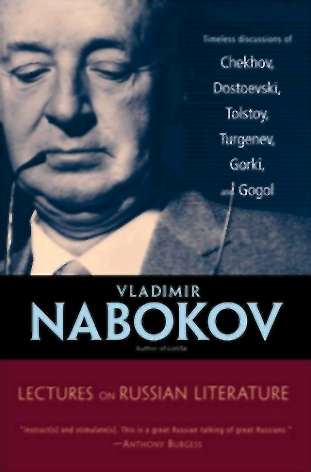

Vladimir Nabokov

LECTURES ON RUSSIAN LITERATURE

EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, by Fredson Bowers

It is difficult to refrain from the relief of irony, from the luxury of contempt, when surveying the mess that meek hands, obedient tentacles guided by the bloated octopus of the state, have managed to make out of that fiery, fanciful free thing—literature. Even more: I have learned to treasure my disgust, because I know that by feeling so strongly about it I am saving what I can of the spirit of Russian literature. Next to the right to create, the right to criticize is the richest gift that liberty of thought and speech can offer. Living as you do in freedom, in that spiritual open where you were born and bred, you may be apt to regard stories of prison life coming from remote lands as exaggerated accounts spread by panting fugitives. That a country exists where for almost a quarter of a century literature has been limited to illustrating the advertisements of a firm of slave-traders is hardly credible to people for whom writing and reading books is synonymous with having and voicing individual opinions. But if you do not believe in the existence of such conditions, you may at least imagine them, and once you have imagined them you will realize with new purity and pride the value of real books written by free men for free men to read.*

© 1981

ISBN 0151495998

*

This is a single untitled leaf, numbered 18, that appears to represent all that survives of an introductory survey of Soviet literature that VN prefixed to his lectures on the great Russian writers. Ed.

2

Contents

Introduction by Fredson Bowers 5

LECTURES ON RUSSIAN LITERATURE 11

Russian Writers, Censors, and Readers 12

NIKOLAY GOGOL (1809-1852) 19

Dead Souls (1842) 20 — 'The Overcoat' (1842) 41

IVAN TURGENEV (1818-1883) 45

Fathers and Sons (1862) 49

FYODOR DOSTOEVSKI (1821-1881) 67

Crime and Punishment (1866) 74 — 'Memoirs from a Mousebole' (1864) 77 — The Idiot (1868) 84 —

The Possessed (1872) 85 — The Brothers Karamazov (1880) 87

LEO TOLSTOY (1828-1910) 91

Anna Karenin (1877) 92 — The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1884-1886) 148

ANTON CHEKHOV (1860-1904) 153

'The Lady with the Little Dog' (1899) 159 — 'In the Gully' (1900) 164 — Notes on The Seagull (1896) 175

MAXIM GORKI (1868-1936) 183

'On the Rafts' (1895) 188

Philistines and Philistinism 191

The Art Of Translation 195

L'Envoi 199

APPENDIX: Nabokov's notes for an exam on Russian literature 201

The editor and publisher are indebted to Simon Karlinsky, Professor of Slavic Languages at the University of California, Berkeley, for his careful checking of the lectures and his advice on transliterations. Professor Kar-linsky's assistance has been crucial to this volume.

3

4

Introduction by Fredson Bowers

According to his own account, in 1940 before launching on his academic career in America, Vladimir Nabokov 'fortunately took the trouble of writing one hundred lectures—about 2,000 pages—on Russian literature. . . . This kept me happy at Wellesley and Cornell for twenty academic years.'* It would seem that these lectures (each carefully timed to the usual fifty-minute American academic limit) were written between his arrival in the United States in May 1940 and his first teaching experience, a course in Russian literature in the 1941 Stanford University Summer School. In the autumn semester of 1941, Nabokov started a regular appointment at Wellesley College where he was the Russian Department in his own person and initially taught courses in language and grammar, but he soon branched out with Russian 201, a survey of Russian literature in translation. In 1948 he transferred to Cornell University as Associate Professor of Slavic Literature where he taught Literature 311-312, Masters of European Fiction, and Literature 325-326, Russian Literature in Translation.

The Russian writers represented in the present volume seem to have formed part of an occasionally shifting schedule in the Masters of European Fiction and Russian Literature in Translation courses. In the Masters course Nabokov usually taught Jane Austen, Gogol, Flaubert, Dickens, and—irregularly — Turgenev; in the second semester he assigned Tolstoy, Stevenson, Kafka, Proust, and Joyce.† The Dostoevski, Chekhov, and Gorki sections in this volume are from Russian Literature in Translation, which, according to Nabokov's son Dmitri, also included minor Russian writers for whom the lecture notes are not preserved.‡

After the success of

Some differences mark Nabokov's presentation of the material from that he adopted for the European authors treated in the first volume,