through a gauntlet of spit and hatred, he’d had letters which started in a variety of ways: “Mr. Avery” from his hopeless cut-rate solicitor, “Dear Son” from his hopeless cut-rate mother, “You fucking piece of shit”—or variations on the theme—from many hopeless cut-rate strangers.

The thought gave him a pang. “Dear Mr. Avery” made him think of gas bills and insurance salesmen and Lucy Amwell who’d gone off half-cocked trying to organize a school reunion, like they’d all grown up in California instead of a smoggy dump in Wolverhampton. But still, they were people who’d wanted to be nice to him and interact with him without judging and whining and grimacing with that cold look of disgust they couldn’t hide.

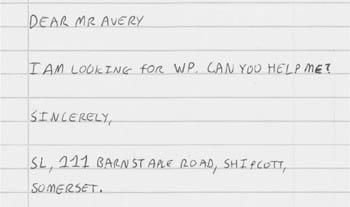

Dear Mr. Avery. That was who he really was! Why couldn’t other people see it? He read it again.

If Arnold Avery had had a cellmate, he would have been struck by the total stillness that descended suddenly on this slightly built killer of small and helpless things. It was a stillness more marked even than sleep—as if Avery had slipped rapidly into a coma and the world was turning without him. His pale green eyes half closed and his breathing became almost imperceptible. That cellmate would also have seen Avery’s sun-starved skin break out in goose-flesh.

But if the hypothetical cellmate had been privy to the workings of Avery’s brain he might have been shocked by the sudden surge in activity.

The carefully hand-printed words on the page had exploded in Avery’s brain like a bomb. He knew who WP was, of course, just as he knew MO, and LD, and all the others. They were triggers in the loaded gun of his mind, which he could use to fire off streams of exciting memories whenever he wanted. His brain was a filing cabinet of useful information. Now, as his body shut down to allow his mind to work more efficiently, he allowed himself to slide open the drawer marked WP and to peer inside—something he had not done for some years.

WP was not his favorite. Generally he used MO or TD; they had been the best. But WP was not to be sniffed at and, inside that mental drawer, Avery hoarded a wealth of information gleaned from his experience, from newspaper and TV reports of the child’s disappearance, and, later, from his own trial which had been moved to the picturesque Crown Court in Cardiff—supposedly to give him a fighting chance, which was laughable, when you thought about it.

William Peters, aged eleven. Fair hair in a fringe over dark blue eyes, pink cheeks on pale skin, and—for a short while—a grin that almost swallowed his ears it was so wide.

Avery had stopped at the crappy little village shop. He’d bought a ham sandwich because burying Luke Dewberry had been hungry work. Out of habit, he’d glanced at the local paper, the

Local papers were a rich source of information for a man like him. They were filled with photos of children. Children dressed as pirates for charity; children who had won silver medals at national clarinet competitions; children who had been picked for the Under-13s even though they were only eleven; whole teams of children in soccer or cricket or running kit, each with his or her name conveniently printed in the caption below. Sometimes he would call them, pretending to be another reporter wanting the story for another newspaper. It was so easy. Bigheaded parents were only too happy to milk their child’s paltry success and would hand over the phone. Only rarely did they snatch the phone from their child’s ear in time—alerted by the confused shock on a young face.

Sometimes he just used a child’s name and details to strike up conversation with random kids in parks and playgrounds. “How old are you? You must know my nephew, Grant? The one who just got the lifesaving award, you know? Yeah, that’s right. I’m his uncle Mac.” And he’d be off.

Anyway.

He’d just got back in his van with the sandwich when he saw William Peters—Billy, his mother called him later in the papers—go into the shop. Avery only caught a fleeting glimpse of Billy but it was worth waiting until he came out, he thought. He ate the ham sandwich while he did just that. He hadn’t bought the

The boy took a while and when he came out, Avery knew.

Now, all these years on, Avery still managed to recapture some of the thrill of that moment when he identified a target. The way he hardened, and spit filled his mouth, so that he had to swallow to keep from drooling like an idiot.

Billy was kind of on the thin side, but he had a little-boy jauntiness that was very appealing. He walked away from Avery’s van, blissfully unaware that he’d just chosen the last meal of his young life—a bag of Maltesers. It made Avery smile to watch the child swagger down the street, crunching on his sweets, kicking a plastic milk bottle along the gutter. He liked a confident child; a confident child was far more likely to be eager to help—to lean through the window just that little bit farther …

He put the van into gear and rolled down the street, pulling his map towards him …

Avery shivered.

“Goose walk over your grave?”

Officer Ryan Finlay leered through the hatch at Avery, his drinker’s nose poking into Avery’s space; his watery blue eyes darting about. The killer in the cell felt himself knot inside with hatred.

“Officer Finlay. How are you?”

“Right enough, Arnold.”

Avery hated him some more.

Arnold.

As if they were old friends. As if one night soon Ryan Finlay might crook an arm at him at lockup and say, “Come on, lad, let’s you and me put a couple away down the Keys.” As if Avery might even enjoy the craic, sipping a black and tan, surrounded by a forest of thick-necked, thick-headed screws talking about how hard it was to lock and unlock doors and shepherd docile thieves between floors.

“Anything interesting?” Finlay nodded at the letter in Avery’s hands. In that instant, Avery knew that Finlay had already read it, that Finlay had been disappointed at being unable to stick his thick black pen through anything in it, and that this question now was a clumsy attempt to probe for the information he knew must somehow be contained therein.

“Just a letter, Officer Finlay.”

“While since you had one, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is.”

“Well, that’s nice.”

“Isn’t it?”

Finlay took a moment to think of his next lumbering line of attack.

“News from home?”

“Yes.”

Again Finlay was momentarily lost. He took his time picking something troublesome out of his left nostril. Avery controlled himself admirably.

“What’s happening there, then?”

While Finlay had picked his nose, Avery had anticipated this very question and prepared for it in full.

“Nothing special. My cousin. He’s a computer nut. I had an old word processor—an Amstrad. He says it’s a collectable or some such. Always trying to get it off me.”

“Geek, is he?”

“A geek. That’s right.”

Finlay looked around, acting casual. “You going to let him have it?”

Avery shrugged. Then he smiled, putting everything into it. “We’ll see.”

Finlay was a prison officer with twenty-four years on the job, but in the face of that smile his suspicion melted away and he couldn’t help feeling that he and Avery suddenly shared some secret that was really quite wonderful.

Finlay had interrupted his train of thought, but that was good, really. That train was too good to stop in daylight. It was a nighttime train, though not a sleeper. He smiled inwardly at that. He’d go back over WP tonight;