Scott Oden

Men of Bronze

'There was another thing which helped to bring about the Egyptian expedition. One of the Greek mercenaries of Pharaoh, being dissatisfied for some reason or other, escaped from Egypt by sea with the object of getting an interview with Cambyses. As this mercenary was a person of consequence in the army and had very precise knowledge of the internal condition of Egypt, Pharaoh was anxious to stop him …'

PART ONE

Year Forty-four of the reign of Kbnemibre Abmose

(526 BCE)

1

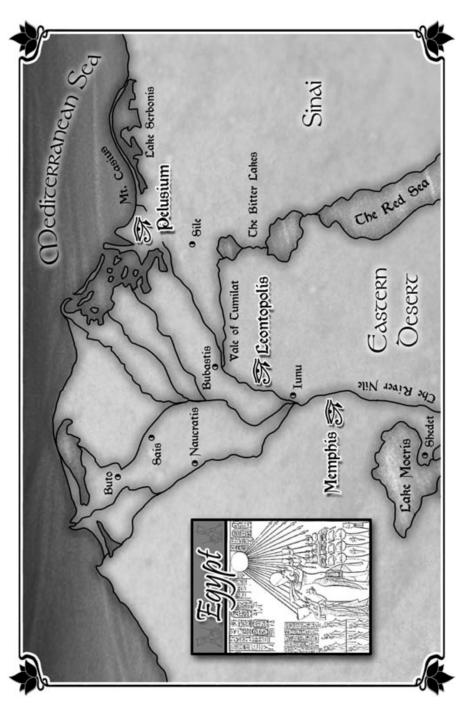

In the blue predawn twilight, a mist rose from the Nile's surface, flowing up the reed-choked banks and into the ruined streets of Leontopolis. Remnants of monumental architecture floated like islands of stone on a calm morning sea. Streamers of moisture swirled around statues of long-dead pharaohs, flowed past stumps of columns broken off like rotted teeth, and coursed down sandstone steps worn paper-thin by the passage of years. As the sky above grew translucent, streaked with amber and gold, a funerary shroud settled over the City of Lions, a mantle that disguised the approach of armed men.

From the desert came two score and ten dark shapes clad Greek-fashion in leather cuirasses and studded kilts, Corinthian helmets perched atop their foreheads. Bowlshaped shields hung from their shoulders by gripcords of plaited hemp, freeing each man to wield a short, recurved bow. They moved in earnest, silent, a company of phantoms drifting through the fog.

The Medjay had come to Leontopolis.

Medjay. The soldiers bearing this appellation were the most savage of Pharaoh's mercenaries. They were a cadre of outcasts, criminals in their own lands, who banded together under Egypt's banner to dedicate their lives to the gods of violence. The emblem painted on their shield faces, the uadjet, the all-seeing Eye of Horns, symbolized their task as guardians of the eastern frontier. Pharaoh paid them to be vigilant, to crush any intruders before they could reach even an abandoned ruin such as Leontopolis, and he paid them well. This time, though, the Medjay had failed their royal paymaster.

To a man, they froze as the rasp of metal on stone drifted through the mist; instinctively, their eyes sought out the massive silhouette of their commander. Phoenician by birth, Hasdrabal Barca ruled the Medjay with the tigerish strength of a born killer. Spear, arrow, torch, and sword, all this and more had touched his flesh, leaving behind the indelible scars of a lifetime spent waging war. He disdained a helmet; long black hair, shot through with gray, fell over his face as he stood with head bowed, straining to hear.

The clatter came again, followed by sibilant cursing.

Barca looked up; his eyes turned to slits, like splinters hacked from the iron gates of Tartarus. He motioned, and a young soldier, a Libyan, edged up to his side. The Phoenician dragged his index finger across his throat in a chilling pantomime. Nodding, the soldier handed his bow and shield off to another, removed his helmet, and drew a curved knife from the small of his back. Beneath a thatch of sandy hair, plastered with sweat, the young Medjay's eyes shimmered with anticipation as he crept off to do Barca's bidding.

Raids like this were nothing new. The desert-folk of Sinai, the Bedouin, encroached on Egypt's borders every season, fleeing tribal feuds or seeking succor from generations of drought. The Medjay turned most back at the Walls of the Ruler, a line of ancient fortifications stretching from Pelusium on the coast, along the Bitter Lakes, to the Gulf of Suez. A few, though, slipped through the Medjay's nets to plunder the border villages. Such was the fate of Habu, south of the vale of Tumilat, on the shores of the Great Bitter Lake.

Habu lay on the patrol route between Sile and Dedun, on the Gulf; it was a small village of two dozen mud brick huts clustered around a brackish well whose inhabitants mined salt in the nearby hills. The Medjay, following the Bedouin's trail, found Habu in ruins. Barca recalled the mound of severed heads in the village square, the corpses left to rot in the merciless sun. The men were killed outright, the women raped and mutilated. Even the children …

Barca's scout returned as quietly as he had left. He made a show of wiping his knife on a Bedouin headscarf.

'You were right,' the scout, Tjemu, whispered, 'they are the Beni Harith.'

'How many?' Barca's voice did not carry past the Medjay's ear.

Tjemu nodded back the way he had come. 'Maybe twice our number, camped in a square some hundred yards beyond a causeway of crouching stone lions. Their pickets are asleep. Careless bastards.'

'They're not expecting us.' Barca's jaw tightened; deep in his soul he felt the Beast stir, flexing its claws. Even the children. 'Fan out! ' he ordered, raising his fist.

Sinew creaked as the Medjay bent their bows.

The Bedouin camp stirred and came alive. The younger men fetched water from the Nile's bank while their elders sat in council before the camelhair tent of their shaykh, Ghazi ibn Ghazi. Four of his brothers, an uncle, and seven nephews reclined on their blankets, talking in low voices about this last stage of their journey. Spear butts and sheathed swords clattered on the cracked paving stones; tethered camels bawled, as unhappy about the claustrophobic mist as their masters were.

Ghazi ibn Ghazi plucked a date from a wooden bowl and popped it into his mouth. Age, sand, and sun had left his face fleshless, seamed, an uncured hide stretched tight over a frame of bone. His eyebrows and beard were gray and sparse, his shoulders stooped, calling to mind a wizened shoemaker rather than a Bedouin war leader.

'This place is accursed! ' the man on his right said, with all the frustrated weariness of one who had not slept soundly in days. He wore clothing similar to his Bedouin companions — robes of grimy brown wool and a once-white head scarf held in place by a leather band — but his accent and manners marked him as a Persian. 'It is fit for jackals, perhaps, or Bedouin, but it is no place for a man of refinement.'

Ghazi grinned. 'Where are your balls, Arsamenes? Have you Persians become so civilized that you can no longer stomach the hard road?'

The Persian, Arsamenes, leaned forward, helping himself to the dates. His eyes, small and dark, flickered up to the Bedouin's face. 'We could have been done with the hard road, and in Memphis already, had you not stopped to glut yourself on that flyspeck of a village.'

At this, the other Bedouin ceased their own conversations. This was not the first time the Persian had broached that topic.

'I told you before,' Ghazi said quietly, 'Habu is none of your concern.'

'Will the Medjay not notice the slaughtered villagers? Will they ignore the spoor of a hundred camels leading in country from Sinai? You fool! Everything about this mission is my concern! You have jeopardized it, and I want to