Certainly army

Now, however, in 1827, two decades after Trafalgar, the pendulum of military fortune was swinging back: it was His Majesty’s ships that would again make war in the cause of peace and of liberty; the slave trade was being vigorously suppressed, and a triple alliance of Britain, France and Russia would oblige the Turks to quit Greek waters – the very cause for which Byron had died in the Peloponnese, and which philhellenes throughout Europe had long promoted. The Royal Navy was at last resurgent. Men like Matthew Hervey’s friend Captain Sir Laughton Peto, who had thought themselves beached, would have their chance once more.

But what of those in red coats? There were certainly far fewer of them than at any time in the life of all but the most grey-haired. Many were gaining a good dusting in far-flung corners of the growing empire; Hervey’s own uniform, though blue not red, had had a good dusting in India, and of late in the Cape Colony. But the growing use of the army to police the nation’s agrarian, industrial and political unrest made the cavalry unwelcome in some quarters (‘Peterloo’ was on the lips of many a rabble-rouser yet, and in the pages of the radical press). And when the explosive element of Catholic emancipation was added, coupled inextricably as it was with the condition of Ireland, society at times looked distinctly brittle. The old order was changing; the statesmen and soldiers who had brought Bonaparte to his knees and had managed to keep a lid on the unrest during the economic depression that followed were passing. New men gilded the ancient games.

This, then, is Matthew Hervey’s world, simple soldiering no longer his refuge. Family and friends are become equally a source of comfort and of disquiet. His future is on the one hand settled and propitious; on the other, uncertain and discouraging:

I

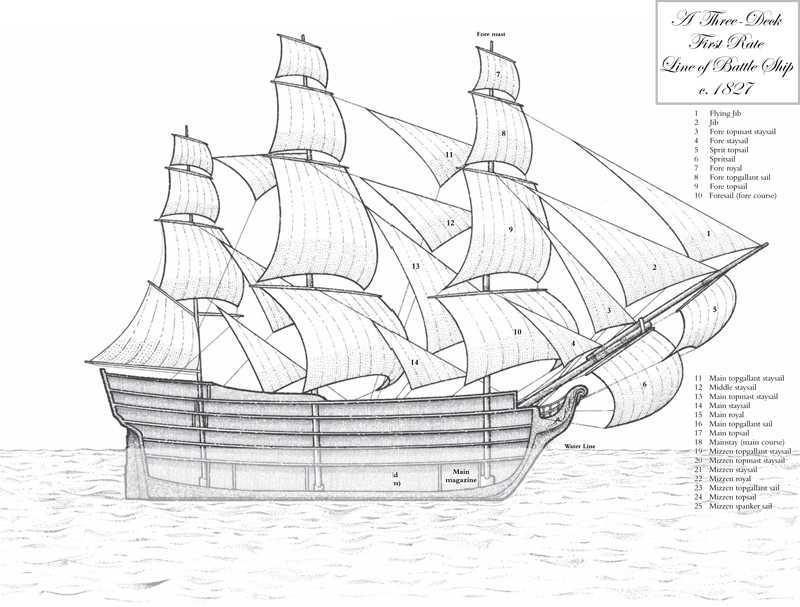

A FIRST-RATE COMMAND

The barge cut through the swell with scarcely a motion but headway – testament to the determination with which her crew was bending oars. In the stern sat Captain Sir Laughton Peto RN, his eyes fixed on their objective, His Majesty’s Ship

She was an arresting picture, to be sure, but neither did it do for a captain, especially one of his seniority, to have eyes for so mere a thing as a boat’s crew; his attention must be on more elevated affairs than a midshipman and a dozen ratings. Above all, though, it was opportunity to study his new command as an enemy might. Peto was acquainted by reputation with her sailing qualities, but how might another, impudent, man-of-war’s captain judge her capability? He fancied he might know what a Frenchman would think. That mattered not these days, however; it was what a Turk thought that counted, for a year ago the Duke of Wellington, on the instructions of the foreign secretary, Mr Canning, had signed a protocol in St Petersburg by which Russia, France and Great Britain would mediate in the Greeks’ struggle for independence; and increasingly that protocol looked like a declaration of war on the Ottoman Turks.

What a mazy business it all was too: the prime minister, Lord Liverpool, on his sickbed for months, and in April the King sending for Canning to form a government, in which many including the ‘Iron Duke’ then refused to serve; and now Canning himself dead and the feeble Goderich in his place. Peto did not envy Admiral Codrington, the commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean, whose squadron he was to join: how might the admiral do the government’s will in Greek waters when the government itself scarcely knew what was its will? He could not carp, however, for he was the beneficiary of that uncertainty: soon after

The wind was strengthening. Peto did not have to take his eyes off his ship to perceive it. Nor did he need to crane his neck to mark the frigate-bird that accompanied them, tempting a prospect though such an infrequent visitor was – and sure weather vane too, for he had frequently observed how the bird preceded changeable weather, as if borne by some herald of new air. With a freshening westerly it would not be long before