every indentation has been set aside, and except for opening and closing marks and the usual marks about dialogue, the distinction between quotation and text has been deliberately blurred. When a useful purpose might be served, the editor has occasionally added quotations to illustrate Nabokov's discussion or description, especially when his teaching copies of the books are not available and one does not have the guidance of passages marked for quotation in addition to those specified in the body of the lecture as to be read.

Only the teaching copies for

(This teaching copy differs from that of

Nabokov was acutely conscious of the need to shape the separate lectures to the allotted classroom hour, and it is not unusual to find noted in the margin the time at which that particular point should have been reached. Within the lecture text a number of passages and even separate sentences or phrases are enclosed in square brackets. Some of these brackets seem to indicate matter that could be omitted if time were pressing. Others may represent matter that he queried for omission more for reasons of content or expression than for time restrictions; and indeed some of these bracketed queries were subsequently deleted, just as some, alternatively, have been removed from the status of queries by the substitution for them of parentheses. All such undeleted bracketed material has been faithfully reproduced but without sign of the bracketing, which would have been intrusive for the reader. Deletions are observed, of course, except for a handful of cases when it has seemed to the editor possible that the matter was excised for considerations of time or, sometimes, of position, in which latter case the deleted matter has been transferred to a more appropriate context. On the other hand, some of Nabokov's comments directed exclusively to his students and often on pedagogical subjects have been omitted as inconsistent with the aims of a reading edition, although one that otherwise retains much of the flavor of Nabokov's lecture delivery. Among such omissions one may mention remarks like 'you all remember who

structure : 'I realize that synchronization is a big word, a five syllable word—but we can console ourselves by the thought that it would have had six syllables several centuries ago. By the way it does not come from sin—s, i, n—but s, y, n—and it means arranging events in such a way as to indicate coexistence.' However, some of these classroom asides have been retained when not inappropriate for a more sophisticated reading audience, as well as most of Nabokov's imperatives.

Stylistically the most part of these texts by no means represents what would have been Nabokov's language and syntax if he had himself worked them up in book form, for a marked difference exists between the general style of these classroom lectures and the polished workmanship of several of his public lectures. Since publication without reworking had not been contemplated when Nabokov wrote out these lectures and their notes for delivery, it would be pedantic in the extreme to try to transcribe the texts

Corrections and modifications have been performed silently. Thus the only footnotes are Nabokov's own or else occasional editorial comments on points of interest such as the application of some isolated jotting, whether among the manuscripts or in the annotated copy of the teaching book, to the text of the lecture at hand. The mechanics of the lectures, such as Nabokov's notes to himself, often in Russian, have been omitted, as have been his markings for correct delivery of the vowel quantities in pronunciation and the accenting of syllables in certain names and unusual words. Nor do footnotes interrupt what one hopes is the flow of the discourse to indicate to the reader that an unassigned section has been editorially inserted at a particular point.

The transliteration of Russian names to their English equivalents has posed a slight problem since Nabokov was not always consistent in his own usage; and even when he made up a list of the forms of names in

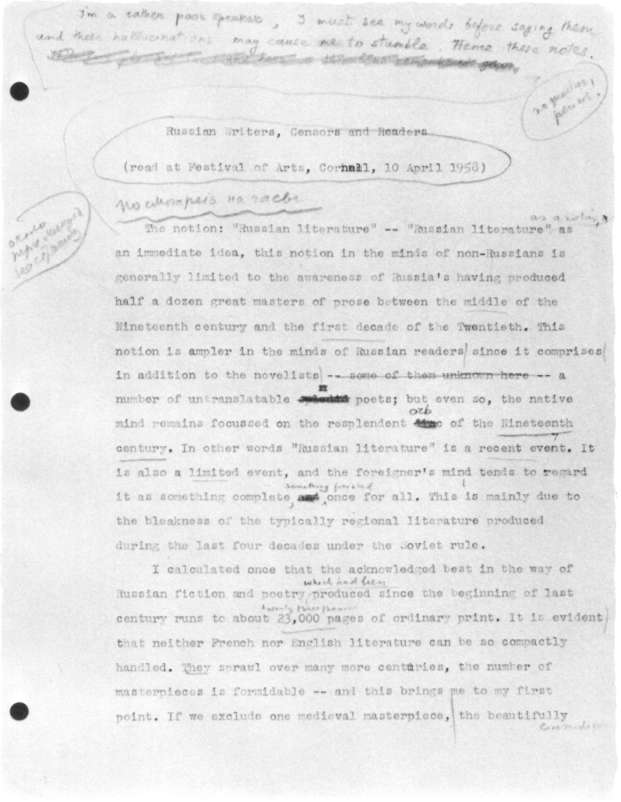

'L'Envoi' is drawn from Nabokov's final remarks to his class before he went on to discuss in detail the nature and requirements of the final examination. In these remarks he states that he has described at the beginning of the course the period of Russian literature between 1917 and 1957. This opening lecture has not been preserved among the manuscripts except perhaps for one leaf, which appears as the epigraph to this volume.

The editions of the books that Nabokov used as teaching copies for his lectures were selected for their cheapness and general availability. Nabokov admired the translations from the Russian of Bernard Guilbert Guerney, but of few others.

The texts from which Nabokov taught are as follows: Tolstoy,

10

Lectures on Russian literature