Peter Matthiessen

Killing Mister Watson

The first book in the Watson trilogy series, 1990

TO THE PIONEER FAMILIES OF SOUTHWEST FLORIDA

In a six-year search, I have had great help from at least one member of almost every family mentioned, and am grateful to dozens of native Floridians for their time and courtesy and help, including a few who have not survived to see the finished book-the late Ruth Ellen [1] Watson, Rob Storter, Robert Smallwood, Sammie Hamilton, and Beatrice Bronson, three of whom offered childhood memories of Mister Watson.

Special gratitude is due to Larry (Watson) Owen, who made a great variety of contributions; also to Mary Ruth Hamilton Clark and Ernie House. My sincere thanks to Frank and Gladys (Wiggins) Daniels, Marguerite (Smallwood) and Fred Williams, Nancy (Smallwood) and A. C. (Boggess) Hancock, Bert (McKinney) and Julia (Thompson) Brown, Loren 'Totch' Brown, Bill and Rosa (Thompson) Brown, Louise Bass, Paul Duke, Doris Gandees, Preston Sawyer, Buddy Roberts, Edith (Noble) Hamilton.

I am also indebted to the researches, writings, and good counsel of the historian Dr. Charlton W. Tebeau, author of

None of these friends and informants are responsible for my interpretations of their accounts of the life and times of their own families and others, for all of which I accept full responsibility.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

A man still known in his community as E.J. Watson has been reimagined from the few hard 'facts'-census and marriage records, dates on gravestones, and the like. All the rest of the popular record is a mix of rumor, gossip, tale, and legend that has evolved over eight decades into myth.

This book reflects my own instincts and intuitions about Mister Watson. It is fiction, and the great majority of the episodes and accounts are my own creation. The book is in no way 'historical,' since almost nothing here is history. On the other hand, there is nothing that could not have happened-nothing inconsistent, that is, with the very little that is actually on record. It is my hope and strong belief that this reimagined life contains much more of the

PROLOGUE: OCTOBER 24, 1910

Sea birds are aloft again, a tattered few. The white terns look dirtied in the somber light and they fly stiffly, feeling out an element they no longer trust. Unable to locate the storm-lost minnows, they wander the thick waters with sad muted cries, hunting signs and seamarks that might return them to the order of the world.

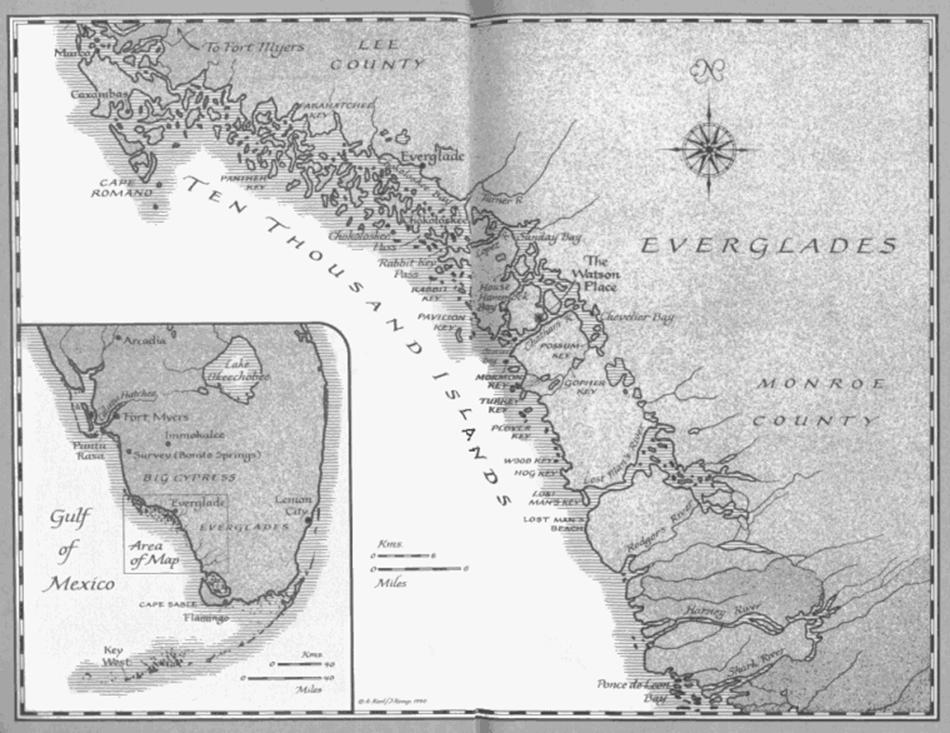

In the hurricane's wake, the labyrinthine coast where the Everglades deltas meet the Gulf of Mexico lies broken, stunned, flattened to mud by the wild tread of God. Day after day, a gray and brooding wind nags at the mangroves, hurrying the unruly tides that hunt through the broken islands and twist far back into the creeks, leaving behind brown spume and matted salt grass, driftwood. On the bay shores and down the coastal rivers, a far gray sun picks up dead glints from windrows of rotted mullet, heaped a foot high.

From the island settlement on the old Indian mound called Chokoloskee, a baleful and uneasy sky out toward the Gulf looks ragged as a ghost, unsettled, wandering. The sky is low, withholding rain, and vultures on black- fingered wings tilt back and forth over the broken trees. At the channel edge, where docks and pilings, stove-in boats, uprooted shacks litter the shore, odd pieces torn away from their old places have been strained from the flood by the limbs over the water. A clothesline flutters in the trees; thatched roofs are spun onto their poles like old straw brooms; frame buildings sag. In the dank air a sharp fish stink is infused with corruption of dead animals and blackened vegetables, of excrement in overflowing pits from which shack privies have been washed away. Pots, kettles, crockery, a butter churn, tin tubs, buckets, salt-slimed boots, soaked horsehair mattresses, and ravished dolls are strewn across the pale killed ground.

A lone gull picks disconsolate at the softening mullet along shore, a dog barks without heart at so much silence.

A figure in mud-fringed calico, calling a child, stoops to retrieve a Bible, then wipes wet grime from the Good Book with pale dulled fingers. She straightens, turning slowly, staring toward the south. From the wall of mangroves far off down the bay, the drum of the boat engine comes and goes, then comes again, a little louder.

'Oh, Lord,' she whispers, half-aloud. 'Oh no, please no, sweet Jesus.'

Along toward low gray-yellow twilight, Postmaster Smallwood, on his knees beneath his store, is raking out the last of his drowned chickens. What the hurricane has left of Smallwood's dock-a few poor pilings-sticks out at angles off the end of the spoil bank where he'd dug his canal for Indian canoes. From there the pewter water spreads away to the black walls of mangrove on all sides.

He crouches in the putrid heat. Voices are whispering, as at a funeral. One pair of bare feet, then another, pass in silence on the way down to the landing. He knows his neighbors by their gait and britches. Over the whispering, over short breaths, comes the drumming of the motor, softened by distance, east through Rabbit Key Pass from the Gulf of Mexico. In a shift of wind, the

Three days before, when that boat had headed south, all ten families on the island watched it go. Smallwood was the only man to wave, but he, too, prayed that this would be the end of it, that the broad figure at the helm, sinking into darkness at the far low line of trees, would disappear forever from their lives. Said Old Man D.D. House, 'He will be back.' The House clan lives one hundred yards away, east of the store. Ted Smallwood sees his father- in-law's black Sunday boots descend the Indian mound, with Bill House and Young Dan and Lloyd barefoot behind. Calling his sister, Bill climbs the porch and enters the store and post office, which has the Smallwood family rooms upstairs. Feet creak on the pine floor overhead.

In the steaming heat, in the onset of malaria, Smallwood feels so sickly weak that when his rump emerges and he tries to stand, blood thumps his temples and the trees go black. He is a big man and bangs heavily against the wall of his frame house, causing his wife, somewhere inside, to cry out in alarm. Slowly he straightens, arches his stiff back. He takes a deep and dreadful breath, gags, coughs, and shudders. He hawks the sweet taste of chicken rot from his mouth and nostrils.

'Look what come crawling out! Ain't that the postmaster?'

The postmaster's spade, jammed at the black earth by way of answer, grates on old white oyster shells of the huge midden. Again he jams it, and it glances off a root. The House boys laugh.

'Keep that spade handy, boy. Might gone to need it.'

Ted Smallwood says, 'Got four rifles there, I see. Think that's enough?'