Scanned by Highroller.

Proofed by Highroller.

Made prettier by use of EBook Design Group Stylesheet.

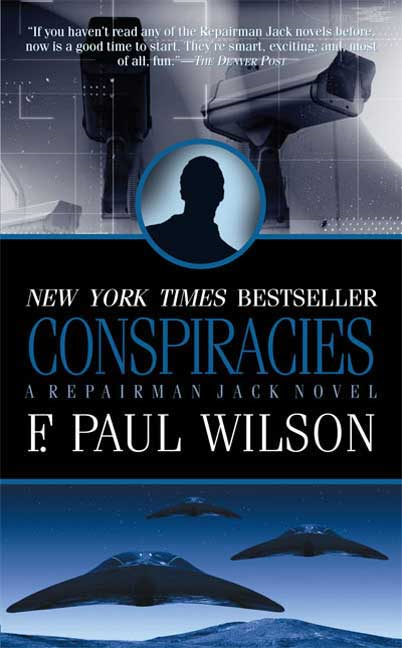

Conspiracies by F. Paul Wilson

for

Ethan Paul Bateman (E-Man!)

Special thanks to

Tom Valesky (again) and

Gerald Molnar for their marksmen's eyes for weapons errors.

TUESDAY

1

Jack looked around the front room of his apartment and figured he was either going to have to move to a bigger place, or stop buying stuff. He had nowhere to put his new Daddy Warbucks lamp.

Well, not new exactly. It had been made sometime in the 1940s, but it was in great shape. The base was a glazed plaster cast of Daddy from the waist up, his hand gripping a lapel of his tuxedo, a tiny rhinestone in place of his diamond stick pin. He was grinning, and his pupilless eyes showed not the slightest trace of concern about the lamp stem and socket shell emerging from his bald pate.

Jack had found it in a Soho nostalgia shop, and talked the owner down to eighty-five dollars for it. He would have paid twice that. The apartment didn't need another lamp, but Jack needed this one. Warbucks was such a stand-up guy. No way Jack could pass it up. No bulb or lampshade, but that was easily remedied. Problem was, where to put it?

He did a slow turn. His home was the third floor of a brownstone in the West Eighties, and smelled of old wood. Not surprising since the place was crammed with Victorian golden oak furniture. The walls and shelves were cluttered with memorabilia and tchotchkes from the thirties and forties. Everything in sight except for the computer monitor existed before he was born. Even the Cartoon Network—he could see the large-screen TV in the extra bedroom—was playing a toon from the thirties with a big-eyed owlet crooning how he loved 'to sing-a, about the moon-a anna June-a anna spring-a…' And here in the front room, not a single empty horizontal surface left…

Except for the computer monitor.

Jack placed the Daddy Warbucks lamp on top of the monitor, which sat atop Jack's antique oak rolltop desk. The processor sat on the floor in the kneehole, and the keyboard hid under the rolltop. The monitor didn't look comfortable perched up there, but then, the computer didn't really fit anywhere in the room—a plastic iceberg adrift in a sea of wavy-grained oak.

But you couldn't be in business these days without one. Jack didn't understand all that much about computers, but he loved the anonymity they afforded in communications.

He hadn't checked his email since this morning, so he lit up the monitor and rolled up the tambour top to reveal his keyboard. He logged on through one of his ISPs—Jack had multiple accounts under various names with a number of Internet service providers, and maintained a Web site through one of them. Everything he'd read said that people were increasingly looking to the Internet to solve all sorts of problems, so Jack figured he might as well make himself available to folks searching there for his kind of solution.

Half a dozen emails from the Web site waited, but only one seemed worth answering, and that barely:

It was signed 'Lewis Ehler' and he'd left two numbers, one in Brooklyn, the other on Long Island.

He had another job just starting up, but that promised to be mostly night work. Which meant his days would be free.

He wrote down the numbers, then headed out to make the call.

2

Jack walked east toward Central Park, looking for a phone he hadn't used recently, while the little toon owl's song echoed in his head.

Spring had sprung and NYC was lurching out of hibernation. The air smelled fresh and clean, bright flowers peeked from window boxes on the upper floors of the brownstone regiments, and tiny leaf buds bedizened the branches of the widely spaced trees set in the sidewalks. The late morning sun sat high and bright, keeping Jack comfortable in a work shirt and jeans. Winter coats were gone, leaving short skirts and long legs on display again. A good day to be alive and heterosexual.

Not that the women paid much attention to him. They barely seemed to notice the guy with the so-so build, average-length brown hair, and mild brown eyes. Which was just fine with Jack. He'd be disappointed if they did, considering the effort he put into being a walking

Jack cultivated anti-presence. The anonymous look took effort—not too trendy, not too retro. He kept an eye on what the average guy on the street was wearing. Jeans and flannel shirts never went out of style, even here on the Upper West Side; neither did sneakers and work boots—

He found a pay phone on Central Park West. The apartment buildings stopped dead here, as if sliced off with a knife for dozens of blocks in either direction to leave room for the park across the street. Through the still-naked trees he could see the Lake, a blue lozenge in the greening grass. No boats on it yet, but it wouldn't be long.

He tapped in the access number on his prepaid calling card. He loved these things. As anonymous as cash and a hell of a lot lighter than the pocketful of change he used to have to carry.

Everybody seemed so frightened of the potential threat new electronics posed to security. And maybe it was a genuine peril for citizens. But from Jack's perspective, electronics offered an anonymity bonanza. He used to keep an answering machine in an empty office on Tenth Avenue, but a few months ago he unplugged it and had all calls to that number forwarded to a voice-mail service.

Email, voice mail, calling cards…he could almost hear Louis Armstrong singing, 'What a wonderful world.'

Jack punched in the Brooklyn number Ehler had left. He found himself talking to the Keystone Paper Cylinder Company and asked to speak to Lewis Ehler.

'Whom shall I say is calling?' said the receptionist.

'Just tell him it's Jack, calling about his email.'

Ehler came on right away. He spoke in a wheezy, high-pitched voice accelerating steadily in an urgent whisper.

'Thank you so much for calling. I've been half out of my mind not knowing what to do. I mean, since Mel's been gone I've—'

'Whoa, whoa,' Jack said. 'Gone? Your wife's missing?'

'Yes! Three days now and—'

'Wait. Stop right there. We can save me time and you a lot of breath: I don't do missing wives.'

His voice rose in pitch and volume. 'But you must!'

'That's a police thing. They've got the manpower and resources to do missing persons a lot better than I ever