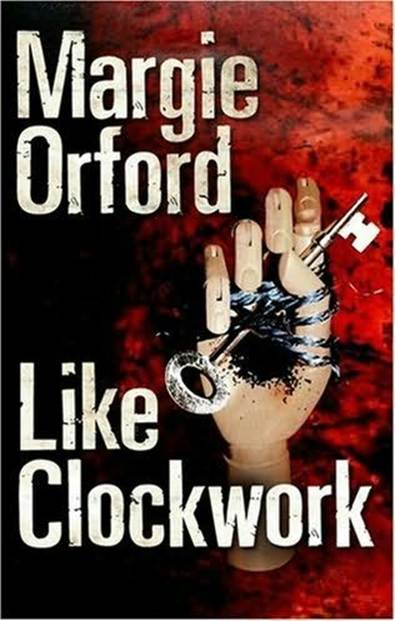

Margie Orford

Like Clockwork

A book in the Clare Hart series, 2006

For Andrew

PROLOGUE

The man watches the cigarette burning between the fingers of his right hand. The cuff of his silk shirt strains against his lean wrist, the cuff link glinting in the artificial light. Although the room is hidden at the centre of the house – a warren of rooms and passages – he hears the thud-thud of slammed car doors in the garage. He raises his head, close-cropped and scarred in places, and listens. He waits. He knows how long it will take. Then he uncoils himself from the leather chair. He walks to the door that slides open at a touch. This room and its records are not visible from anywhere. No one ever enters it.

Two strides take him to the room where they have brought the new consignment. She looks at him, terrified. He finds this provocative. He holds out his hand to the girl. Conditioned to politeness, confused, she gives him hers. He looks at it. Then he turns the palm – secret, pink – upwards. He looks into her eyes and smiles. He stubs the cigarette out in her hand.

‘Welcome,’ he says.

The girl watches her heart line, curving round the plump mound of her thumb, burn away. Her sharp, shocked intake of breath breaks the silence.

‘What’s your name?’ he murmurs, smoothing her long hair behind her ear.

‘I want to go home,’ she whispers. ‘Please.’

The man strokes the rounded chin, her soft throat. Then he turns and walks back to his office. He is used to power, there is no need to swagger. He knows that the girl will not take her eyes off him. He punches a number into his phone. The call is picked up at once.

‘I have a little something for you. Fresh delivery. No, no other takers as yet.’ He laughs, turning to watch as the girl is led out, before ending the call.

Many hours later, the girl sits huddled in the corner of a room, unaware of the unblinking eye of the camera watching her. She is alone, knees pulled tight into her body. A blanket, rough and filthy, is wrapped around her. Her clothes are gone. She shivers, cradling her hand in her lap, the fingers trying to find a way to lie that will not hurt the burnt pulp at the heart of her palm. Her skin is tattooed with the sensation of clawing hands, bruised from her brief resistance. She hugs her knees. The effort makes her whimper. She cringes at the sound, dropping her head, unable to think of a way of surviving this. And she is too filled with hatred to find a way to die. After a long time, she lifts her head.

Something that the camera does not see: to survive, she thinks of ways of killing.

The door opens. ‘Dinner, sir,’ announces the maid, transfixed by the image on the screen.

A finger on the remote and the bruised girl vanishes.

‘Thank you,’ says the host. He turns to his guests. ‘This way, gentlemen.’

The maid gathers glasses and ashtrays after they have left the room. She switches off the lights and closes the door and goes downstairs to help serve the meal.

1

It was old Harry Rabinowitz, out for an early morning walk, who found the first body. Her throat had been precisely, meticulously sliced through. But that was not the first thing he noticed. She lay spreadeagled on the promenade in full view of anyone who cared to look. Her face was child-like in death, dark hair rippling in the breeze. Blood, pooled and dried in the corners of her eyes, streaked her right cheek like tears. Her exposed breasts gestured towards womanhood. One slender arm was lifted straight above her head; the fingers of the left hand were extended, like a supplicant’s. The right hand – its fingers clenched – had been bound with blue rope, and rested on her hip.

A bouquet, just like a bride’s, had been placed next to her. Later on, in the ensuing jostle of people approaching, then recoiling, the flowers were trampled, becoming part of the gutter debris.

He had stopped in shock next to the dead girl. The pounding of his heart deafened him. Darkness gathered in the periphery of his vision. He turned away from her and leant on the solid mass of the sea wall, gulping in the cold morning fog. He watched as a group of old women approached. He lifted his arm in a feeble effort to summon help. The women waved back. It was only when they were close to him that he could get them to stop waving and look at the dead girl. They flocked around the body.

Ruby Cohen had recognised Harry and scurried over to take his arm. ‘You look terrible, Harry. Come and sit down.’ She led him to an orange bench. He sat down, waiting for his heart to quieten, grateful to her. Ruby made sure that he was settled before returning to her friends.

‘You call the ambulance,’ Ruby ordered. ‘I’m going to ask Dr Hart for help. There’s her flat, next to the lighthouse.’ Harry watched her stride off officiously.

More people arrived. Some, he noticed, gagged at the sight of the dead girl. Harry pulled his coat closed. When I’m not so cold, when I regain my strength, he thought to himself, I’ll cover her.

2

Last night’s chill seeped from the floor into Clare’s bare feet despite the sunlight filtering through the window. But she was too lazy to go and fetch her slippers. The muted rush and retreat of the waves against the sea wall was comforting after the chaos of the storm that had spent itself an hour before dawn. As Fritz wound herself around Clare’s legs, she tipped a heap of crumbles into the purring cat’s bowl. The morning routine anchored her. She waited, watching the steam snaking up, her hand braced on the coffee plunger. The grounds formed a satisfying resistance to her hand as she pressed down firmly.

Clare poured the coffee and sat down at the table. Fritz leapt into her lap and purred, kneading her thighs rhythmically. The pain was pleasant. Clare stroked her and straightened the newspaper. She read the surfing report. She drank more coffee and read the weather forecast. It would be fine weather for the next few days.

It wasn’t working, but Clare had learnt not to panic if she failed to keep herself in the present. She tried a different tack.

Shopping. She would go shopping. There was nothing to eat in her flat and she needed new towels. Clare picked up a pencil and started to make a list.

Sugar.

More coffee.

Loo paper.