(At one point, the crew of the

Frank Andrews was not the only person to come to this conclusion. In April 1963, soon after the accident, the secretary of the Navy formed a committee called the Deep Submergence Systems Review Group. The group’s mission was to examine the Navy’s capabilities for deep-ocean search and rescue and recommend changes. The group, chaired by Rear Admiral Edward C. Stephan, the oceanographer of the Navy, became known as the Stephan Committee.

The Stephan Committee released its report in 1964, advising the Navy to focus research in several key areas. The Navy should be able to locate and recover both large objects, such as a nuclear submarine, and small objects, such as a missile nose cone. It should train divers to assist in salvage and recovery operations anywhere on the continental shelf. Finally and most urgently, concluded the Stephan Committee, the Navy must develop a Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle (DSRV) to rescue submariners trapped in sunken ships. To make the Stephan Committee’s recommendations a reality, the Navy created a group called the Deep Submergence Systems Project, or DSSP.

The Deep Submergence Systems Project landed on the desk of John Craven, chief scientist of the Navy’s Special Projects Office, which had overseen the development of the Polaris nuclear submarine. Craven knew that the DSSP was supposed to advance ocean search and recovery operations, not military intelligence or combat. But according to Craven, the intelligence community soon saw a role for the DSSP far beyond what the Stephan Committee had envisioned. Instead of just search, rescue, and recovery, the new technology created for DSSP could be used to gather information on the Soviets, investigating their lost submarines and missiles. Craven considered this a fine idea, though it ran counter to the original spirit of the mission.

To staff the DSSP, Craven inherited a jumble of existing projects, such as SEALAB, a Navy program to build an underwater habitat where divers could live and work for months. Craven also inherited the

Senator William Proxmire awarded the project a “Golden Fleece” award for its monumental cost overruns, most of which, according to Craven, were simply being diverted to secret projects.

Nearly three years after the

In his keynote address, Under Secretary of the Navy Robert H. B. Baldwin said that this program, while chiefly serving the needs of the Navy, would also advance civilian science, engineering, and shipbuilding, and the general understanding of the ocean. Furthermore, he emphasized, DSSP was not just another money-sinking bureaucracy. Rather, it stood ready for action: I want to stress that we have no intention of building a paper organization with empty boxes and unfilled billets. Over 2,000 years ago, Petronius Arbiter stated:

“I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing; and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency and demoralization.”

The Deep Submergence Systems Program is a viable organization. It is here

Less than a week after Baldwin’s speech, two planes crashed over Spain and four bombs fell toward Palomares. In contrast to Baldwin’s rousing speech, the DSSP was not exactly ready to leap in with both feet. The DSSP had moved forward in some areas but had postponed or neglected others. The program called Object Location and Small Object Recovery, which could have come in quite handy in Spain, was scheduled for “accomplishment” in 1968 and later estimated for completion in 1970.

The Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle, which could have swum down to search for the bomb, had not yet been built. The DSSP did have the

The DSSP, created in 1964 for something exactly like the Palomares accident, simply was not ready.

We had “almost nothing,” said Craven. “No assignments had gone on, nothing,” said Brad Mooney, a thirty- five-year-old Navy lieutenant who had piloted the

9. The Fisherman’s Clue

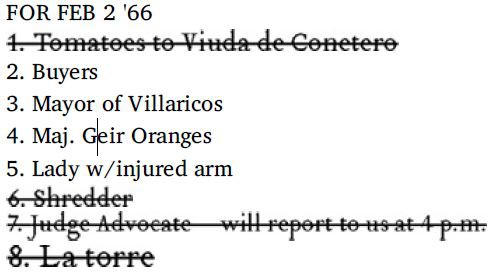

Back on dry land, the Air Force continued its tedious search for bomb number four. Joe Ramirez spent his days talking to locals, collecting data for damage claims, and listening for clues about the bomb. Conflicting information, possible leads, and various complaints whizzed around the young lawyer with dizzying speed. To keep track, he started jotting notes in a narrow notebook.

Other pages held more interesting notes. One page read, “Antonio Alarcon Alarcon — House is next one over to south of La Torre. Have been moved out. Pig with litter of pigs — litter has to be fed.

Why can’t they move the pigs?” Another page listed two names already well known to many searchers: Roldan Martinez and Simo Orts.

One person who hadn’t yet heard of the two fishermen was Randy Maydew, the Sandia engineer who had overseen the computer calculations suggesting that bomb number four might have landed in the sea. At the request of General Wilson, Maydew had flown to Spain to help narrow down the search area. He was surprised by how much the Almeria desert resembled Albuquerque, “except for that blue, blue Mediterranean out there.” But when he walked into Camp Wilson, he found that Air Force staffers didn’t have much regard for eggheads like him. This changed when General Wilson discovered that Maydew had also served in the Pacific during World War II. As a navigator in a B-29 bomber, Maydew had flown thirty bombing missions, including LeMay’s famous firebombing of Tokyo. The missions did more to establish Maydew’s credibility with General Wilson than his engineering degrees or his years of research on bombs and parachutes.

Though Maydew had won over General Wilson, by early February he was little closer to pinpointing bomb number four. Then, one morning, Joe Ramirez stopped by Maydew’s tent and told him about his interview with the Spanish fishermen. Ramirez knew that Roldan and Simo had seen something significant. Perhaps Maydew, with his engineering expertise, could put the pieces together. The engineer agreed to talk to Simo.

On the evening of February 2, Maydew and Ramirez drove to Aguilas and interviewed Simo in the mayor’s office. Simo told the men his story. He told them about the small parachute carrying a half man with his insides trailing. And he told them about the dead man, floating from a bigger chute, who had sunk before he could reach him. Maydew asked the fisherman how much the objects hanging from the chutes had swung in the sky. Moving his hand in the air, Simo indicated that the “half man” below the small chute hadn’t swung much, maybe about 10 degrees. But the “dead man” under the larger chute had oscillated about 30 degrees.

The information made sense: Maydew knew that the big sixty-four-foot chute would oscillate about 30 degrees as it fell, while the sixteen-foot chute would hardly sway at all. The engineer picked up a sheet of paper and roughly sketched the two parachutes, then asked Simo if they looked right. Simo examined the drawings and shook his head. Then he grabbed the pen and sketched his own, with greater detail. The engineer was astonished.