Furrow. Tilt. Nervous smile.

I repeat what I’d said slowly in more basic terminology and act out the parts about the taking of the pictures and the necking. Her eyes widen.

“Then, you take the pictures, text them to your lawyer, and BAM! Money.” Here I rub three fingers across my thumb in the international signal for “mucho dinero.”

Her brow unfurrows, her head untilts, and she sighs, wishing desperately she could litigate a divorce in New York City. As it stands, they just live separately from each other and Yoko does what she can to bleed him dry of his and his secretary’s funds.

She lives in Kamiooka with her twenty-eight-year-old daughter, Fumiko. Both of them are currently studying to be Japanese language instructors, and they are nearing the completion of their course.

“Oh,

I feel like I’ve started to develop a special closeness with Yoko, one that transcends the confines of our cramped classroom. We’ve discussed her marriage, her business, and Fumiko, whom she fears is too awkward to ever marry and will live with her forever. Could I maybe take things to the next level and ask her to be my Japanese teacher?

“You know, I am very interested in studying the language.”

She says, “

” reverting back to Japanese. “Really?” She pauses. “We can to teach you.”

Yessssss. And, better yet:

“We do for free, because these days we cannot charge for to teaching. Not yet get certificate.”

Now, if I were the uncertified teacher, I wouldn’t likely be paying much attention to such an inconvenient rule, but this is a good example of the tendency of many Japanese towards being honest and law-abiding. There are, of course, exceptions, like, I don’t know, the Japanese mafia, whose hobbies include getting ungainly tattoos, carrying automatic weapons, and using their chopsticks to put a person’s eyes out, but generally, the Japanese respect the rules, as opposed to Westerners who would cheat their own mothers if it meant turning a profit.

So on a Wednesday evening a few weeks later, I meet Yoko and Fumiko out on the street in front of the school, and they lead me to their home behind the Keikyu plaza, high up on top of a very, very steep hill. For the first time since my arrival here, I realize how deeply disappointed I am that my fantasy of traveling hither and yon (mainly yon) upon a moving sidewalk conveyor has not been realized.

They live on the fifth floor of a giant condominium complex with a lot of security cameras and electronic checkpoints. The little area outside their door is full of Disney garden figurines: the Seven Dwarves, Bambi, Thumper, Daisy, Cinderella’s mice, and, inexplicably, the Tasmanian Devil. We go inside, relieve ourselves of our footwear, and Yoko leads me to the dining room table, where we will be doing our studying.

It’s a cozy condo. The hallway leads to a tiny kitchen on the left, opening into a dining area straight ahead with a finished wooden table and flanked by a china cabinet full of tiny Japanese bowls and cutlery and a few muted watercolors decorated with swirls of calligraphy. Beyond this is a small sitting room. And the Disney theme continues. A piano stands on the left wall, and next to it is a large shelf full of Disney sheet music and Seven Dwarves tea tins. A big framed puzzle of Cinderella, the Fairy Godmother, and the newly transmogrified pumpkin coach hangs above the piano.

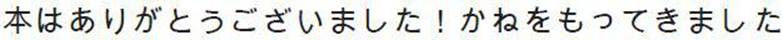

On the dining table are two books:

Since I’ve already done a little studying on my own in preparation for my lessons, I decide I’ll be clever and thank them for buying me the books and explain that I have some money to pay them, all in Japanese. I practice a few times silently before taking the plunge and adding some vocal cords.

“

,” I say to Yoko when she walks into the room. “Thank you for the books. I’ve brought some money.”

“

,” she corrects me, wincing and giggling.

It’s amazing the difference one little omitted syllable can make. She shakes her head and waves her hand like she’s sending away a bad smell.

I read in one of Ewan’s books that the syllable “o” is an honorific, placed in front of some words to make them softer or more polite. I’d omitted it in front of the word “money,” and this omission had drastically altered the sound of the sentence, judging from Yoko’s reaction. So instead of saying, “Thank you so much for the books. I’ve brought some money,” I’d actually said something like, “Here’s your money, you greedy bitch. Thanks a fucking lot.”

It is this kind of tiny but pivotal error that seems so easy to make on a regular basis when trying to communicate in Japanese as a foreigner. When learning a new language, especially one completely unconnected to your mother tongue and filled with such contextual nuance, you’re naked, totally unprotected, walking blind in a brambly and treacherous terrain full of colloquialisms, multiple meanings, varying levels of politeness, and double entendres. I am terrified that one day, while trying to tell someone they look nice, I’ll instead end up saying I want to lick their daughter’s underarms. I’m about to learn what it’s like to be the student crying over his textbook and not the teacher laughing up his sleeve.

Here’s the thing: if you’re going to learn a new language, you’ve got to be unafraid to make mistakes, relax, and have fun. What I tell my students, in other words. I’d thought I’d been blowing out a bunch of useless hot air, but turns out I was wise beyond my own understanding.

During the lesson, I sit at the dining room table with my notebook and books in front of me while Yoko and Fumiko team-teach me. They stand on each end of a dry-erase board that they’ve wheeled into the room, and both hold large wooden pointers for easier gesturing. Fumiko, a giggly gal with a frizzy bob, proves herself quite the opposite of her exceptionally put-together mother. She dresses in sweats, doesn’t bother with makeup, and laughs loudly with her mouth wide open-a no-no for women in Japan. Once, at Yoko’s prompting, she covers her mouth and nearly succeeds in knocking a tooth out with her large wooden pointer.

She drills me on basic pronunciations of the phonetic characters and some simple words and phrases, playfully jabbing me with the pointer whenever I make a mistake. Yoko then takes the reins and corrects my mistake, making me repeat after her until I get it right or I feel like I’m losing my mind, whichever comes first.

Yoko: KonNIchiwa

Me: Konichywa

Yoko: No, no. Konnichiwa

Me: Konichywa

Yoko: Kon-NI-chi-wa

Me: Konichywa

Fumiko: KON-NI-CHI-WA!! [jab with wooden pointer]

Me: Konnichiwa!

Everyone: [applause]

The ladies escort me through the wonderland that is basic, bottom-rung, just-off-the-boat Japanese, from the different greetings for the different times of day, to expressions for politely leaving work before someone else, expressions for politely refusing more food, expressions for politely asking where the toilet is, expressions for politely requesting something in a restaurant, expressions for politely saying no, you would rather not eat pizza for dinner because you had that shit for lunch, and about what seems like hundreds of different ways of apologizing for what seems like a hundred different things I didn’t realize I could do wrong. We cap things with a session about useful expressions to use when riding in a taxi: saying where you need to go, where to stop, giving directions to a driver, and such. All in all I do pretty well, with a few minor exceptions hardly worth mentioning.

Yoko/Taxi Driver: Where would you like to go?

Me: Can you please take me to the park? First, drive straight. And then take a left at the next stoplight. After that, go straight.

Y/TD: OK, I understand.