Dazai Osamu

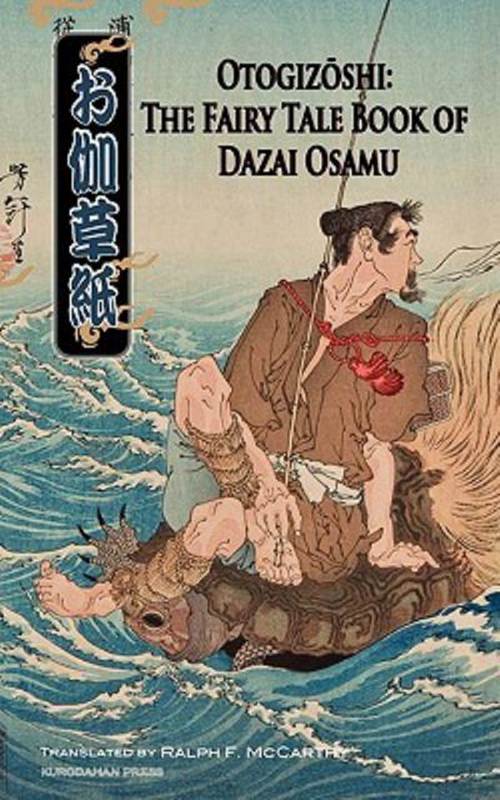

Otogizoshi: The Fairy Tale Book of Dazai Osamu

Translated by Ralph F. McCarthy

Introduction

Joel Cohn

The air raids that devastated most of the large and medium-sized cities of Japan in the final year of World War II form a decidedly unconventional backdrop for Dazai Osamu’s retellings of four well-known Japanese folk tales. As Dazai’s prologue indicates, he composed these stories in the spring and early summer of 1945 as the increasingly frequent air raids, which had begun in November of 1944, were adding an element of more or less constant danger to the already difficult lives of the residents of Tokyo and other Japanese cities, many of whom had nothing more to rely on in the way of protection than hastily dug backyard trenches. After evacuating his wife and two young children

In the less than three years that remained before the drowned bodies of Dazai and a mistress were discovered, apparently in the aftermath of a double suicide, he burst forth from relative obscurity to become the first great literary sensation of postwar Japan. His best-known works from these years, especially the novels

To many, including some who have never actually read anything by him, Dazai is a virtual poster boy for the stereotype of the modern Japanese novelist as a tormented spirit, a suicide waiting to happen, and the mere mention of the titles of his best-known works is enough to evoke images of all-encompassing despair. But even at its grimmest, his writing is regularly illuminated with flashes of sardonic wit, and in much of it, especially the pieces from the middle years of his relatively brief career, the sense of angst is muted and his penchant for subtle comedy is deftly displayed.

Turning to traditional Japanese materials was an attractive option for writers during the war years, as they afforded a source of relatively safe subject matter and met the government-imposed mandate for writing that conformed to “national policy” as long as they were handled with proper respect. Dazai had already produced a number of pieces in this vein, but he was rarely one for playing along with authority figures of any kind. In

As some of these comments suggest, Dazai was also a writer with a compulsive urge to reflect, or even project, his real-life experiences and concerns in his work. In other words, he was very much a representative of the predilection for autobiographical or self-referential semi-fiction, known as

For Japanese readers this addition of a new angle to long-familiar stories is likely to provide a large part of the fun. But for many of them, the pleasure of reading Dazai is as much about getting a feeling of being in touch with the author as it is about being drawn into the world of a story, and in these tales Dazai’s distinctive voice is very much in evidence, reaching out and taking us into his confidence in a warm, intimate tone. Far more often than a conventional storyteller might, he persistently provides his own running commentary on the main events of the tales-sometimes trying to extract a meaning, sometimes wandering off on a tangent that relates more to his own preoccupations than it does to any events in the story. We may not know, or care, whether the “real Dazai” indeed lived through moments like those he describes here, or whether he actually believed everything the storyteller claims to believe, but as in the tales that were told to us as children, the voice and presence of the teller, by turns reassuring, fearsome, and clownish, and occasionally wise, is as much a part of the experience as the incidents and characters themselves.

This is not the only way in which Dazai transforms the traditional tales. He fleshes out the bare bones characterizations and situations of the children’s storybook versions (shown in the translation in bold type), giving each of the sketchily described stock figures of the originals a context and a distinctive personality. Most of these have little or no relation to the traditional story line, and some, such as the garrulous, wisecracking tortoise of “Urashima-san” and the disastrously gendered tanuki and rabbit of “Click-Clack Mountain,” are truly memorable. Many of them are endowed with a degree of psychological complexity and ambiguity that owes more to the techniques of modern fiction than to the simplistic good or evil characterizations of conventional folk tales; this is particularly apparent in the final story, “The Sparrow Who Lost Her Tongue,” where the strengths and flaws of the husband and wife are depicted with deep sensitivity and understanding.

Dazai’s retellings also introduce a number of themes that play little or no part in the originals. Some of these will be familiar to readers who know other works of his: the quandary of the outsider who is taken seriously by nobody and misunderstood by everybody, including himself; the family and male-female ties, including marriage, that become emotional dead ends rather than sources of comfort or fulfillment; and the suspicion that things are all too likely to go wrong when people are left to their devices,