The 15-inch Wanstone battery was not ready and the six old-fashioned heavy guns were far too slow against moving targets — except for a thousand-to-one lucky shot.[5]

If the ships hugged the French coast, the fast-firing six-inch British guns could not reach them.

The only dangerous guns were the 9.2s at South Foreland. As with everything else in this operation, this peril depended on whether the British had sufficient warning. With good advance information, their 9.2 guns in the narrow Straits might be able to lay down an arc of fire to damage or disable the ships enough for them to be finished off by the Navy or the RAF.

As they approached the Straits the German Captains had one great fear — was there any possibility that their reconnaissance might be proved wrong? Did the British have extra heavy long-range batteries hidden, which could turn the Dover passage into a cauldron of fire?

V

A GROUP CAPTAIN OBEYS ORDERS

Just after eight o'clock it was raining in the English Channel, but the wind was moderate and the sea fairly calm. The German warships, at sea for more than ten hours, had covered 250 miles and were only fifteen minutes behind their planned timetable. Speeding at nearly thirty knots, which they had maintained most of the night, the battleships were almost exactly where they should be, in spite of the failure of their radar aids to navigation.

No one had detected them yet. So far the bluff had succeeded. The Admiralty in London remained blissfully convinced that the battleships were still in Brest.

Just after dawn, the German ships were off Barfleur and had almost caught up on their timetable. It was colder up-Channel than it had been at Brest but there was some February sunshine. The morning wore on with little incident. The official cameraman filmed shipboard scenes in the intervals of bright sunlight. The gun crews had a meal of lentil soup and sausage and coffee.

They knew it would be their last hot meal for a long time. One problem to which the planning staff had paid great attention was victualling for the lengthy period at battle-stations. As the two cooks detailed for service during action could not prepare warm meals, concentrated rations were deposited at each combat station, to be opened only on orders. For the German planners knew that combat excitement, with its physical over-exertion, can be best removed by small repeated amounts of food. The ships' doctors went round distributing slabs of chocolate and vitamin tablets.

Everyone remained tense. For the crews of all the big ships now understood why Luftwaffe staff officers and additional A.A. crews had embarked before sailing. The decks and even the coverings of the gun turrets bristled with flak guns.

The state of tension was revealed when

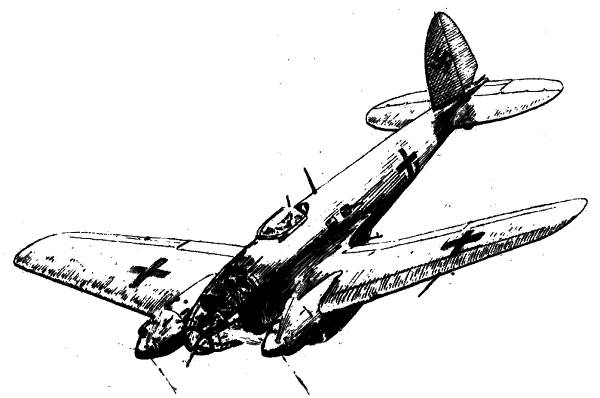

When the task force was off the mouth of the Somme— about forty miles from Dover — the night-fighters were replaced. They flew to Holland for refuelling, ready to guard the ships again in the evening. The fighter escort was taken over by Messerschmitt 109s.

The fact that the German ships were still steaming undetected in full daylight up the Channel was due to the failure of the RAF Coastal Command night patrols. This combination of bad luck and inefficiency was beginning to emerge as the pattern for the operation from the British side.

Now it was the turn of the day patrols. At dawn and dusk every day one Spitfire patrolled from Cap Gris Nez to Flushing, another from Cap Gris Nez to Le Havre. If they sighted anything important their orders were to maintain radio silence, return to base and report. The German battleships were nearing Dieppe when the Spitfires known as the 'Jim Crow' patrol took off

Commanding 'Jim Crow,' from 91 Squadron stationed at Hawkinge near Manston, was Sq. Ldr. Bobby Oxspring. His squadron's task was to cover the coastal ports and try to discover any overnight movements of ships. It was called the 'Milk Run.'

There was no liaison between Oxspring's squadron and the Coastal Command 'Habo' patrol, which came off patrol as dawn broke, to be relieved within minutes by 'Jim Crow' Spitfires. Neither was aware of each other's existence. But this lack of liaison had an even more serious aspect. Oxspring and his pilots had no knowledge of the code-word 'Fuller.' The RAF had become so security-minded that no one had told the 'Jim Crow' squadron that this was the warning code-message for the possible emergency of a German battleship dash through the Channel. It had been unofficially passed, often on the 'old boy net,' to RAF controllers like Bill Igoe at Biggin Hill, Southern England's most important fighter base, but it appeared to be unknown to the duty officers at No. 11 Group at Uxbridge, which controlled the hundreds of fighter aircraft over southern England.

When the two 'Jim Crow' Spitfires went out as usual that morning, the Cap Gris Nez-Le Havre Spitfire spotted some fast-moving light craft leaving Boulogne. These were the German E-boats congregating to escort the battleships through the Straits of Dover. As he flew on towards Dieppe, clouds came right down on to the sea and as he could see nothing he returned to base. He did not know that the German battleships were steaming just behind the weather screen. Fifteen minutes later they appeared exactly where he had been patrolling.

The second Spitfire on the Flushing run only sighted seventeen small vessels off Zeebrugge, which looked like fishing smacks. Obeying orders to maintain radio silence during flight, both planes returned to base to report what they had seen.

This blanket radio silence appears inexplicable after the event. Yet there was a good reason for it. At that time big RAF fighter sweeps were being carried out daily over France. Hundreds of aircraft piloted by brave but young crews took part. If someone started talking over the radio, the German direction finders would soon pinpoint them at whatever height they were flying — whether at ground level or 15,000 feet — and attack. To avoid this, orders were given that everyone must be silent unless an emergency occurred.

It was upon the interpretation of what was an 'emergency' that much depended. Later that morning two RAF officers flying in Spitfires over the Channel were to put entirely different meanings on it.

When the two 'Jim Crow' Spitfires landed, British coastal radar stations were already registering numerous 'blips' which seemed to come from German aircraft constantly changing course.

But how many early radar warnings were ignored? David Jackson, a 23-year-old lance-bombardier, was in charge of a radar detachment in a wooden cabin perched on the tip of Beachy Head. For weeks their old M-set with bedstead aerials suffered from continual interference, which they called 'running rabbits and railings.' They were certain this persistent jamming was caused by the Germans. They switched off their old-fashioned M-sets and used the K-set, which they had had for only three months. It was a newer, more efficient short-wave radar, which the Germans did not know existed and therefore could not jam.

Just before dawn Jackson's detachment plotted something moving too fast for shipping, and assumed it to be a heavy movement of German aircraft over the Channel. After fifteen minutes the plot faded. Although being gunners their job was to look for ships only, they decided to advise the RAF about this unusual plot. They also reported it to Naval H.Q. at Newhaven. But as their report did not concern shipping, the Wren who answered the phone was not very interested. Neither was the RAF This sort of situation occurred on many airfields and radar stations during the morning.

Aboard the German ships everything was peaceful. The weather was still fine and there was no sign of the British. The only problem was exact navigation. One of the officers said jokingly to Giessler, 'This could well be an instruction trip for quartermasters.' It was so quiet that the crews began to worry. Why were the British apparently doing nothing? Was it all a dreadful trap?

They did not know that all morning General Martini's electronic interference had almost completely deceived