manuscripts, monuments, and artifacts streaming into his country as a result of Swedish victories on the battlefield.

Now, three hundred years later, the story of Rudbeck’s adventure appears in English for the first time. It is an epic quest that at every turn shows a bizarre combination of genius and madness. The book takes us back not only to the castles, courts, and peasant villages of the seventeenth century, but also to a world of

Yet it is much more than just a journey through a dreamy landscape. As I came to understand, this story has much to teach us about our own search for enlightenment. It dramatically illustrates how our greatest gifts of mind and spirit can become unexpected perils—and lead us to create our own spectacular monstrosities. At the same time, it is an inspirational tale that affirms the enormous potential for human achievement in the face of staggering obstacles. There is indeed much to learn from entering the strange world of Olof Rudbeck, the last of the Renaissance men and the first of the modern hunters for lost wisdom.

1

PROMISES

—ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE,

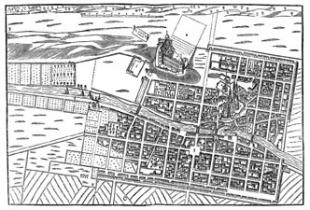

Uppsala University was at this time the jewel in the crown of the Swedish kingdom. Although the university had fallen into disuse a few years after its establishment in 1477, the state had realized its enormous potential as a training ground for the new Protestant Reformation and reopened it with royal flair. Young people came from all corners of the realm to learn the theology and acquire the intellectual rigor required to enter the Church. The university also attracted the scions of the great aristocratic houses, sons of the landed and titled families who waged Sweden’s wars, administered the empire, and served the Crown in countless other capacities. King Gustavus Adolphus, the famed “Lion of the North,” had envisioned just such a role for Uppsala University. He had endowed it with the means to realize it as well, even filling its empty bookshelves with many magnificent collections looted from an almost unbroken string of victories on the battlefield.

Rudbeck was neither a nobleman nor an aspirant to a career in the Church, though he was thrilled all the same to enter the halls of Scandinavia’s oldest university. This was understandably an exciting place for a young man. Despite repeated efforts of the authorities, students flocked to the taverns as much as to the lecture halls. Entertainment options ranged from dice to duels. It was already becoming common for students to carry swords, and sometimes even pistols. New brothels opened to meet the increasing demand, and other institutions emerged to serve the changing times, such as the university prison. Housed in the cellars of the main university building, the prison was rarely unoccupied.

Rudbeck’s interests, however, lay elsewhere. Ever since he was a boy, he had enjoyed finding his own way. He sang, he drew, he played the lute, he even made his own toys, including a wooden clock with a bell to strike the hour. Adventurous and independent, Rudbeck yearned to experience the world for himself. In fact, as a ten-year- old, Rudbeck had eagerly tried to follow his older brothers to Uppsala. His father, however, would not allow it, convinced that he was not mature enough to handle the freedom of the university.

Standing tall and giving the impression of no small confidence, Rudbeck was a spirited, highly impressionable youth with short dark hair, broad shoulders, and a barrel chest. He walked, or rather strode, with the air of someone who fearlessly plunged into his latest passion. His imagination, at this time, was fired by the study of anatomy. This was an especially attractive subject for bright, ambitious students. Kings and queens had showered favors on the talented few they chose as royal physicians, and indeed the newly established post of court physician had raised the status of the doctor from its previously undistinguished connotations. Enthusiasm for medicine as an intellectual pursuit peaked when an Englishman named William Harvey published a small Latin treatise in 1628.

Harvey was one of those elite court physicians, serving King James I of England. In his classic

It was in this climate that Olof Rudbeck entered the medical school at Uppsala. His head was full of ideas, his curiosity almost boundless. He could not wait to be turned loose to investigate for himself the mysterious invisible world underneath the skin. But unfortunately the university had very little to offer. Rudbeck’s supervisor was too busy for him, preferring instead to spend time in the alchemy lab, trying to change various substances into gold. More challenging still, it was difficult to gain access to the necessary equipment. When acquiring human bodies for observation and dissection was a difficult task even for a professor, what could a student do?

One crisp autumn day in 1650, Rudbeck strolled down to the market, a bustling square jammed with carts, stalls, and stands. There were stacks of cheese, slabs of butter, and fish, gutted and stretched out. Gloves of fine goat-hair and warm wolfskin coats also competed for attention. Rudbeck’s eye, however, fell on two women, rough and splattered with blood, as they butchered a calf. There, in the raw dead flesh, Rudbeck saw something peculiar. There was a milklike substance that seemed to emanate from somewhere in the chest, not so delicately split open on the old bench. His curiosity was piqued, and an idea suddenly struck him. With the enthusiasm of someone who had long enjoyed taking things apart and tinkering to see how they worked, Rudbeck asked if he could cut on the carcass.

The women must have been surprised, to say the least, at this young man’s request. With their permission granted, Rudbeck borrowed the knife, forced the thick, lifeless aorta to the side, and then separated it from the surrounding red mess of muscle and tissue. He followed that curious milk-like substance along, finding a sort of vessel or duct that carried a colorless liquid. By the time he traced it back to the liver, the dark purplish brown organ undoubtedly destined for dinner fare, he knew he was onto something big.

Rudbeck had discovered nothing less than the lymphatic system. The colorless liquid was lymph, a tissue- cleansing fluid vital to the functioning of the body’s immune system. Among other things, it absorbs nutrients, collects fats, and prevents harmful substances from entering the bloodstream. He not only discovered this system but also correctly explained its functions in the body.

This episode clearly shows a resourcefulness that would long be a hallmark of Rudbeck’s approach to problem-solving. As William Harvey improved his knowledge of anatomy by investigating the deer bagged by King James and the royal hunting parties, Rudbeck the student relied on the successful meat trade of Uppsala’s butchers. Over the next two years, probably working in a dingy makeshift shed by the river, Rudbeck set his dissection table with a veritable smorgasbord of discarded delicacies. He cut, nipped, hacked, and examined, performing hundreds of dissections and vivisections to refine his practical understanding of the body’s cleansing mechanisms.