Stewart Binns

LIONHEART

MAP I

England in the Twelfth Century

MAP II

Europe in the Twelfth Century

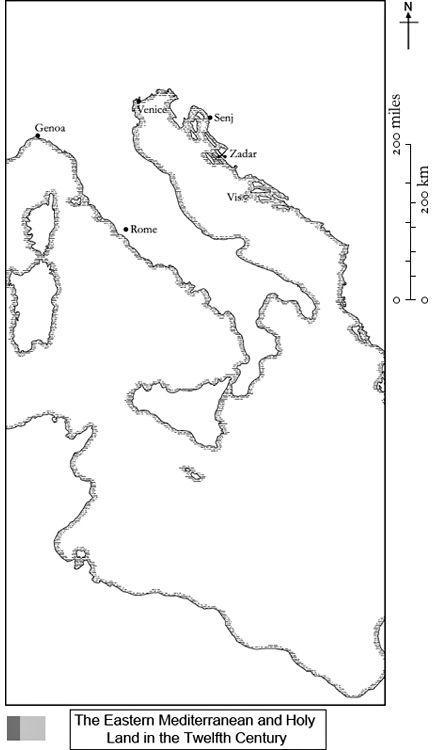

MAP III

The Eastern Mediterranean and Holy Land in the Twelfth Century

MAP IV

The Routes to the Third Crusade

MAP V

The Holy Land during the Third Crusade

Towards the end of the reign of Henry II, the Plantagenet Empire stretched across a huge swathe of north-west Europe. The Scots had declared their fealty to Westminster, and Ireland and Wales both acknowledged the English King as their liege lord. Across the Channel, all French domains – save those of the King of the Franks, in Paris, and the Count of Toulouse – were part of a vast realm that stretched from the north of Scotland to the Pyrenees.

Like his father before him, and his Norman predecessors before that, Henry was all-powerful, especially when allied with his remarkable wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Fortunately, their lineage included sufficient sprinklings of the blood of their diverse subjects, including the English, to keep any adversaries at bay. However, Henry and Eleanor produced eight offspring who were so formidable they were soon called the ‘Devil’s Brood’. They included two future queens and two kings, but the most remarkable of all was the sixth child, Richard, Duke of Aquitaine, who would be called ‘Lionheart’ before the age of twenty – and fifteen years before he would become King of England.

His physical presence, his domineering personality and his remarkable military prowess – not only as a general of armies but also in hand-to-hand combat – made him a legend in his own lifetime. His struggles during the Third Crusade against the Sultan Saladin (himself one of the most revered men in Muslim history) soon became one of the most compelling stories of the Middle Ages.

But there was more to Richard’s lineage than he realized. When he became King of England on 6 July 1189, there were two men with him who had been charged with protecting the young King and guiding his future. One of them was a knight of the realm, chosen for his martial skills and personal integrity, and the other was a monk, a wise man of letters, who carried vital clues about Richard’s past – evidence that would shape his future and that of England. This is their story.

1. Old Man

When I first saw the old man, it was as if I was looking at an apparition, a venerated image held in my memory since childhood.

As a boy, I had been told the stories about England’s ancient heroes many times: the great King Harold and his mighty housecarls, who fought to the death at Senlac Ridge in a valiant attempt to defeat the Conqueror’s Norman army; the gallant defenders of the Siege of Ely, the last of the brave souls who had defied Norman rule; and the most courageous of them all, Hereward of Bourne, the leader of England’s final rebellion, about whom people still spoke with hushed reverence.

These men of legend wore their hair and beards long, carried the round shields of Saxon tradition and went into battle wielding their fearsome battleaxes. But they were from another time, a distant memory. Senlac Ridge had happened over a hundred years ago, and even though there were a few old men alive who claimed that their grandfathers could remember Hereward and the early days of the Conquest, no one really believed them.

Now everyone trimmed their hair and beards like our Norman masters. We wore Norman clothes, with their elaborate embroidery and rich colours, and we carried Norman weapons and armour. To all intents and purposes, we

But the old man in front of me did not resemble a Norman. Apart from his age – he must have been well into his seventies – he was the epitome of the English heroes of the past. Of a winter’s eve, when I had sat by the