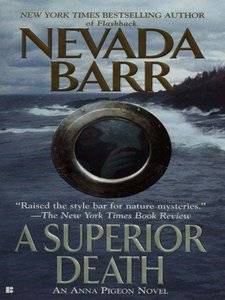

Nevada Barr

A Superior Death

The second book in the Anna Pigeon series, 1994

ONE

These killers of fish, she thought, will do anything. Through the streaming windscreen Anna could just make out a pale shape bobbing in two-meter waves gray as slate and as unforgiving. An acid-green blip on the radar screen confirmed the boat’s unwelcome existence. A quarter of a mile to the northeast a second blip told her of yet another fool out on some fool’s errand.

She fiddled irritably with the radar, as if she could clear the lake fog by focusing the screen. Her mind flashed on an old acquaintance, a wide-shouldered fellow named Lou, with whom she had argued the appeal-or lack thereof-of Hemingway. Finally in frustration Lou had delivered the ultimate thrust: “You’re a woman. You can’t understand Papa Hemingway.”

Anna banged open her side window, felt the rain on her cheek, running under the cuff of her jacket sleeve. “We don’t understand fishing, either,” she shouted into the wind.

The hull of the Bertram slammed down against the back of a retreating swell. For a moment the bow blocked the windscreen, then dropped away; a false horizon falling sickeningly toward an uncertain finish. In a crashing curtain of water, the boat found the lake once more. Anna swore on impact and thought better of further discourse with the elements. The next pounding might slam her teeth closed on her tongue.

Five weeks before, when she’d been first loosed on Superior with her boating license still crisp and new in her wallet, she’d tried to comfort herself with the engineering specs on the Bertram. It was one of the sturdiest twenty-six-foot vessels made. According to its supporters and the substantiating literature, the Bertram could withstand just about anything short of an enemy torpedo.

On a more kindly lake Anna might have found solace in that assessment. On Superior ’s gun-metal waves, the thought of enemy torpedoes seemed the lesser of assorted evils. Torpedoes were prone to human miscalculation. What man could send, woman could dodge. Lake Superior waited. She had plenty of time and lots of fishes to feed.

The

She braced herself between the dash and the butt-high pilot’s bench and picked up the radio mike. “The

Not for the first time Anna marveled at the number of boaters who survived Superior each summer. There were no piloting requirements. Any man, woman, or child who could get his or her hands on a boat was free to drive it out amid the reefs and shoals, commercial liners and weekend fishing vessels. The Coast Guard’s array of warning signs-Diver Down, Shallow Water, Buoy, No Wake-were just so many pretty wayside decorations to half the pilots on the lake. “Go to six-eight.” Anna switched her radio from the hailing frequency to the working channel: “Affirmative, it’s me over here. I’m going to come alongside on your port side. Repeat: port side. On your left,” she threw in for good measure.

“Um… ten-four,” came the reply.

For the next few minutes Anna put all of her concentration into feeling the boat, the force of the engines, the buck of the wind and the lift of the water. There were people on the island-Holly Bradshaw, who crewed on the dive boat the

She missed Gideon, her saddle horse in Texas. Even at his most recalcitrant she could always get him in and out of the paddock without risk of humiliation. The

The

I’ll never be an old salt, Anna told herself. Sighing inwardly, she pushed right throttle, eased back on left, and sidled up behind the smaller boat. Together they sank into a trough.

The

Two men, haggard with fear and the ice-slap of the wind, slogged through the bilge to grapple at the

There was a creak of hull against hull as they jerked the boats together, undoing her careful maneuvering.

The man at the bow, wind-whipped in an oversized K-mart slicker, dragged out a yellow nylon cord and began lashing the two boats together as if afraid Anna would abandon them.

She shut down to an idle and climbed up the two steps from the cabin. The fisherman at the

“Untie that,” she shouted against the wind. “Untie it.” The man, probably in his mid-forties but looking older in a shapeless sweatshirt and cap with earflaps, turned a blank face toward her. He stopped tying but didn’t begin untying. Instead he looked to his buddy, still wrapping loops of line round and round the bow cleats.

“Hal?” he bleated plaintively, wanting corroboration from a proper authority.

Anna waited, her hands on the

Hal finished his pile of Boy Scout knots and made his way back the length of the boat. He was younger than the man white-knuckling the stern line, maybe thirty-five. Fear etched hard lines around his eyes and mouth but he