled to filmmakers' homes or mutually agreed-upon locations and have taped our discussions, subsequently transcribing and editing the discussions and returning them to the filmmakers for corrections. My editing of the transcribed tapes is usually quite extensive: the goal is always to remain as true to the fundamental ideas and attitudes of filmmakers as possible, not simply to present their spoken statements verbatim, though I do attempt to provide a flavor of each filmmaker's way of speaking. The interviews in

are in no instance conceived as exposes; they are attempts to facilitate a communication to actual and potential viewers of what the filmmakers would like viewers to understand about their work, in words they are comfortable with.

While my general approach as an interviewer has remained the same, the implicit structure of Volume 2 differs from that of Volume 1, in which the interviews are arranged roughly in the order I conducted and completed them. In Volume 2 the arrangement of the interviews has nothing to do with the order in which they were conducted. Rather, the volume is organized so as to suggest general historical dimensions of the film careers explored in the interviews and to highlight the potential of the work of individual independent filmmakers not only to critique the conventional cinema but to function within an ongoing discourse with the work of other critical filmmakers.

Page 5

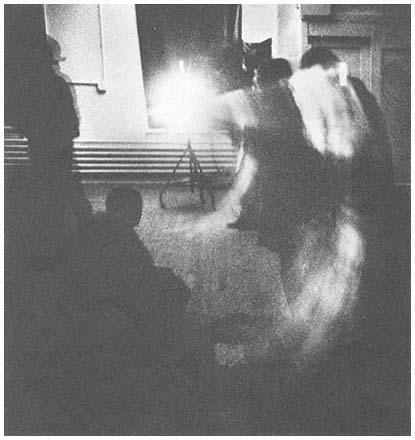

The audience investigates the projector beam during McCall's

(1973).

In general, the interviews collected here provide a chronological overview of independent filmmaking since 1950, especially in North America. The first three intervieweesRobert Breer, Michael Snow, Jonas Mekasmdiscuss developments from the early fifties and conclude in the late seventies (Mekas), the early eighties (Breer), and 1990 (Snow). The next two intervieweesBruce Baillie, Yoko Onoreview developments beginning in the late fifties (Baillie) and early sixties (Ono). Anthony McCall and Andrew Noren discuss their emergence as filmmakers in the early seventies and the mid sixties, respectively. The Anne Robertson and James Benning interviews begin in the mid seventies and end very recently. And so on.

Page 6

Another historical trajectory implicit in the order of the eighteen interviews has to do with the types of critique developed from one decade to the next. Of course, the complexity of the history of North American independent cinema makes any simple chronology of ap- proaches impossible. Indeed, each decade of independent film production has been characterized by the simultaneous development of widely varying forms of critique. And yet, having said this, I would also argue that certain general changes in focus are discernible. One of these is the increasingly explicit political engagement of filmmakers. The films of Breer and Snow emphasize fundamental issues of perception, especially film perception. From time to time, one of their,' films reveals evidence of the filmmaker's awareness of the larger social/political developments of which their work is inevitably a part, but 'in general they focus on the cinematic worlds 'created by their films. The focus of the films of Mekas, Baillie, Ono, and McCall is