he’d have stood a similar chance of success if he had dug a series of two-foot-wide, four-foot-deep holes shaped like elephants. But he was looking for a body of a particular size and shape, and the holes he dug were a constant reminder of that. It was an exhausting and usually solitary pursuit, but a strangely satisfying one.

But when Lewis made his occasional forays onto the moor everything changed. Certainly, it was more companionable and there was less chance of the hoodies chasing him home, but there were drawbacks.

For a start, Lewis always arrived with the words “Want some help?” but no help was ever forthcoming. Lewis never brought his own spade or offered to relieve Steven of his.

What’s more, Lewis’s very presence—far from helping Steven—actually hindered him. Lewis talked and asked questions, which Steven felt compelled to answer. Lewis pointed things out too—things which Steven, with his head bent over the heather, would never have seen, much less cared about—and wanted to discuss them.

“Shit! Look at that!”

“What?”

“That. There!”

And Steven would have to look up and lean on his spade.

“What is it?”

“I don’t know. I think it was an eagle.”

“Buzzard, most like. There are tons of them around here.”

“What do you think I am? Some kind of moron? I know a buzzard and this wasn’t a buzzard.”

Steven would shrug and turn back to his hole. Lewis would sit and look around, or pick up the Ordnance Survey map with its blue biro crosses, denoting where Steven had dug, scattered like a constellation.

“This is a bad place to dig.”

“It’s as good as anywhere.”

“No, it’s not.” Long silence. “You know why?”

“Why?”

“You don’t think like a murderer.”

“Yeah?” Steven would wrestle with a knot of vegetation, grunting and twisting.

“Yeah. What you got to do, see, is think: If I murdered someone, where would I bury them?”

“But he buried them all between here and Dunkery Beacon.”

Lewis would be silent, but only for a moment.

“Maybe that’s where everybody’s gone wrong. See, if I killed six people and buried them here, maybe I’d start somewhere else after that. Over there. Or up at Blacklands. Reduce the chances of anyone finding them, see?”

Long silence.

“Steven? See?”

“Yeah. I see.”

“Next time I come up to help, I’m digging at Blacklands.”

The other thing that Lewis did was eat his sandwiches. Steven had tried lying about what was in them, but Lewis always checked and then ate them anyway. And then Steven would have to eat Lewis’s sandwiches immediately, whether he was hungry yet or not, otherwise Lewis would eat them too and he’d be left with nothing.

And Lewis got bored. Rare was the day when he did not start demanding that they go home by four o’clock, when there was still a good three hours’ digging to be done.

Steven couldn’t remember ever digging more than three holes while Lewis was with him. Even so, when Lewis said he was coming to help, Steven always encouraged him. Having his friend there made Steven feel less weird—as if digging up half of Exmoor for a corpse was quite normal, as long as one had a companion.

Now he threw down the spade and pulled the Spar bag open.

“You took the good half!”

“I didn’t!”

“You did! You took the half with the top crust!”

A look of astonished innocence passed over Lewis’s broad, freckled face. “You call that the good half? Sorry, mate.”

Steven sighed. What was the point? He and Lewis had discussed the good half of a sandwich on at least six occasions. Lewis knew the good half as well as he did, but in the face of such blatant denial, what could he do? Was the good half of a peanut butter sandwich worth losing a friend for?

Of course, Steven knew the answer was no—but he felt dimly that at some point in the future, the moment might come when all the bad-half sandwiches he’d had to swallow exploded out of him and washed Lewis away on an unstoppable tide of resentment.

He ate his own sandwich quickly, then picked the tomato out of the half of egg sandwich Lewis had left him —the bad half again, he noticed wearily—and ate that too.

Steven had not told Lewis about the letter. He was embarrassed by it, as if he’d written a letter to Steven Gerrard asking for an autograph.

Of course, if he had Steven Gerrard’s autograph, every boy in the school would have wanted to look and touch (except for Uncle Billy, the loser Man City fan, thought Steven fleetingly). But until such an autograph was granted, the author of that request would have had scorn—and possibly physical violence—poured onto him on a daily basis.

No, only if and when it ultimately yielded up the body of William Peters did anyone have to know about the letter.

Then Steven would admit what he had done, in the certain knowledge that Nan and Mum would agree—and be thankful for the fact—that the end had justified the means.

Steven’s initial thrill at receiving Arnold Avery’s letter was supplanted by disappointment when he read it. At first.

After a few days, however, the two neatly written sentences contained therein had begun to take on a deeper meaning in his mind. The very fact that—apart from Avery’s prison number along the top of the page—there were only two sentences required that they be pored over and analyzed in a way that a six-page rant never would have been.

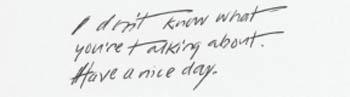

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.” After a couple of days, Steven decided that this was just not true. Could not be true! Contrary to Lewis’s assertion, Steven had done his very best to think like a murderer when writing the letter, and he had more knowledge of how murderers thought than most twelve-year-olds.

After the bedroom incident where he had pissed his pants (which, mercifully, neither he nor Lewis ever referred to), Mum had told him about what happened to Uncle Billy.

At first Steven had been numbed with horror but, with Lewis’s excited encouragement, he slowly learned to be fascinated. His mother had told him Avery’s name, but would say little else about him. Instead, over the next year or so, Steven had read about serial killers. He’d thought it best to do this in secret, hiding library books in his kit bag and reading under the sheets by torchlight.

With many nervous moments spent hearing footsteps creak towards him outside the protective duvet cocoon, he learned more about murder than any boy his age should ever know.

He learned of organized killers and disorganized killers; of thrill seekers and trophy takers; of those who stalked their prey and those who just pounced as the mood seized them. He read of crushed puppies and skinned cats; of bullies and bullied; of Peeping Toms and fire starters; of frenzied hacking and clinical dissection.

Steven’s manic reading had two major effects. First, in a single year his school-tested reading age leaped from seven years to twelve. Secondly, he learned that despite the seemingly crazy nature of their work, serial killers like Arnold Avery were in fact quite methodical. This told him that if he was true to type, Avery was likely to remember those he had killed quite vividly.

For a start, each of his victims had been chosen deliberately and, if Avery hadn’t known their names when he killed them, he sure took the trouble to find out afterwards.

In the fifteen minutes of free internet time he could devote to his search on any one day at the school library,