right now he was interested in the possibilities that this odd little letter represented. Possibilities were the first casualty of prison life. They were curtailed as soon as the cell door clanged. And for most prisoners they would never be properly recovered. Even men who served only months or a few years suddenly discovered that the possibilities in their lives had been confiscated like shoelaces. Before they had hoped for office jobs, now they could expect only laboring or the dole. Cons lived by a whole different concept of possibility. For lifers, possibilities came to mean even smaller things: the possibility of chips instead of mash, chops instead of mince.

Avery didn’t know who SL was, but for clarity he decided to think of SL as male.

SL had been very careful about this letter. He’d been smart enough to realize or to learn that letters did not pass to and from pedophiles and serial killers without the busy pen of the censor crawling all over them. So he’d kept it short and cryptic. He’d also been smart enough to know that bare initials would mean something to Avery.

But of course, the return address was the giveaway. When he’d first been incarcerated, Avery had had dozens of letters from in and around Shipcott. Most had been insulting or pleading, and those were easily forgotten, but he’d had one from Billy Peters’s sister, if memory served (as it would have to—he’d not been allowed to keep his huge volumes of correspondence). It was the usual thing—wanting to know what had happened to Billy; where he was buried. She had begged Avery to put her mother out of her misery. He’d written back pointing out the charming coincidence—that Billy had begged him to do the same for him.

Avery seriously doubted that Billy Peters’s sister had ever got that letter. This conviction was strengthened by the fact that a day after he put it in the prison mail, he found himself led to the B-wing showers. The screws had told him that the Segregation showers were being replumbed. The issue of plumbing with its accompanying vocabulary of pipes, bores, and plungers seemed to amuse both the screws quite a lot on the way to B-wing, and once they’d left him in the showers—naked but for his shitty flannel-sized prison-issue towel—he’d understood why.

He’d been in the hospital for two weeks—the first of them facedown.

Ironically, just two years ago the showers in the Vulnerable Prisoners Unit here at Longmoor really had been renovated; Avery had declined to bathe for the twelve days the job took to complete.

And, for Avery, that was a serious decision.

Arnold Avery hated to be dirty. Hated it like the plague. Sometimes just being touched by another prisoner or screw could send him hurrying to the shower room to scrub his clothes and his skin.

After each murder—and each burial—he’d had to scrub and scrub.

Cleanliness was next to godliness.

Strangulation was as clean as he could make it, but still—some of them vomited, some of them pissed in terror, some of them did worse than that. And when they did, disgust doused his passion and made him hate them all the more for ruining the experience for him. On more than one occasion he’d had to hose them down before he could bear to finish them off.

And once they were dead, they repulsed him. Even the helpless tears that got him so hot while they were alive became slimy trails of disgust on their cooling faces.

Anyway.

He couldn’t be certain, but he thought it quite possible that the letter from WP’s sister had come from the same address: 111 Barnstaple Road, Shipcott.

So, SL was who? A crusading neighbor? WP’s mother? A cousin? A grandchild? Another, much later, son or daughter conceived in an effort to create a new family to fill the black hole which the last one had become? Avery mused momentarily, but they all seemed equally possible so he didn’t waste too much time.

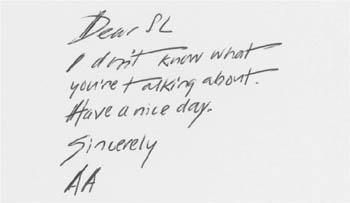

“Dear Mr. Avery” was good. “WP” was good. The appeal for help was nice and to the point.

But what really impressed Arnold Avery was the word “Sincerely.”

The first letter Steven Lamb wrote to Arnold Avery had been returned to him so blotted by thick black felt tip that it was unreadable. The censor had finally given up three quarters of the way through and had not even passed it on to the prisoner. He had merely scrawled “Unacceptable” across the last quarter of the letter and sent it back to Shipcott.

Steven was humiliated. He felt like a little kid who had been caught sneaking into an 18 film in a false moustache.

It was days before he forgave himself and regained the confidence to make another attempt. He was only twelve, he reasoned; he couldn’t be expected to get stuff like writing to serial killers right the first time.

Over the next week he composed the letter again and again in his mind, each time paring and shaving and whittling until he decided to start from the other end of the scale of information required. That resulted in the first 90 percent of the letter.

What took him another two weeks to wrestle with was whether to use “Yours sincerely” or “Yours faithfully.”

Although this was a personal letter where the name of the intended recipient was known to him, “Yours sincerely” stuck in Steven’s craw. He just couldn’t do it.

And yet, Mrs. O’Leary would have quibbled over “Yours faithfully.”

It kept Steven awake at night and left him staring vacantly into space in history and geography classes. His preoccupation reached its climax when he sat next to Lewis the whole of one breaktime without saying a word. After three attempts to engage Steven in conversation, Lewis called him a “tosser” and stalked off.

Steven knew he had to commit to one or the other.

It was only when he actually put pen to paper—using his neatest block capitals—that he suddenly had the brainwave of writing “Sincerely” instead of “Yours sincerely.” It solved every problem he’d had. He was sincere in his request, but he sure as hell wasn’t Yours.

Steven posted the short letter with high hopes.

Ten days later, he received a reply.

Chapter 8

“SCUM-SUCKING EGG AND TOMATO.” LEWIS GLARED AT HIS sandwich, then squinted up at Steven. “What you got?”

Steven leaned on his spade and wiped sweat off his face with his bare arm. He hesitated as if he might lie, but finally it was too much trouble.

“Peanut butter.”

“Peanut butter!” Lewis got up. “You want to swap?”

“Not really.”

Lewis knew he wouldn’t want to swap. Tomato made Steven sick. He knew that, and he knew Steven knew that he knew that, but the thought of peanut butter instead of egg and tomato made him selfish.

“Ah, bollocks; you can take it out. Half and half. Can’t say fairer than that.”

He was already rummaging in Steven’s Spar bag. Mr. Jacoby’s shop used to be Mr. Jacoby’s shop. Now it was a Spar and Mr. Jacoby had to wear a green Aertex shirt with an arrowhead logo on his ample bosom.

Steven looked helplessly at Lewis’s back.

“Don’t take the good half.”

He sighed inwardly. Having Lewis with him was a mixed blessing.

When he was on his own, Steven dug and dug and dug and ate his sandwiches and drank his water and dug some more. On a good Saturday he could dig five holes. Each was the length, depth, and breadth of an eleven- year-old boy, although Steven was not stupid enough to think that this gave him any advantage. He understood that