Dakota Meyer

INTO THE FIRE

The battle of Ganjigal resulted in the largest loss of American advisors, the highest number of distinguished awards for valor, and the most controversial investigations for dereliction of duty in the entire Afghanistan war. This is the story of a man who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery in that battle.

Introduction

ALONG THE AFGHAN-PAKISTAN BORDER

Lt. Mike Johnson, our team leader, leaned his head way back next to my knees and shouted up the turret hole to me:

“We’re gonna love it here! Look at those mountains, Meyer! Heavy stuff! Let’s go hiking!”

He was yelling over the diesel grind of our Humvee’s engine, the deep drumming of our heavy iron suspension, and the clatter of the gun turret, as I cranked the .50-cal back and forth, chasing my suspicions around the landscape from one likely ambush spot to the next. To man the machine gun atop a Humvee, you stand up through a hole in the roof. Your legs are behind the guys in the front seat.

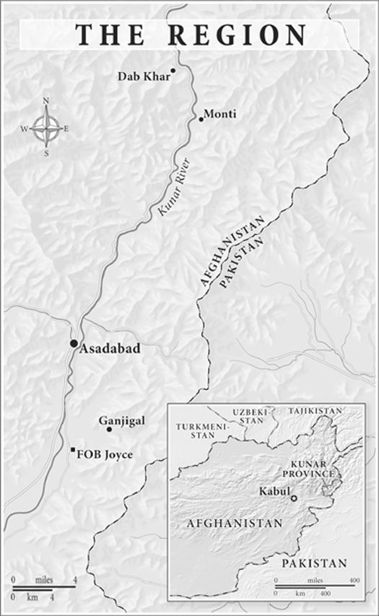

We were roaring through the steep valleys of the Hindu Kush. The Khyber Pass was to the southeast of us— the famed route from the Western world into Pakistan and then India. We were heading north, away from the Khyber, along a river road you wouldn’t want to travel without us. Convoys like ours often get rained on by bullets and RPG shells—rocket-propelled grenades. The local drivers of the big civilian trucks will then panic— understandable—and swerve and crash into each other and tip over and catch on fire and block the narrow highway.

The lieutenant and I had become friends during our weeks of training in California’s High Sierras. He’d try to beat me to the top of a ridge at the end of each day. Then we’d build a lean-to for the night, boil our ramen rice noodles, and sleep under a zillion stars. You couldn’t beat his enthusiasm.

His specialty was communications. Riding now in the Humvee’s shotgun seat, he had control of two radios stacked one on top of the other: one for the convoy and one in contact with the command post, which was ten miles back. So he was paying attention to all that and to the risks around us, and, as usual, said something funny to lighten us up, which makes you more alert. Fear slows down your logic circuits, gives you tunnel vision, and triples your heart rate, which isn’t helpful in modern combat. A good leader keeps you from getting too scared.

I scanned the bleak ridgelines, the big boulders and small caves, scrawny trees and thorny underbrush, all offering cover for snipers. You look for movement or a reflection. Gone were the stands of soaring green fir trees I’d seen in postcards at the airport. I would soon learn that a common English word that had made it into the Pashto language was

“I’m telling you, Meyer,” Johnson said, “I’m going to be a forest ranger and live the good life.”

More likely he’d wind up in Silicon Valley, not hidden away in some wilderness, I thought. He was the only married man on our team and had been living on Okinawa with his wife. Truthfully, I couldn’t figure out why he had volunteered to be an advisor in the first place. The Afghan Army used Radio Shack-type handheld radios, far below his technical skills. He had mentioned Marine traditions in his family. Being a leader was one of them.

Staff Sgt. Aaron Kenefick was our staff NCO (noncommissioned officer). The way it works is your lieutenant, which in our case was Lt. Johnson, is your leader. Your staff NCO is more the administrator. Staff Sgt. Kenefick was the old man at age thirty, and considered himself the ramrod of our outfit. I had sized him up as your typical platoon sergeant, serious, squared-away, and by-the-book. A true New Yorker, he loved his Yankees and kidded me about my Kentucky accent, which isn’t an accent at all but just the way real Americans talk.

Our Navy corpsman was “Doc” Layton, more formally Hospital Man 3rd Class James Layton. As a twenty- two-year-old “boot” (what you’re called on your first tour), he kept his medical supplies in meticulous order, according to him anyway, and his mouth shut when he was around Marine veterans. Inside our little team, though, he was laid-back and droll, a classic California surfer dude.

As for me, I was the only grunt on the team, the infantryman and the weapons trainer. I wasn’t there to train the other three members of my team, but the Afghan soldiers we were on our way to meet. All four of us were coming in as advisors in our areas of specialty. My desire to see action was a running joke. For my twenty-first birthday, Staff Sgt. Kenefick and Lt. Johnson had presented me with a cake that consisted of a piece of bread with a smoking cigarette on top. The others were looking to do their jobs and return home; I was looking for a fight.

We were rolling alongside the Kunar River now, nearing Combat Outpost Monti, the mountain ranges on each side looking like the black skeletons of two massive dinosaurs. We drove past valley after valley, steep cuts carved into the mountains by thousands of years of rain, earthquakes, and erosion, each one occupied by a small, illiterate tribe.

My town in Kentucky is surrounded by gentle hills, rich in grass and water. Our tractor blades cut easily through the topsoil. Still, we know the grind of farm work; the animals and crops don’t take care of themselves. Farming communities work hard, share a bond with the land, and stick together. One long look at those hollows and the stone homes clustered back in the hills told me all I needed to know about the people we were dealing with. It takes plain stubbornness to hack a living out of that flinty earth. If the villagers supported the insurgents, we were in for a long war.

We drove past a few rugged-looking guys with beards and long sticks, beating their sheep off the road. When I waved, they refused to wave back. The tribes, we had learned, lived by the three rules of the Pashtunwali code: courage, hospitality to strangers, and revenge for personal slights. Tough guys. Since the 1930s, the tribes in Kunar had rebelled seven times against the central government. The Russians in the late 1980s never subdued Kunar. In 2001, Osama bin Laden escaped into Pakistan by way of Kunar. A wild place.

“Why’s it called Monti?” I called down to Staff Sgt. Kenefick, who was seated just behind my legs.

“Three or four years ago,” he called back, “there was a big firefight. Some Army guys were going up a mountain to set up an observation post. They got ambushed.”

Aaron scooted up so I could hear him better:

“Monti was the staff sergeant, and he pretty much did a suicide run to get to a wounded private who was stuck in the kill zone. Monti kept getting pushed back, but then he would make another go. On his third try he got hit and didn’t make it. But he called in the helicopters before he made his run. Four guys were killed. Monti got the Medal of Honor. That’s why they named the place after him.”

For the record, Jared Monti, Brian Bradbury, Patrick Lybert, and Heathe Craig were the brave guys who didn’t come back from that one.

A half-hour earlier that afternoon we had rolled out of Camp Joyce, a forward operating base about ten miles south of our destination, Combat Outpost Monti.

In eastern Afghanistan in 2009, the U.S. Army provided the conventional battalions and the Marines supplied the advisors to the Afghan Army. Joyce was the headquarters for U.S. Army Battalion 1-32, tasked with preventing