The satin lining was green-Josh's favorite color-and the skeleton nestled there was the same red cast as the jawbone outside on the porch. The hands and feet were missing. Perhaps the judge's night visitor was an amateur at exhumation and had overlooked remains that might pass for sticks and stones. What destroyed Oren was the slight overlap of the skull's front teeth, the only physical imperfection of a fifteen-year-old boy.

Hannah stepped back from the coffin. 'You wouldn't expect bones to smell.'

By profession, Oren was accustomed to decomposition. He knew it was the confined space and the seal of the coffin that gave the bones the reek of an ossuary. And there was also an earthy smell. He leaned down, as if to kiss his brother's lipless face. 'Hannah. Did the judge clean the skull? Did he do anything to it before it went into the coffin?'

'No, not a thing. The way Josh is now-that's the way he came home.'

The bones of the body were dusted with soil, but the skull bore the circular marks of cloth-wiped dirt. No part of the skeleton showed signs of exposure to the elements, and there was no damage from the fangs of animal predators-only the stains of sheltering earth.

Raw burial could only be read as murder.

The torso and limbs were more lightly colored than the skull, a sign that they had been protected for a time by a layer of clothing. Oren took small comfort in the knowledge that his little brother had not been thrown naked into some hole.

Hannah tugged at his sleeve. 'The judge won't want to give Josh up to the sheriff, but he might be willing to part with one or two bones.'

Oren nodded, as if she had said something sensible. It had been easy enough for the judge to part with his firstborn son. But it would be too hard on the old man to give up the other child, the dead one.

Hannah raised one finger to herald another thought. 'Maybe we could just hold off on reporting Josh's skeleton-at least until it's finished.' One hand went up to her mouth to stifle any more mad ideas. Her head tilted to one side, as if to shake out this contagion of an old man's insanity, and then she gripped Oren's arm. 'Before you call the sheriff, you have to prepare the judge.'

And how would he convince a crazy old man to surrender his dead son? Well, he would avoid any useless words like

Hannah stepped up to perform this small service for him. She was lowering the lid when he said, 'Wait!' and stayed her hands. 'They don't match up.'

'What?'

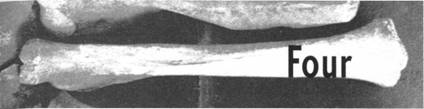

'Look at the thigh bones, Hannah.'

She leaned over the coffin to stare at one and then the other. She looked up at him, quizzical-worried. 'They're the same.'

'Look again. The left one's off by an inch. Now look at the arms.' He pointed to radials and femurs, not wanting to touch them. 'These bones belong to two different skeletons… at

4

After returning the telephone's receiver to its antique cradle, Oren knew he could count on thirty minutes, maybe a solid hour, before a deputy was dispatched from the county seat. There would be no sirens screaming, no haste. The deputy from Saulburg might even stop for breakfast along the way. The County Sheriff 's Office was long accustomed to similar reports from hikers in the woods, and the remains always turned out to be the bones of animals. Oren had made no mention of the skeleton in the coffin-only the jawbone, but not its dental filling.

He climbed the stairs and returned to his old bedroom, drawn there by the photograph in the silver frame, the shot taken on the day Josh had vanished. That was the only time that his little brother had used a tripod, the only instance of Josh appearing in one of his own pictures. Among the hundred examples of his brother's work on all the walls of the house, this posed composition was a rarity. The boy had favored a handheld camera for candid shots taken on the fly-hit and run. In this picture, there was more than a foot of distance between Oren and his brother, as if Josh were already leaving him in that moment.

Other photographs, more than a dozen, hung on the bedroom walls, and they chronicled five years of Josh's love affair with the camera. Oren stared at his favorite, one of himself and a girl who had only appeared in the summers of his boyhood. He colored her black-and-white image with a memory of long red hair and eyes the color of dark honey. As a boy, he had availed himself of furtive glances to count the freckles on her nose. At the age of twelve, this had been his life's work. In his early teens, he had progressed to a fascination with her red toenail polish.

He might have been thirteen years old when this shot was taken. Boy and girl were pictured walking away from one another, heading toward opposite ends of the frame. Between them yawned a great empty space- nothing but sky. His little brother had never taken a picture without the intention to tell a story or a joke, and this was both. Nothing had ever happened between Oren and the summer girl. They had not exchanged a single word. He had never heard the sound of her voice.

'Isabelle Winston.'

'Hannah, don't

She should know better. Creeping up behind people had always been the judge's job. Oren turned around to see the housekeeper eyeing the same photograph. How long had she been standing there?

'Josh was good, wasn't he?' She moved closer to the wall. 'A real artist.'

Oren reached out to the bureau and picked up her homecoming gift, the picture of two brothers. 'I know this shot came from Josh's last roll of film, the one he left behind that day. When was this developed? Was it before or

'You make it sound like he kicked you out of the house.' She smiled, taking no offense at his tone of interrogation. 'After Josh went missing, I found a roll of film stashed in his sock drawer. I left it there for a while. The judge didn't want anything disturbed in your brother's room. He had a real bug about that. I don't remember exactly when I took the roll down to the drugstore to get it developed.' After a furtive glance at the door, she lowered her voice. 'The judge doesn't need to know I did that. He'd pitch a fit.' Hannah gave him her best conspirator's grin. 'So don't you rat on me, okay?' She returned the photograph to the bureau. 'It's a good picture, but I know Josh would've done a better job in his own darkroom.'

'That's still in the attic?'

'Just the way he left it.'

'Is that where you put the rest of the pictures from his last roll?'

Hannah turned to the window. 'There's a car coming.'

He did not doubt her, but a few moments passed before he also heard the sound of tires on the gravel driveway. At the hour of a shift change, there would be no deputies on duty in this area, and it was too soon for any official vehicle from Saulburg.

The owner of the pickup truck had streaks of blond hair the light shade of a towhead child's. If Hannah Rice had been in a more charitable mood, she might have credited those highlights to the sun instead of vanity. 'The judge says you have to wait until that warrant shows up.'

Dave Hardy was hunting for a shovel amid the pile of bags and gardening tools in the bed of his truck. 'I give the orders, Hannah.'

'Sure you do.' She was not convinced that anyone in a rock-'n'-roll T-shirt and blue jeans could have any authority over her; though, even out of uniform, everything about this man announced him as an officer of the law.

His I-run-the-show attitude had begun to form at the age of eight when he got his first pair of dark glasses. Dave had worn them even in the rain, and some people who had watched him grow up could no longer recall the color of his eyes. When Hannah thought of this man as a child, she always embellished this picture of him with a tiny, fully loaded gun. Today he was not carrying a weapon, and, without his dark glasses, he looked nearly naked. Obviously feeling the need to bolster his credibility with her, he clipped his deputy's star to a belt loop, and then he resumed the chore of ransacking his pickup truck.

The retired judge sat on the porch steps beside Josh's jawbone. Hannah leaned down and lightly touched his arm, her prelude to every strong suggestion. 'If you'd just tell Dave what's upstairs in that coffin, he might lose interest in that patch of dirt.' She jabbed her thumb in the direction of freshly turned earth at the end of the garden, where the judge had planted his last batch of bulbs.

Henry Hobbs shook his head. No deal. He called out to the deputy, 'For the last time-the bone didn't come from my garden!'

'We'll see.' Triumphant, Dave Hardy raised a shovel high above his head. 'Found it.' He climbed down from the truck bed, turned toward the house-and turned to stone.

Hannah looked back over one shoulder to see what had stunned the deputy. Oren stood in the open doorway, only curious at the moment and relaxed in his stance.

The deputy could only stare at him, but everyone stared at Oren Hobbs. It was not merely the good looks of her blue-eyed boy that drew this kind of attention-more like attraction with the pull of gravity. Twenty years ago, in Hannah's estimation, Oren had been interrupted on the way to becoming somebody. She had never forecast the Army in his future. No, she had always seen him at the center of a stage. Indeed, this morning, it was almost like a performance, him standing there, hands in his pockets, wrapped in the aura of a rock star in an idle moment. His audience, Dave Hardy, was spellbound.

Spell undone, Dave rolled back his shoulders and gripped the shovel in both hands. 'Odd thing, Oren-that jawbone showing up the same time you do.'

The judge rose from the porch steps and walked toward the deputy, eyes on the shovel. 'You can't dig up my garden. Those bulbs will never bloom if you-'

'That's enough, old man.' Dave freed up one hand to point at the porch. 'Now go back and sit down. That's an

The whites of Hannah's eyes got wider. One did not disrespect Judge Henry Hobbs-not in

Dave marched toward the far end of the flower bed and never saw his predictable demise in the eyes of Oren Hobbs, who descended the porch steps-slowly-angry and focused on the deputy.

Poor deputy.

Hannah Rice had always loomed large and mighty, even after Oren and Josh had grown taller than she was. The slightest pressure of the housekeeper's hand on any part of a boy that she could catch had been enough to restrain the two youngsters. And this influence of hers had lasted into their teenage years. It simply had never occurred to either of them that, once caught, they could ever get away from her.

And now he felt Hannah's small hand closing over his right fist, the one he favored for beating the crap out of Dave Hardy. Oren stood very still, powerless to go anywhere. He looked down to catch her brief smile, the equivalent of rolling up her sleeves in anticipation of doing some damage.

Hannah trained her eyes on the deputy and worked her old magic, hurling words across the length of the flower bed with the crack of lightning bolts. 'Put that shovel down this

Dave looked up. The shovel hovered.

The housekeeper lowered her voice for the next salvo. 'Don't you make me call your mother.'