Why did we get lucky with the first riddle? he says.

Because I had that dream.

No, he says, finding the page with Michelangelo's sculpture of Moses, the picture that began our partnership. We got lucky because the riddle was about something verbal, and we were looking for something physical. Francesco didn't care about actual, physical horns; he cared about a word, a mistranslation. We got lucky because that mistranslation eventually manifested itself physically. Michelangelo carved his Moses with horns, and you remembered that. If it hadn't been for the physical manifestation, we would never have found the linguistic answer. But that was the key: the

So you looked for a linguistic representation of the directions.

Exactly. North, south, east, and west aren't physical clues. They're

There are three sentences written on the page:

Winsomely? I say.

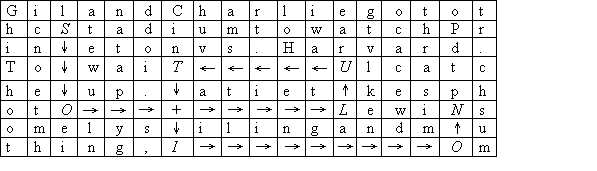

Doesn't look like much, right? It just sort of rambles, like Poliphilo's story. But plot it out in a grid, he says, turning the piece of paper over. And you get this:

I'm waiting for something to jump out at me, but it doesn't.

That's it? I ask.

That's it. Just follow the directions. Four south, ten east, two north, six west. De Studio-'from stadium.' Start with the V in 'stadium.'

I find a pen on his desk and try it out, moving down four, right ten, up two, and left six.

I write down the letters S-O-L-U-T.

Then repeat the process, he says, starting with the last letter.

I hegin again from T.

And there it is, laid out on the page: S-O-L-U-T-I-O-N.

That's

But it must've taken Colonna months to write.

He nods. The ninny thing is, I'd always noticed there were certain lines in the

Paul points to the line where O, L, and N appear.

See how many cipher letters are on that one line? And there'll be another one once you go six west again. The four-south, two-north pattern doubles back on itself, so every other line in the

But the letters in the book aren't printed that way, I say, wondering how he applied the technique to the actual text. Letters aren't spaced evenly in a grid. How do you figure out what's exactly north or south?

He nods. Yon can't, because it's hard to say which letter is directly above or below another. I had to work it out mathematically instead of graphically.

It still amazes me, the way he teases simplicity and complexity out of the same idea.

Take what I wrote, for example. In this case there are—he counts something-eighteen letters per line, right? If you work it out, that means 'four south' will always be four lines straight down, which is the same as seventy-two letters to the right of the original starting point. Using the same math, 'two north' will be the same as thirty-six letters to the left. Once you know the length of Francesco's standard line, you can just figure out the math and do everything that way. After a while, you get pretty quick at counting the letters.

In our partnership, it occurs to me, the only tiling I ever had that could compare to the speed of Paul's reasoning was my intuition-luck, dreams, chance associations. It hardly seems fair to him that we worked together as equals.

Paul folds the sheet of paper and places it in the trash can. For a second he looks around the carrel, then lifts a stack of books and places it in the crook of my arm, followed by a stack for himself. The painkiller must still be working, because my shoulder doesn't buckle under the heft.

I'm amazed you figured it out, I tell him. What did it say?

Help me put these away back on the shelves first, he answers. I want to empty this place out.

Why?

Just to be safe.

From what?

He half— smiles at me. Library fines?

We exit the carrel and Paul guides me toward a long corridor extending far into the darkness. There are bookshelves on either side, branching off into aisles of their own, dead ends begetting dead ends. We are in a corner of the library visited so rarely that the librarians keep the lights off, letting visitors flick the switch on each shelf when they come.

I couldn't believe it, when I finished, he says. Even before I was through decoding, I was shaking. It was done. After all this time, done.'

He stops at one of the rearmost shelves, and I can make out only the silhouette of his face.

And it was worth it, Tom. I never even saw it coming, what was in the second half of the book. Remember what we saw in Bill's letter?

Yes.

Most of that letter was a lie. You know that work is mine, Tom. The most Bill ever did was translate a few Arabic characters. He made some copies and checked out some books. Everything else I did on my own.

I know, I say.

Paul covers his mouth with his hand for a second.

That's not true. Without everything your father and Richard found, and everything the rest of you solved- you, especially-I couldn't have done it. I didn't do it all on my own. The rest of you showed me the way.

Paul invokes my father's name, and Richard Curry's, as if they are a pair of saints, two martyrs from the paintings in Taft's lecture. For a moment I feel like Sancho Panza, listening to Don Quixote. The giants he sees are nothing but windmills, I know, and yet he's the one who sees clearly in the dark, and I'm the one doubting my eyes. Maybe that's been the rub all along, I think: we are animals of imagination. Only a man who sees giants can ever stand upon their shoulders.

But Bill was right about one thing, Paul says. The results will cast a shadow over everything else in historical studies. For a long time.

He takes the stack of books from my hands, and suddenly I feel weightless. The corridor behind us extends toward a light in the distance, open aisles verging off into space on each side. Even in the darkness, I can see the