Now, everyone knows how Anger feels—or Pleasure, Sorrow, Joy, and Grief —yet as Alexander Pope suggests in his Essay on Man, we still know almost nothing about how those processes actually work.

“Could he, whose rules the rapid comet bind, Describe or fix one movement of his mind? Who saw its fires here rise, and there descend, Explain his own beginning, or his end?” How did we manage to find out so much about atoms and oceans and planets and stars—yet so little about the mechanics of minds? Thus Newton discovered just three simple laws that described the motions of all sorts of objects, Maxwell uncovered just four more that explained all electro-magnetic events—and Einstein then reduced all those laws into yet smaller formulas. All this came from the success of those physicists’ quest: to find simple explanations for things that, at first, seemed extremely complex.

Then, why did the sciences of the mind make less progress in those same three centuries? I suspect that this was largely because most psychologists mimicked those physicists, by looking for equally compact solutions to questions about mental processes. However, that strategy never found small sets of laws that accounted for, in substantial detail, any large realms of human thought. So this book will embark on the opposite quest: to find more complex ways to depict mental events that seem simple at first!

This policy may seem absurd to scientists that have been trained to believe such statements as, “One should never adopt hypotheses that make more assumptions than they need.” But it is worse to do the opposite—as when we use ‘psychology words’ that mainly hide what they try to describe. Thus, every phrase in the sentence below conceals its subject’s complexities:

You ‘look at an object and see what it is.

For, ‘look at’ suppresses your questions about the systems that choose how you move your eyes. Then, ‘object’ diverts you from asking about your visual systems partition a scene into various patches of color and texture—and then assign them to different ‘things.’ And, ‘see what it is’ sidesteps all the questions you could ask about how that sight might be related to other things that you’ve seen in the past.

It is much the same for the commonsense words that we usually use to talk about what our own minds do, as when one makes a statement like, “I think I understood what you said.” For perhaps the most extreme example of this is how we use words like Me and You—because we all grow up with this fairy-tale:

We each are constantly being controlled by powerful creatures inside our minds, who do our feeling and thinking for us, and make our important decisions for us. We call these our Selves or Identities—and believe that they always remain the same, no matter how we may otherwise change.

This “Single-Self” concept serves us well in our everyday social affairs. But it hinders our efforts to think about what minds are and how they work—because, when we ask about what Selves actually do, we get the same answer to every such question:

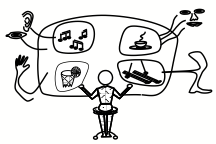

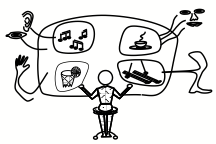

Your Self sees the world by using your senses. Then it stores what it learns in your memory. It originates all your desires and goals—and then solves all your problems for you, by exploiting your ‘intelligence.’

A Self controlling its Person’s Mind

What attracts us to this queer idea, that we don’t make any decisions ourselves but just delegate them to something else? Here are a few kinds of reasons why a mind might entertain such a fiction:

Child Psychologist: Among the first things you learn to recognize are the persons in your environment. In your next stage, you should assume that you are also a person, too. But perhaps it is easier to conclude that there is a person inside of you.

Therapist: Although it’s a legend, it makes life more pleasant—by keeping us from seeing how much we’re controlled by conflicting, unconscious goals.

Pragmatist: That image makes us efficient, whereas better ideas might slow us down. It would take too long for our hard-working minds to understand everything all the time.

However, although the Single-Self concept has practical uses, it does not help us to understand ourselves—because it does not provide us with smaller parts we could use to build theories of what we are. When you think of yourself as a single thing, that gives you no clues about issues like these:

What determines the subjects I think about?

How do I choose what next to do?

How can I solve this difficult problem?

Instead, the Single-Self concept only offers useless answers like these:

My Self selects what to think about.

My Self decides what I should do next.

I should try to make Myself get to work.

Whenever we wonder about our minds, the simpler are the questions we ask, the harder it seems to find answers to them. When you are asked about some difficult task like, “How could a person build a house,” you might answer almost instantly, “Make a foundation and then build walls and a roof.” However, one can scarcely imagine what to say about seemingly simpler questions like these:

How do you recognize things that you see?

How do you comprehend what a word means?

What makes you like pleasure more than pain?

Of course, none of those questions are simple at all. The process of ‘seeing’ a car or a chair uses hundreds of different parts of your brain, each of which does some quite difficult jobs. Then why don’t we sense that complexity? That’s because many processes that are most vital to us have evolved to work inside parts of the brain that have come to function so ‘quietly’ that the rest of our minds have no access to them. This could be why we find it so hard to explain many things we find so easy to do.

In Chapter §9, we’ll come back to that Self—and argue that this, too, is a very large and complicated structure.

Whenever you think about your “Self,” you are switching among a huge network of models,