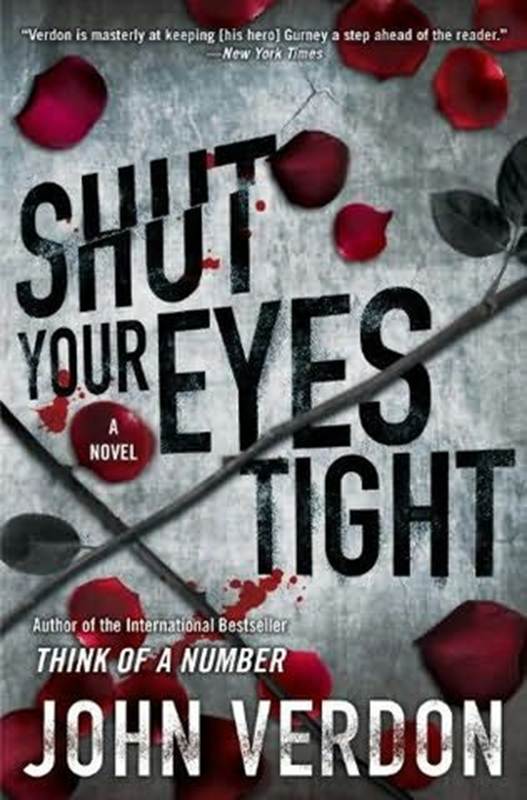

John Verdon

Shut Your Eyes Tight

The second book in the Dave Gurney series, 2011

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1

There was a stillness in the September-morning air that was like the stillness in the heart of a gliding submarine, engines extinguished to elude the enemy’s listening devices. The whole landscape was held motionless in the invisible grip of a vast calm, the calm before a storm, a calm as deep and unpredictable as the ocean.

It had been a strangely subdued summer, the semi-drought slowly draining the life out of the grass and trees. Now the leaves were fading from green to tan and had already begun to drop silently from the branches of the maples and beeches, offering little prospect of a colorful autumn.

Dave Gurney stood just inside the French doors of his farm-style kitchen, looking out over the garden and the mowed lawn that separated the big house from the overgrown pasture that sloped down to the pond and the old red barn. He was vaguely uncomfortable and unfocused, his attention drifting between the asparagus patch at the end of the garden and the small yellow bulldozer beside the barn. He sipped sourly at his morning coffee, which was losing its warmth in the dry air.

To manure or not to manure-that was the asparagus question. Or at least it was the first question. If the answer turned out to be yes, that would raise a second question: bulk or bagged? Fertilizer, he had been informed by various websites to which he’d been directed by Madeleine, was the key to success with asparagus, but whether he needed to supplement last spring’s application with a fresh load now was not entirely clear.

He’d been trying, at least halfheartedly, for their two years in the Catskills to immerse himself in these house- and-garden issues that Madeleine had taken up with instant enthusiasm, but always nibbling at his efforts were the disturbing termites of buyer’s remorse-remorse not so much at the purchase of that specific house on its fifty scenic acres, which he continued to view as a good investment, but at the underlying life-changing decision to leave the NYPD and take his pension at the age of forty-six. The nagging question was, had he traded in his first-class detective’s shield for the horticultural duties of a would-be country squire too soon?

Certain ominous events suggested that he had. Since relocating to their pastoral paradise, he had developed a transient tic in his left eyelid. To his chagrin and Madeleine’s distress, he had started smoking again sporadically after fifteen years of abstinence. And, of course, there was the elephant in the room-his decision to involve himself the previous autumn, a year into his supposed retirement, in the horrific Mellery murder case.

He’d barely survived that experience, had even endangered Madeleine in the process, and in the moment of clarity that a close encounter with death often provides, he had for a while felt motivated to devote himself fully to the simple pleasures of their new rural life. But there’s a funny thing about a crystal-clear image of the way you ought to live. If you don’t actively hang on to it every day, the vision rapidly fades. A moment of grace is only a moment of grace. Unembraced, it soon becomes a kind of ghost, a pale retinal image receding out of reach like the memory of a dream, receding until it becomes eventually no more than a discordant note in the undertone of your life.

Understanding this process, Gurney discovered, does not provide a magic key to reversing it-with the result that a kind of halfheartedness was the best attitude toward the bucolic life that he could muster. It was an attitude that put him out of sync with his wife. It also made him wonder whether anyone could ever really change or, more to the point, whether

The bulldozer situation was a good example. He’d bought a small, old, used one six months earlier, describing it to Madeleine as a practical tool appropriate to their proprietorship of fifty acres of woods and meadows and a quarter-mile-long dirt driveway. He saw it as a means of making necessary landscaping repairs and positive improvements-a good and useful thing. She seemed to see it from the beginning, however, not as a vehicle promising his greater involvement in their new life but as a noisy, diesel-stinking symbol of his discontent-his dissatisfaction with their environment, his unhappiness with their move from the city to the mountains, his control freak’s mania for bulldozing an unacceptable new world into the shape of his own brain. She’d articulated her objection only once, and briefly at that: “Why can’t you just accept all this around us as a gift, an incredibly beautiful gift, and stop trying to

As he stood at the glass doors, uncomfortably recalling her comment, hearing its gently exasperated tone in his mind’s ear, her actual voice intruded from somewhere behind him.