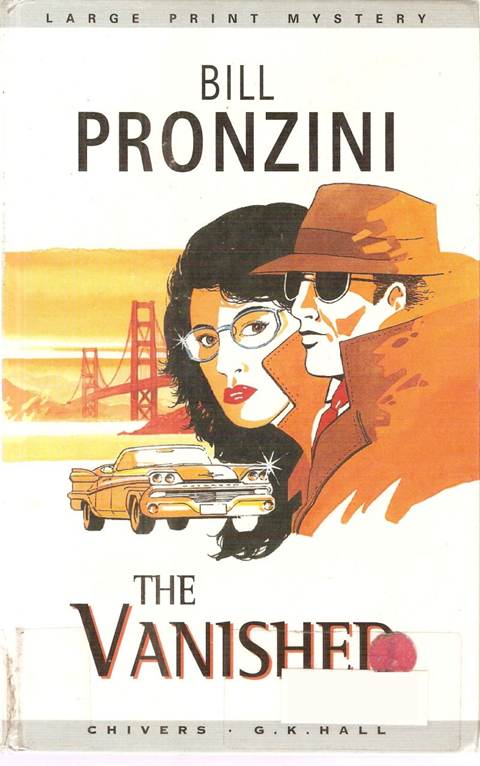

Bill Pronzini

The Vanished

The second book in the Nameless Detective series, 1973

Chapter One

January.

A new year, another year-but nothing really changes. The passage of Time is inexorable, but Man is a constant, Man does not change, Man loves and hates and lives and dies exactly as he did millenniums ago. The same emotions govern his actions, the same things, in essence, delight or repulse or frighten or sadden him. The chosen are still the chosen, the lonely still the lonely.

January.

The bitter-cold winter air still smells of pollution, and wars like the amusements of mad children are still being fought in alien jungles. Poverty and disease, affluence and medical science, exist side by side, and Man ignores them all in the pursuit of shelter, career, nourishment, orgasm. Nothing has changed, and nothing will, because Man is Man-and a constant.

January.

A weekday morning four days after the one night in the year which should not be spent alone, a night I had spent alone, a night when I said ‘Happy New Year!’ to a roomful of silent emptiness and toasted Erika and toasted my convictions and toasted the fact that it was a new year and yet nothing had changed. A weekday morning like all the rest: cold, purposeless, giving birth to philosophical reflections which degenerate rapidly into little more than morbid self-pity.

And then the office door opens, and a ray of hope comes in, and suddenly it is not quite so dark outside or in, life is not quite so futile as it seemed seconds earlier. All you need, when you’re feeling this way, is a purpose, a place to channel your energies, a way to end the maudlinism, the melancholy. All you need is your work, the thing in your life that motivates you, that brings you alive, that allows you to forget the loneliness and the emptiness of a crumbled love. That’s all you need.

No. That’s

But at the moment, it is enough.

Her name was Elaine Kavanaugh, and she sat stiffly, nervously, in the leather-backed chair across my desk. She was a couple of years past thirty, with short dark hair and very white skin that held an almost brittle translucence, like opaque and finely blown glass. A pair of silver-rimmed glasses gave her oval face a studious, intense appearance. When the flaps of her tailored woolen coat fell open across her joined knees, I could see the hem of a medium-length blue skirt and nicely tapering legs in dark nylon.

She was small-breasted and narrow-shouldered, but attractive enough in a fiercely virginal sort of way-the kind of girl who would cry miserably on her wedding night. And yet, there was also a strangely muted sensuality about her, a hidden-below-the-surface kind of thing, so that while you had the thought of her weeping after the consummation of marriage, you felt she would probably become an active sexual aggressor in no time at all. There were small, expensive black pearls in the lobes of her ears, and on the third finger of her left hand was a diamond- encrusted engagement ring that would have cost upward of a thousand dollars if the diamonds were genuine.

I offered her a cup of coffee, but she shook her head; I got up and refilled my own cup from the pot on the two-burner I keep and sat down again. I watched her chew diffidently at the pale iridescent lipstick on her mouth. Her eyes, behind the lens of the glasses, were a magnified coltish brown, the pupils very black, the whites clean ivory; she had them focused on a spot several inches beyond my left shoulder, and her eyelashes flicked very rapidly up and down, like miniature black hummingbirds.

She said, ‘I don’t quite know how to begin.’

‘I understand,’ I told her. ‘Take your time.’

‘Thank you.’

She cleared her throat, softly, and looked down at the large white beaded purse she was holding in her lap. While I waited for her to make up her mind to begin, I reached a cigarette out of the pack by the phone and began to roll it back and forth across the blotter without looking at it. I had been trying to give the damned things up for better than two months now, because of a fluctuating cough and a rasping in my chest that may or may not have been something worthy of medical attention; but they were the kind of habit that for some men is not easy to break, a crutch, a friend in times of stress, a thing to do with your hands and mouth and lungs when you’re uptight or impatient or inactive. I had managed to cut down on my consumption from almost three packages daily to less than one, but that was the best I had been able to do; it was the best I would at any time be able to do. The cough came only in the mornings now, and I was breathing somewhat easier, more freely. I knew I should still see a doctor, but I could not seem to bring myself to do it. I had never liked doctors, not since the Second World War and the things I had seen in the field hospitals in the South Pacific.

I kept on rolling the cigarette under my index finger, resisting it, and finally Elaine Kavanaugh finished composing her thoughts and said, ‘I’ve come about my fiance, Roy Sands. He’s missing, you see.’

‘Missing?’

‘Yes, he’s disappeared.’

‘How do you mean, Miss Kavanaugh?’

‘Well, he’s just… vanished,’ she said, and made a vague, helpless gesture with her hands. ‘No one seems to know what happened to him.’ She lowered her eyes and tightened her fingers around the beaded bag. ‘We… we were to be married later this month, Roy and I, we were going to drive up to Reno and see a justice of the peace and spend our honeymoon up there…’

Oh Jesus, I thought, not one of these things, not now. I put the cigarette in my mouth and lit it and pulled deeply at it. As I dropped the match into the glass desk ashtray, my hand, through the exhaled smoke, seemed to look like one of those gnarled rubber affairs the kids wear on Halloween.

I said, ‘Miss Kavanaugh…’

‘I know what you’re thinking,’ she said before I could get the rest of it out. ‘The prospective bridegroom has serious second thoughts and departs for points unknown. That’s it, isn’t it?’

I did not say anything.

‘Well, you’re wrong,’ she said with conviction. ‘I’ve known Roy for a long time- over two years now-and his marriage proposal wasn’t one of those meaningless things made in a moment of… Well, we talked about it very carefully before we decided to marry, we were very sure of one another.’

‘I see.’

‘He wouldn’t just run off, not this way.’

‘And what way is that?’

‘Without telling me,’ she said. ‘Just… vanishing. His last letter from Germany, just a week before he came home, was very explicit about our plans. He wanted me to use part of our money for a down payment on this house I had written about in Fresno. That’s where I live, you see, in Fresno.’

‘Yes, that’s right. Roy and I have more than fifteen thousand dollars in our joint checking and savings accounts.’

I sat up a little straighter and put my cigarette out in the ashtray; the smoke from it was like a screen between us. When the screen faded into nothingness, I said, ‘How much of that amount is legally your fiance’s?’